May 1, 2018

Research By: Mark Lechtik and Michael Kajiloti

Revealed: In an exclusive piece of research, Check Point Researchers have carried out a revealing investigation into North Korea’s home-grown anti-virus software, SiliVaccine. One of several interesting factors is that a key component of SiliVaccine’s code is a 10-year-old copy of one of Trend Micro’s, a Japanese company, software components.

Background

The journey began with our research team receiving a very rare sample of North Korea’s SiliVaccine anti-virus software from Martyn Williams, a freelance journalist with a focus on North Korean technology.

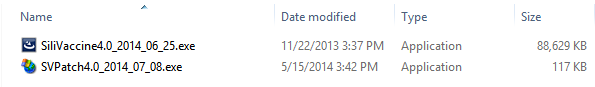

On July 8th 2014 Mr. Williams had himself received the software as a link in a suspicious email sent by someone going by the name of ‘Kang Yong Hak’, who’s mailbox has since been rendered unreachable. Upon taking a closer look, our team was able to uncover several interesting elements.

The strange email sent by ‘Kang Yong Hak’, supposedly a Japanese engineer, contained a link to a Dropbox-hosted zip file that held a copy of the SiliVaccine software, a Korean language readme file instructing how to use the software and a suspicious looking file posing as a patch for SiliVaccine.

Trend Micro’s AV Scan Engine

After detailed forensic analysis of SiliVaccine’s engine files, our team discovered exact matches of SiliVaccine and large chunks of anti-virus engine code belonging to Trend Micro, a completely separate Japan-based provider of cyber security solutions. Furthermore, this exact match coding had been well hidden by SiliVaccine’s authors. With Trend Micro being a Japanese company, and Japan and North Korea enjoying no official diplomatic or political relationship, this is a surprising discovery.

Of course, the purpose of an anti-virus is to block all known malware signatures. However, a deeper investigation into SiliVaccine found that it was designed to overlook one particular signature, which ordinarily it would be expected to block, and which is blocked by the Trend Micro detection engine. While it is unclear what this signature actually is, what is clear is that the North Korean regime does not want to alert its users to it.

Bundled Malware

Also found to be included in the SiliVaccine software that Marytn received was the JAKU malware. This was not necessarily part of the anti-virus but could be targeted towards journalists like Mr. Williams.

Also found to be included in the SiliVaccine software that Marytn received was the JAKU malware. This was not necessarily part of the anti-virus but could be targeted towards journalists like Mr. Williams.

In brief, JAKU is a highly resilient botnet forming malware that has infected around 19,000 victims, primarily by malicious BitTorrent file shares. It has however been seen to target and track more specific individual victims in both South Korea and Japan, including members of International Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), engineering companies, academics, scientists and government employees.

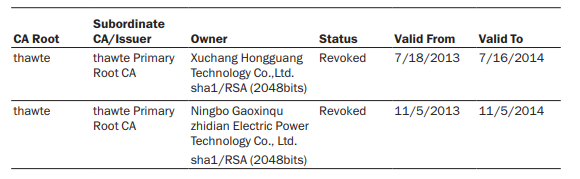

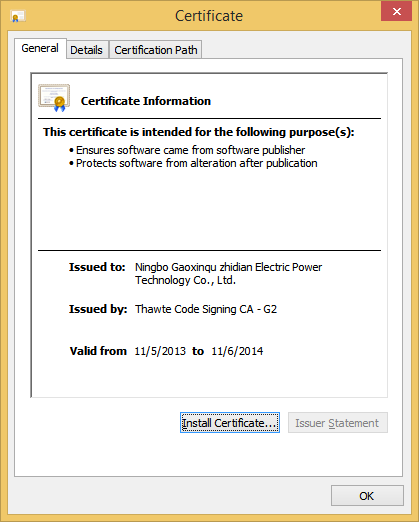

Our investigation found though that the JAKU file was signed with a certificate issued to a certain ‘Ningbo Gaoxinqu zhidian Electric Power Technology Co., Ltd’, the same company that was used to sign files by another well-known APT group, ‘Dark Hotel’. Both JAKU and Dark Hotel are thought to be attributed to North Korean threat actors.

