Research By: Mark Lechtik and Raman Ladutska

The Brazilian cyberspace is known to be a whole ecosystem of its own and, although the banking malware that originates there has traditionally been somewhat basic, recent trends have indicated new and more refined tools for attack. Subsequently, what originally started in Brazil may well be about to spread to users of online banking worldwide.

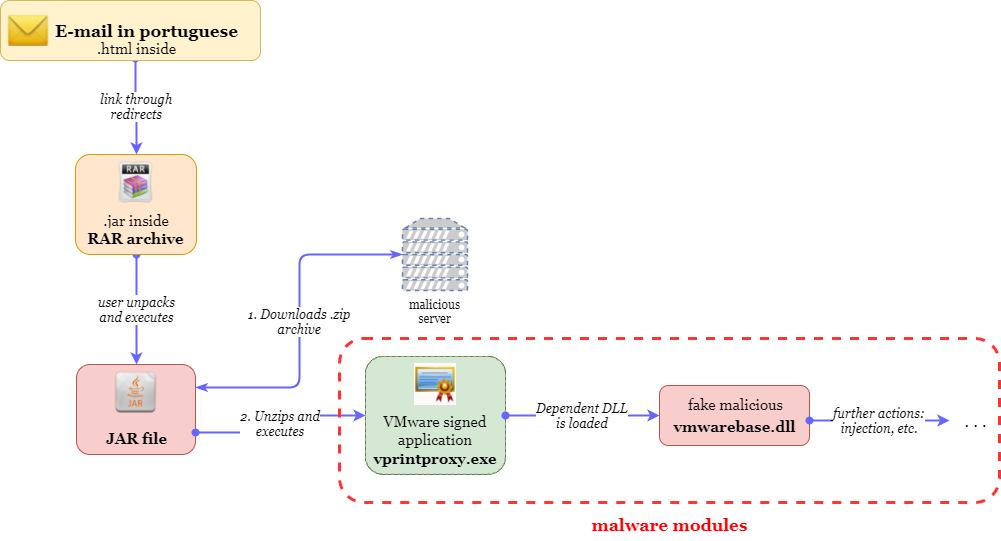

In May 2017, researchers at Talos analyzed a banking Trojan that was delivered in Portuguese via a spam campaign, a common delivery method for such malware. Upon opening the email attachment, victims would be redirected to a JAR file which executes a malicious JAVA code to initiate the malware installation process.

Until now, the deeper inner workings of this malware have remained locked due to the highly complex nature of the ‘Themida’ packing file. Thanks to the Check Point Research team however, we have been able to unlock this packer and can now reveal how this new variation of malware interacts with its victims.

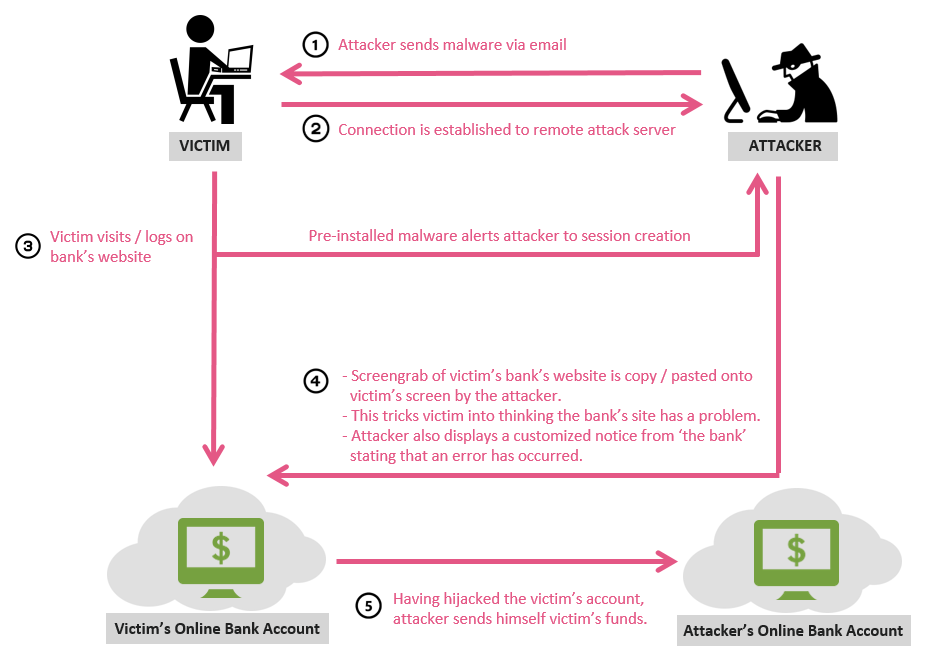

Our research below illustrates how a victim, once logged onto their online bank account, whether it be HSBC, Santander, Citibank or one of several Brazilian banks, is deceived into allowing the attacker free reign of their account. As a result of the attack, their account’s funds are then directly stolen without them even being aware.

