Research By: Eyal Itkin

As part of our efforts in identifying vulnerabilities in different products, from time to time we also review the Linux Kernel, mainly searching for vulnerabilities in different drivers. In this case, we took a look into drivers trying to roll their own usage of the mmap() function.

The idea of re-implementing kernel functions is likely to lead to mistakes due to the fact that less QA staff in organizations review their code and fix security issues as part of their process. In this case we discovered and disclosed several problems and the specific bug we found is actually an eight-year-old vulnerability in a driver that can be used for escalating priveleges in the latest kernel version (4.16-rc3). Below is one example of such vulnerabilities.

MMAP Handlers

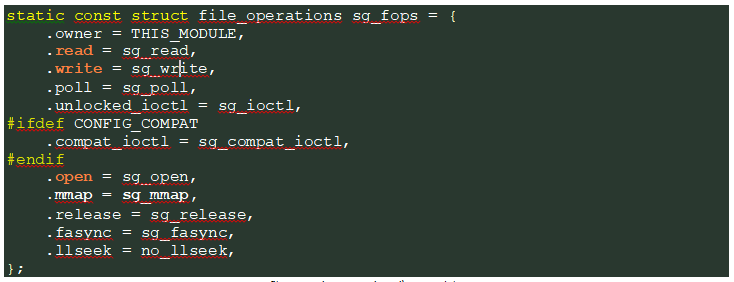

It’s not uncommon for drivers to implement their own version of file operation functions; this could be identified in the file_operations struct of a driver:

file_operations struct in scsi\sg.c module.

After searching for more information about these types of file operations, we found this very useful guide from MWR Labs: Kernel Driver mmap Handler Exploitation. While the guide explains in detail how an mmap() handler should be used, it also highlights common vulnerabilities in such drivers, including lack of input validations and Integer-Overflows. Equipped with this new information, we decided to search for possible vulnerable mmap() handlers in the entire kernel.

Before starting the search, it will serve us well to define what we were actually looking for. A classic driver should probably look like this:

- The driver will hold an internal buffer that represents the shared memory region with the peripheral device.

- The driver should only let the user access memory ranges that fall inside this buffer.

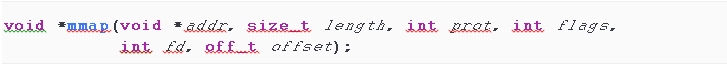

Now let’s look again at the prototype of the mmap() function from user-space (taken from man):

As we can see, there are plenty of fields an attacker can control and so a developer should perform the following checks, while trying to avoid possible Integer-Overflows, in order to avoid the pitfalls:

- Region start: 0 <= offset < buffer’s end

- Region end: buffer’s start <= offset + length <= buffer’s end

- Region start <= Region End

In actual fact, the last check can be spared since the Linux kernel will sanitize the supplied length, making it practically impossible to pass the first two checks while still passing the third check.

Now that we know how to spot a possible vulnerability, we need to find out where these vulnerabilities could be found. The guide states that the important function is remap_pfn_range() since this function will map physical memory pages to the user.