The Japanese Connection

As well as the initial email containing the copy of North Korea’s anti-virus coming from a claimed Japanese sender, there were other connections with Japan found by our researchers.

During our investigation, we discovered the names of the companies that are thought to have authored SiliVaccine, two of which are PGI (Pyonyang Gwangmyong Information Technology) and STS Tech-Service.

Underlying these Japanese connections, however, is the non-relationship between Japan and North Korea, who are enemies with no official diplomatic relations.

STS Tech-Service seems to be a North Korean establishment, it has previously worked with other companies, including those by the names of ‘Silver Star’ and ‘Magnolia’, both of which are based in Japan.

Conclusion

This revealing exploration into SiliVaccine may well raise suspicions of authenticity and motives of the IT security products and operations of this Hermit Kingdom.

While attribution is always a difficult task in cyber security, there are many questions raised by our findings. What is clear, however, are the shady practices and questionable goals of SiliVaccine’s creators and backers.

Below are the full technical details of the investigation.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Contents:

Architecture and Overview

File Scanning Engine

Trend Micro’s Response

Pattern Files

Detection Naming Renaming Scheme

Malware Whitelisting

Kernel Drivers

Authorship Background

The Mysterious Patch File

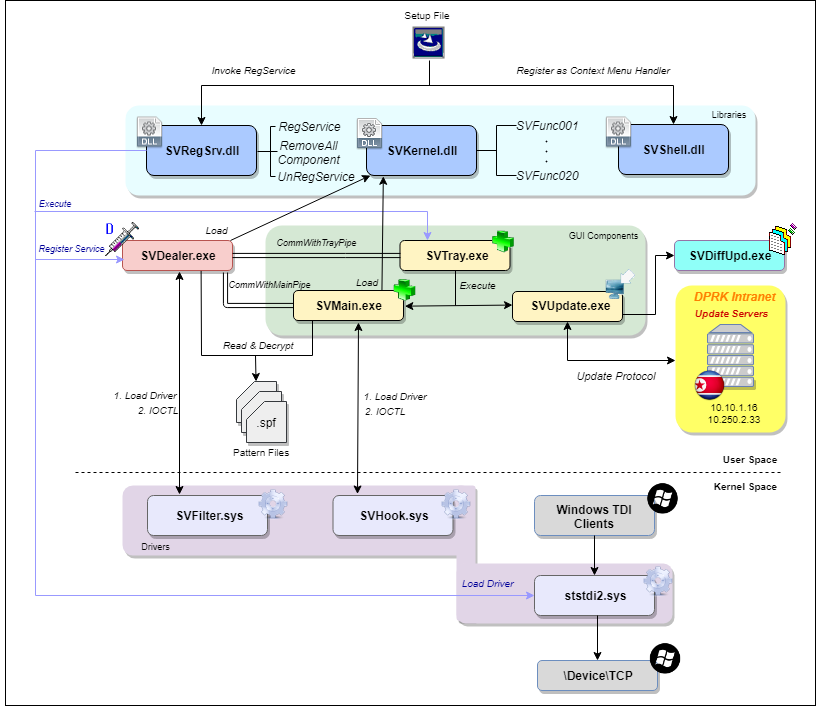

SiliVaccine has the structure of a rather classical Anti-Virus. It consists of both user and kernel mode components, all working together for the purpose of scanning files or memory against a given repository of static malware signatures (known as the pattern file). Generally, scans can be done on demand or in real time, each constituting a separate component to handle the scanning action accordingly. Either way, all are carried out by a single logic implemented in the core of the product, known as the engine.

The figure below gives a general overview of the various software elements that comprise SiliVaccine and their interactions, followed by an outline of each of the components and its purpose:

Figure 1: SiliVaccine’s architecture.