In addition, through our research, we have been able to connect Talos’s work to that done by Trusteer who investigated a similar version of this malware back in January. Only now is it clear how these Brazilian banking malwares are connected and operate.

Banking malware enables the theft of millions of dollars each year from unsuspecting victims. By understanding more about how this particular attack operates and how it is perceived on the front end from the customer’s point of view, we hope to raise awareness and thwart similar attacks in the future.

How it Works

Research Analysis

Deploying malware on user machine

The scheme below describes the malicious code execution flow.

The executable used by the malware, named vprintproxy.exe (delivered under the name vm.png) is a legitimate file signed by VMware.

In order to conceal itself from security products, the malware uses a DLL hijacking technique in which the actual malicious code is stored in vmwarebase.dll, which is automatically being loaded by the legitimate VMware process once executed.

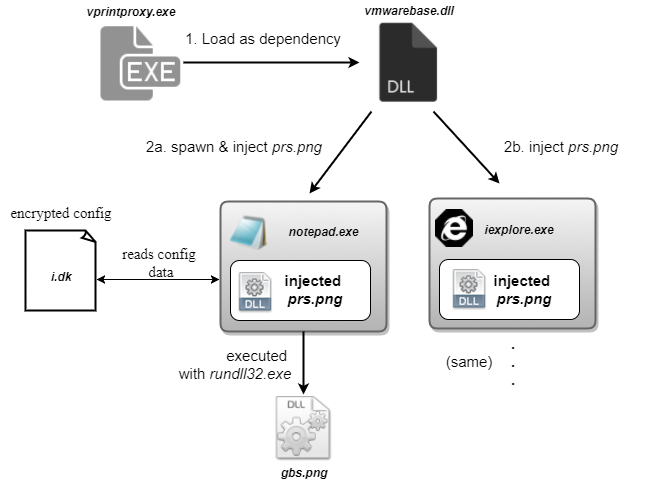

The malware modules are interconnected with each another as shown in the diagram below:

| Name in archive from server | Renamed when extracted from archive | Type | Main purpose |

| vm.png | [random].exe | EXE | Loads malicious dependent vmwarebase.dll |

| vmwarebase.dll | vmwarebase.dll | DLL | Injects prs.png into explorer.exe and notepad.exe |

| prs.png | [random].db | DLL | |

| gbs.png | [random].drv | DLL | Shows bitmap to lock the screen |

| i.dk | i.dk | TXT | Provides malware with C&C addresses |

Malware Technical Details

The following is a technical description of each of the main malware modules.

vmwarebase.dll – dropper

Once vprintproxy.exe is invoked and vmwarebase.dll is loaded as a dependency, execution is passed to its DllMain entry point. The sole purpose of this DLL is to inject prs.png (the core malware module) to both explorer.exe and to a spawned notepad.exe process. This is achieved using a simple DLL injection technique whereby the following actions take place:

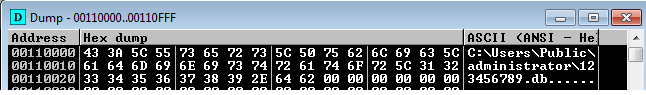

- The path of png (which has its name modified to a random integer between 0 and 999999999 and extension changed to db) is first resolved, by checking the specified random integer within the contents of C:\Users\public\Administrator\car.dat (delivered as part of the infection chain).

- Then the corresponding file is searched for in the C:\Users\public\Administrator If found, the path string would be simply written into an allocated buffer within the target processes, as appears in the image below:

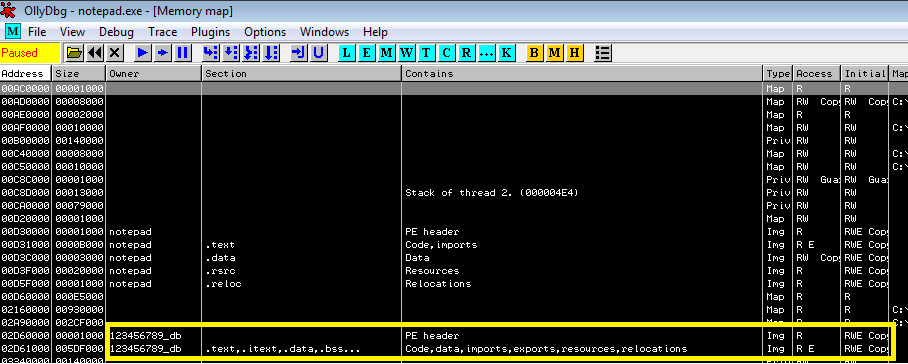

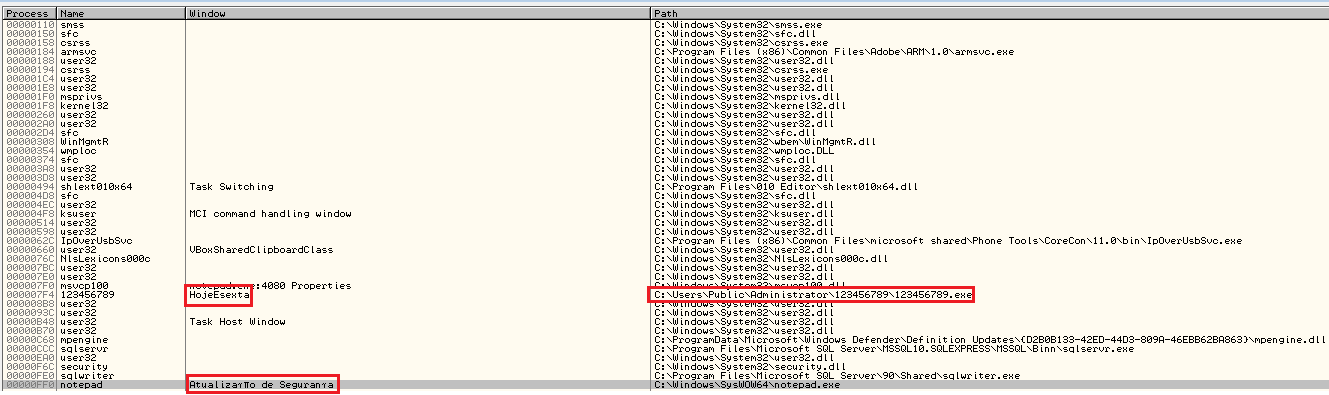

- The obtained path will be used as an argument to LoadLibrary. The latter would be resolved in the injecting process, and will be assumed to have the same address in the target process. Thus, LoadLibrary can be simply invoked with the aforementioned argument using CreateRemoteThread, causing the target process to load the malicious DLL into its address space. The resulting injected image can be seen below:

Before conducting the injection, vmwarebase.dll will enumerate all processes and will look for all running instances of conhost.exe. These will be closed, presumably to shut down windows from any previous stages of the infection chain.prs.png – 1st stage injected payloadThis module includes the following capabilities.

Before conducting the injection, vmwarebase.dll will enumerate all processes and will look for all running instances of conhost.exe. These will be closed, presumably to shut down windows from any previous stages of the infection chain.prs.png – 1st stage injected payloadThis module includes the following capabilities.

- Keylogger

- Screenshots

- Replacing current screen with a provided image

- Changing current system cursor

- Autorun registry persistence establishment

- Shutting down system utilities (such as taskmgr, dwm, regedit etc.)

- Invoking system reboot

- File\dir deletion functions

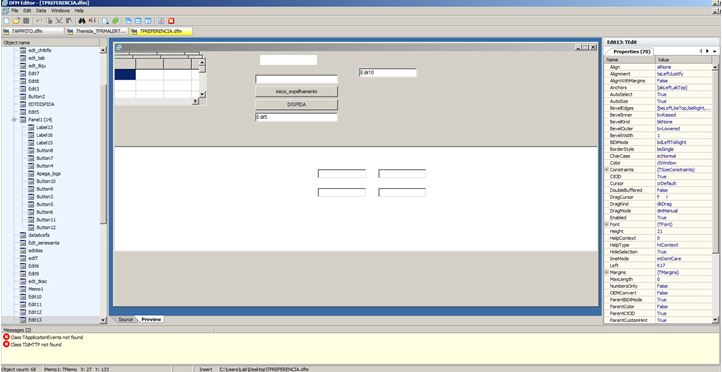

This malware has an interesting method of executing its malicious code. Most of the malware’s code as well its data is stored within forms embedded into this module.

Once executed the main form shows up on screen as a very small window, almost invisible. When resizing it to bigger dimensions, it looks like this:

These forms are essentially Delphi objects that contain various attributes such as Edit, Memo and other GUI components which are utilized for the purpose of storing important information.