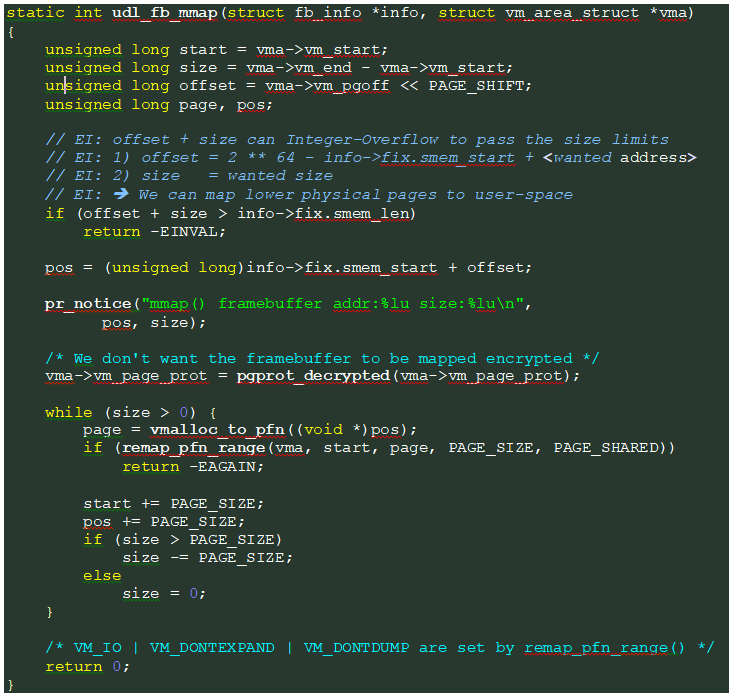

Using the naïve approach let’s just GREP for “remap_pfn_range(“ and see what we find. While trying to sort out the initial 158 results, we could get a good feel about the checks a common driver would do, making it easier to spot possible vulnerable candidates. After the list was narrowed down to six possible candidates, a deeper look showed a promising candidate:

- drivers\gpu\drm\udl\udl_fb.c – udl_fb_mmap()

DisplayLink Driver – CVE 2018-8781

The video/drm module in the kernel defines a default mmap() wrapper that calls that real mmap() handler defined by the specific driver. In our case the vulnerability is in the internal mmap() defined in the fb_helper file operations of the “udl” driver of “DisplayLink”.

Explanation: This is a classic example for an Integer-Overflow. Since offset is unsigned the programmer skipped check #1 and went directly to check #2. However, the calculation “offset + size” could wrap-around to a low value, allowing us to bypass the check while still using an illegal “offset” value.

Note: on 64 bit machines there are only 48 bits of accessible memory, meaning that if we use a huge “offset” to bypass this check we will also have to make sure that “info->fix.smem_start + offset” will wrap-around to a valid mapable physical address.

Demonstration

In order to verify the vulnerability, we used an Ubuntu 64-bit virtual machine, and uploaded a simulated vulnerable driver. On every test the driver’s mmap() handler contained the implementation that we wanted to check.

The user-mode code preformed 2 consecutive calls to mmap() on the vulnerable driver:

- length = 0x1000, offset = 0x0 -> sanity check

- length = 0x1000, offset = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF – 0x1000 + 1 -> vulnerability check

When setting the buffer’s address at the page-aligned physical address of the kernel’s /dev/urandom implementation, the output (on both cases) was the expected result:

- The correct physical page: 0x1531000

- The previous physical page: 0x1530000

Additional checks showed that the user can read and write from/to the mapped pages, giving an attacker a powerful primitive that could be used to trigger code execution in kernel space.

Disclosure Timeline

- 18 March 2018 – Vulnerability was disclosed to the Linux Kernel.

- 18 March 2018 – Linux issued a patch and asked for us to verify it.

- 18 March 2018 – We verified the patch and gave a “Green light” to continue.

- 21 March 2018 – An official Linux patch was issued for CVE 2018-8781.

- 21 March 2018 – The patch was integrated to the Linux Kernel.

Conclusion

The vulnerability allows a local user with access to a vulnerable privileged driver, to read from and write to sensitive kernel memory, causing a local privilege escalation. While the vulnerability was found using a simple search, it was introduced to the kernel eight years ago. This fact can teach us that even on a popular open source project as the Linux Kernel, you could always hope to find vulnerabilities if you know where to search.

References:

- MWR Labs Mmap Exploitation Guide: https://labs.mwrinfosecurity.com/assets/BlogFiles/mwri-mmap-exploitation-whitepaper-2017-09-18.pdf

- CVE 2018-8781 patch: https://patchwork.freedesktop.org/patch/211845/

- NVD – https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2018-8781