Libraries

- SVKernel.dll – the file scanning engine, the most substantial and important component of the AV. It has the core functionalities of detecting a file type, parsing it and going over its sections to locate any malicious indicators. The latter come in the form of signatures, which are designated for the engine and describe various properties that identify malware families or samples. These are stored as a group of 34 files – ranging from SVPatt00.spf to SVPatt33.spf, and can be read and interpreted by the engine during run time. All of the functions given by the engine are exposed through 20 DLL exports (SVFunc001 – SVFunc020), which are in turn used by the executables that conduct the scanning tasks. A deeper inspection of both the pattern files and the engine itself appears in the upcoming sections.

- SVRegSrv.dll – part of the installation package, which is in charge of deploying or discarding some of the AV’s components. The DLL gives 3 exports (apart from DllMain), each one taking a different course of actions:

- RegService: invoked by SiliVaccine’s MSI installer and used to activate the main components of the software. This is done by executing exe, registering SVDealer.exe as a service and loading ststdi2.sys as a driver. Apart from this, it creates a directory for quarantined files and scan logs, as well as creates elementary registry values that serve all the other components of the AV (e.g. the installation path, found in the AppPath key under HKLM\SOFTWARE\STS Tech-Service\SVaccine).

- RemoveAllComponent: removes all previously installed components, i.e. executables, DLLs, quarantine directory, scan logs and registry keys.

- UnRegService: Finds all relevant active windows with the names ‘SiliVaccine 4.0’ , ‘SiliVaccine 4.0 Update’ and ‘SiliVaccine 4.0 Patch’ and closes them by posting a WM_CLOSE window message. Additionally, it looks for the tray application by its window class (‘SVTRAY’) and shuts it down, unloads the sys and SVFilter.sys drivers and deletes the SVDealer.exe service.

Interestingly, the last 2 functions are never called, since there is no uninstallation utility for the software present amongst the installed files.

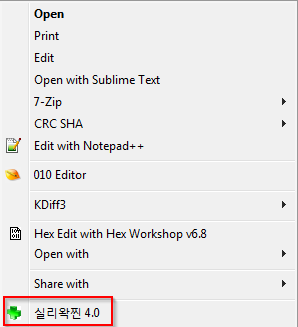

- SVShell.dll – a COM class serving as a shell extension, which is used to register a SiliVaccine context menu handler (as described in the figure below). This handler allows the scanning of particular files upon clicking the right mouse button; however no actual action takes place when doing so.

Figure 2: SiliVaccine’s context menu entry.

Service

- SVDealer.exe – user mode component registered as a service that is responsible for carrying out real-time scanning tasks. For this purpose, it loads a file system filter driver named SVFilter.sys, which intercepts various file system activities and signals the SVDealer component so as to trigger it to scan the files and report back with a verdict. The scanning itself is done by calling the corresponding export from SVKernel.dll (SVFunc018). A deeper explanation is given in the upcoming sections.

GUI Components

- SVTray.exe – the most essential GUI component appearing as a tray icon, which runs on the system constantly. The menu corresponding to the tray application (opened by right-clicking the icon) allows opening either the SVMain.exe or SVUpdate.exe components, or activating\disabling the real-time protection feature.

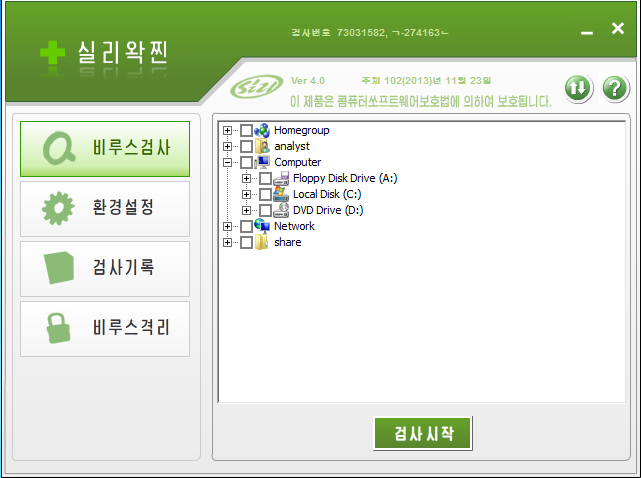

- SVMain.exe – the main window through which the user interacts with the software, which allows conducting manual scans on particular files\directories or changing various setting like file whitelisting, update scheduling etc. Also allows for the opening of the SVUpdate.exe utility.