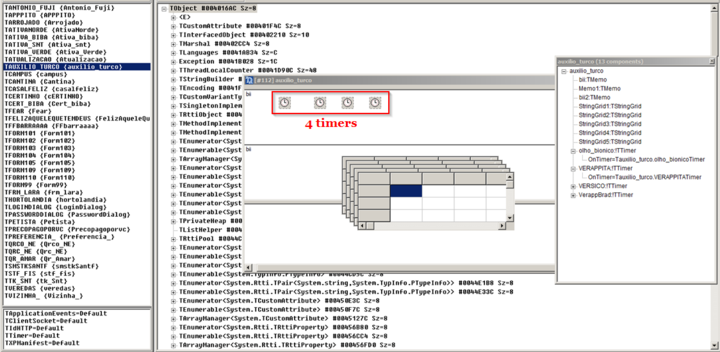

Multi-threading functionality is performed with the help of Timer objects, which are widely present across the forms. As an example, we can see the “TAUXILIO_TURCO” form, which contains various pieces of information and functionality as depicted below:

Killing unwanted applications:

Under certain circumstances this module will kill several applications, such as

- taskmgr.exe

- msconfig.exe

- regedit.exe

- ccleaner.exe / ccleaner64.exe

- dwm.exe (for Windows 7 only)

- iexplore.exe

- firefox.exe

- chrome.exe

- opera.exe

- safari.exe

- NetExpress50.exe

- AplicativoBradesco.exe

- itauaplicativo.exe

- office.exe

- javaw.exe

This module is responsible for C&C communication. In order to communicate with the C&C server the malware uses an AES-256 encrypted configuration section stored in a file name `i.dk`.

After decryption the configuration section looks like this:

Using phishing bitmaps to grab user’s sensitive info:

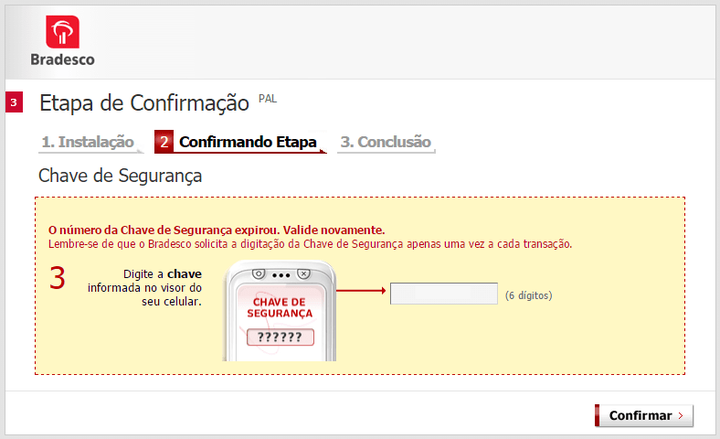

Some of the embedded forms contain multiple bitmaps. These are used to trick the user into entering his two-factor authentication number, which is a common practice by Brazilian banks and used by many of its users. Additionally, there are bitmaps which mimic an installation of a security component related to the banking site visited by the user. These will be shown on screen in the event that the attacker wishes to carry out actions from the victim’s browser (i.e. conducting a transaction directly from his account on the site), in which case the bitmaps are used to alert the victim that an ongoing action is taking place and he should refrain from doing anything on the computer. At the same time, the attacker is able to control the browser window and do any fraudulent activity, without the user’s awareness of this. The following are examples of the deceptive bitmaps extracted from the module:

gbs.png –2nd stage executed payload

This module is packed using a Themida packer and once executed is responsible for several actions described below:

Process termination protection

This technique is used to prevent terminating the malware process via task manager and is described further here:

Removing previously installed hooks

This malware module calls UnhookWindowsHookEx in a loop with arguments ranging from 1 to 5000, in an attempt to uninstall windows hooks that may have been set-up beforehand.

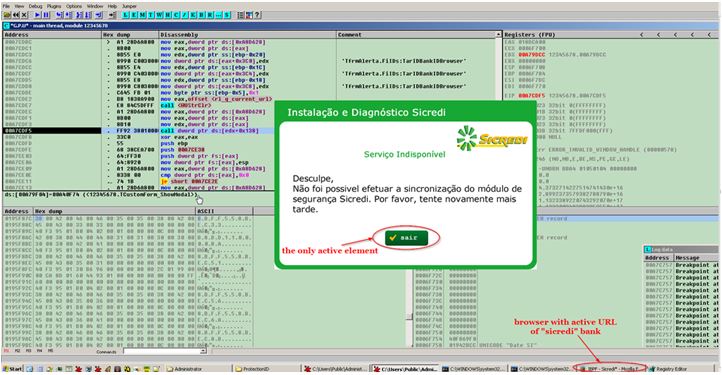

The primary functionality observed within this module is one responsible for displaying an overlay message to the user. This message (stating an alleged security error in the connection) is chosen amongst a number of hardcoded ones, and will correspond to the bank site visited by the user.