Figures 3 & 4: SVMain GUI and SVTray menu.

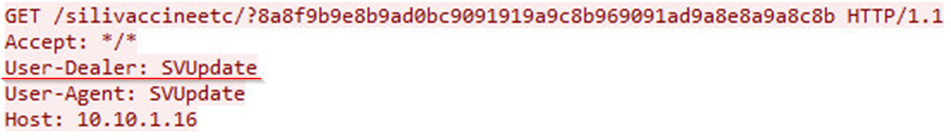

- SVUpdate.exe – an update utility which contacts intranet servers within the DPRK so as to poll for either new versions of the binary executables or pattern files.

The servers contacted can be hardcoded, in which case

they are 10.10.1.16 \10.250.2.33, or manually configured in the SVMain component. The communication protocol between the AV client and the update server is based on HTTP, with some peculiar additions such as the ‘User-Dealer’ field, which appears as an addition to the common ‘User Agent’ field:

Figure 5: Custom field appended to HTTP header during update request.

Each received update file is checked for integrity using a custom diffing tool called SVDiffUpd.exe.

Named Pipes

- CommWithMainPipe – used to pass the process ID of SVMain to SVDealer, which in turn passes it to the SVFilter driver via an IOCTL. The driver registers this number as a global variable (along with SVDealer’s PID). Upon access to any file on the system, the filter driver checks the PID of the associated process, and in case it’s that of an AV component (that is – either SVMain or SVDealer), the access is permitted.

- CommWithTrayPipe – used to notify the tray application of a newly attached removable media. For this, SVDealer generates a bitmask of currently available drives with the use of the GetLogicalDrives function, and monitors it for changes. Once a change is detected, SVDealer issues an IOCTL to attach the file system filter driver to new drive, sets a global event named RemovableMediaInsertEvent to be signaled and passes the drive index as a bitmask to SVTray via the named pipe. In turn, the tray application, which monitors for the pipe data indefinitely, sets a global event named MemoryScanEvent to be signaled, and issues the new drive index bitmask as window message to the ‘SVTRAY’ window.

Drivers

- SVFilter.sys – file system filter driver which communicates with the real-time protection service (SVDealer.exe). Some actions on the file system are intercepted so as to pass control to the aforementioned process for a prior scan. This will determine if the action should or should not take place, based on the scan verdict.

- SVHook.sys – a driver that interacts with SVMain upon a memory scan, in which case it provides various details related to the scanned process that are accessible solely through kernel mode.

- ststdi2.sys – a TDI driver which intercepts all TCP packets sent by system TDI clients. The driver logs all connections in a data structure and allows another entity to query it via IOCTLs.

It’s noteworthy that some of the components mentioned above (namely: SVKernel, SVDealer and all of the GUI components) are protected with Themida and Unopix, well-known and effective packers. While the usage of Themida is quite common in commercial software, in this case it’s somewhat puzzling; the reason for this being that it’s hard to break and provides very solid mitigations against reverse engineering. Considering the fact that SiliVaccine has no competitors in the North Korean market, it is not clear why this software has to be so protected. The following section may provide a possible explanation for using it.

One of the core elements of SiliVaccine is the scanning engine. This is in fact a DLL named SVKernel.dll which is responsible for carrying out a scan against a file or process memory so as to determine whether it’s malicious or not. In the former case it will also provide the detection name (i.e. the name of the signature triggered for that file), based on a repository of signatures referred to as the pattern file. This is probably the most important component of this software, and is being loaded by other utilities of the AV that invoke the scans themselves.