In a nutshell, the underlying mechanism involves a constant monitoring of the active URL inside the user’s open web browsers, which once found to be matching one of the “supported” bank websites (after authentication) allows the malware to choose a correlating fake overlay message and present it on screen.

This procedure is comprised of the following stages:

- URL monitoring in active browsers – the malware searches for all the windows in the OS using the combination of FindWindowW/GetWindow(…, GW_HWNDNEXT). When a browser related window is found, it’s active URL bar is inspected. For each of the enumerated browsers (Chrome, Firefox and Internet Explorer), a different method is used to capture the required URL.

- The obtained URL is checked against a hardcoded list of URLs presented below:

- aapj.bb.com.br/aapj/loginmpe

- www.santandernetibe.com.br/

- www.ib2.bradesco.com.br/ibpflogin/identificacao.jsf

- ww7.banrisul.com.br/brb/link/brbwe4hw.aspx?

- wwws5.hsbc.com.br/ITE/connect2/wcm_connect/pws/hsbc-online-cnb.html

- internetbanking.caixa.gov.br/SIIBC

- .bancobrasil.com.br/aapf/

- www.santanderempresarial.com.br

- aapj.bb.com.br/aapj/

- www.santandernet.com.br

- www.brasil.citibank.com/BRCIB/JPS/portal/Index.do

- internet.sicreditotal.com.br/stiapp/

- ibpf.sicredi.com.br

- wwws3.hsbc.com.br/ITE/common/html/hsbc-online.shtml

- ib.sicoobnet.com.br/inetbank/login.jsp

- itau.com.br/GRIPNET/bklcom.dll

- www.ib2.bradesco.com.br/ibpftelainicial/home.jsf

- www.citibank.com.br/BRGCB/JPS/portal/Index.do

- www.ne2.bradesconetempresa.b.br/ibpjlogin/login.jsf

- ww8.banrisul.com.br/brb/link/brbwe4hw.aspx?

3. Registry date check based on located URL – a registry path of the form: HKCU\Software\Trilian\[A-Z]{2} (where the last two letters are set based on the active URL found in browser) is checked to obtain a date value from one of it’s keys, which is then compared to the current system date. 3 outcomes are possible following this check:

a.Registry path or date value not found – carry out some finalizing code, and terminate.

b. System date is equal to or newer than the registry value date – the malware module deletes the keys “Block [A-Z]{2}” and “Date [A-Z]{2}” from the aforementioned registery branch and in turn searches for the key ProxyServer under HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings. If it’s value is set to 123.123.123.123:3212 then the key’s value is erased, and a new key named ProxyEnable is created, having it’s value set to 0. Following this, the browser with the obtained URL is killed and the monitoring loop is started all over.

c. System date is older than registry value date- the malware module sets a keyboard hook to intercept pressed service keys (e.g. WIN, ESC etc.).

4. Finally, the module pops a transparent modal form in full-screen (which can’t be closed by the user because of a keyboard hook), presenting him with a screenshot of the current active browser open. On top of this, one of 10 bitmaps (corresponding to the active bank site) is loaded and set in the center of the screen to prevent the user from any kind of activity. The only active element is a button for closing the form. Following is an example of a bitmap corresponding to sicredi.com.br:

Each of these bitmaps state something along the lines: “Sorry, it was not possible to synchronize with the security module of [bank name]. Please try again later.” This forces the user to close the form, which subsequently kills the browser. At the same time, the user will be presented with another overlay, pretending to install a bogus security component related to the visited site. Alongside, it will prompt the user for banking credentials or a possible 2FA security token.

Each of these bitmaps state something along the lines: “Sorry, it was not possible to synchronize with the security module of [bank name]. Please try again later.” This forces the user to close the form, which subsequently kills the browser. At the same time, the user will be presented with another overlay, pretending to install a bogus security component related to the visited site. Alongside, it will prompt the user for banking credentials or a possible 2FA security token.

Optional actions

If the active URL is empty then this module is capable of restoring the first 6 bytes of the following functions (in the event they were hooked or if breakpoints were set within their memory region):

- FindWindowExW

- FindWindowW

- SendMessageW

Following this, the monitoring loop will reiterate and start the above described procedure from the beginning.