As mentioned in the previous section, the engine binary (as well as several others) comes packed with Themida 2.x and Unopix 0.94, both efficient software protectors that allow virtualizing parts of the code and providing various reverse engineering mitigations. This makes the resulting installed binaries fairly hard to analyze. Nonetheless, we were able to unpack the samples as almost no part of the code was virtualized and very few protection features were enabled in the first place.

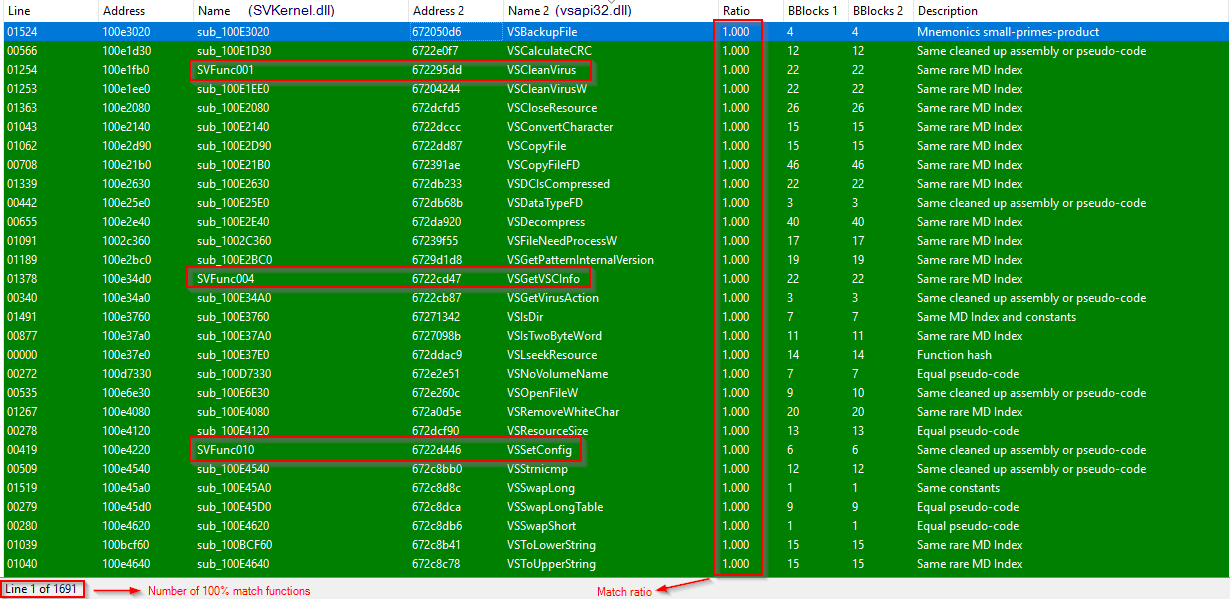

Looking at the unpacked binaries, we spotted strings that appeared in another file found on the internet named vsapi32.dll. As it turns out, this is a proprietary file scanning engine written by Trend Micro, a Japanese cyber security vendor manufacturing a range of AV solutions. Their engine serves the exact same purpose as the one found in SiliVaccine, and appeared highly similar to it.

In order to estimate the similarity between the two files we conducted binary diffing. Much to our surprise there is a great amount of code shared between them. In fact, as many as 1,691 functions had a 100% match based on very strong criteria (e.g. same function hashes, identical pseudo-code etc.). This finding is outlined in the following figure, which shows some of the results of the diffing process.

Figure 6: Results of a binary diff between SVKernel.dll and vsapi32.dll.

From the figure above it’s also evident that some of SVKernel’s export functions have an exact match to ones exported by vsapi32. As a matter of fact, at least 17 SVKernel exports are either precisely the same as ones in vsapi32, or are wrappers around such functions. The following is a table that shows the mapping we resolved between the two engines export functions, as well as few other ones that are written particularly for SiliVaccine:

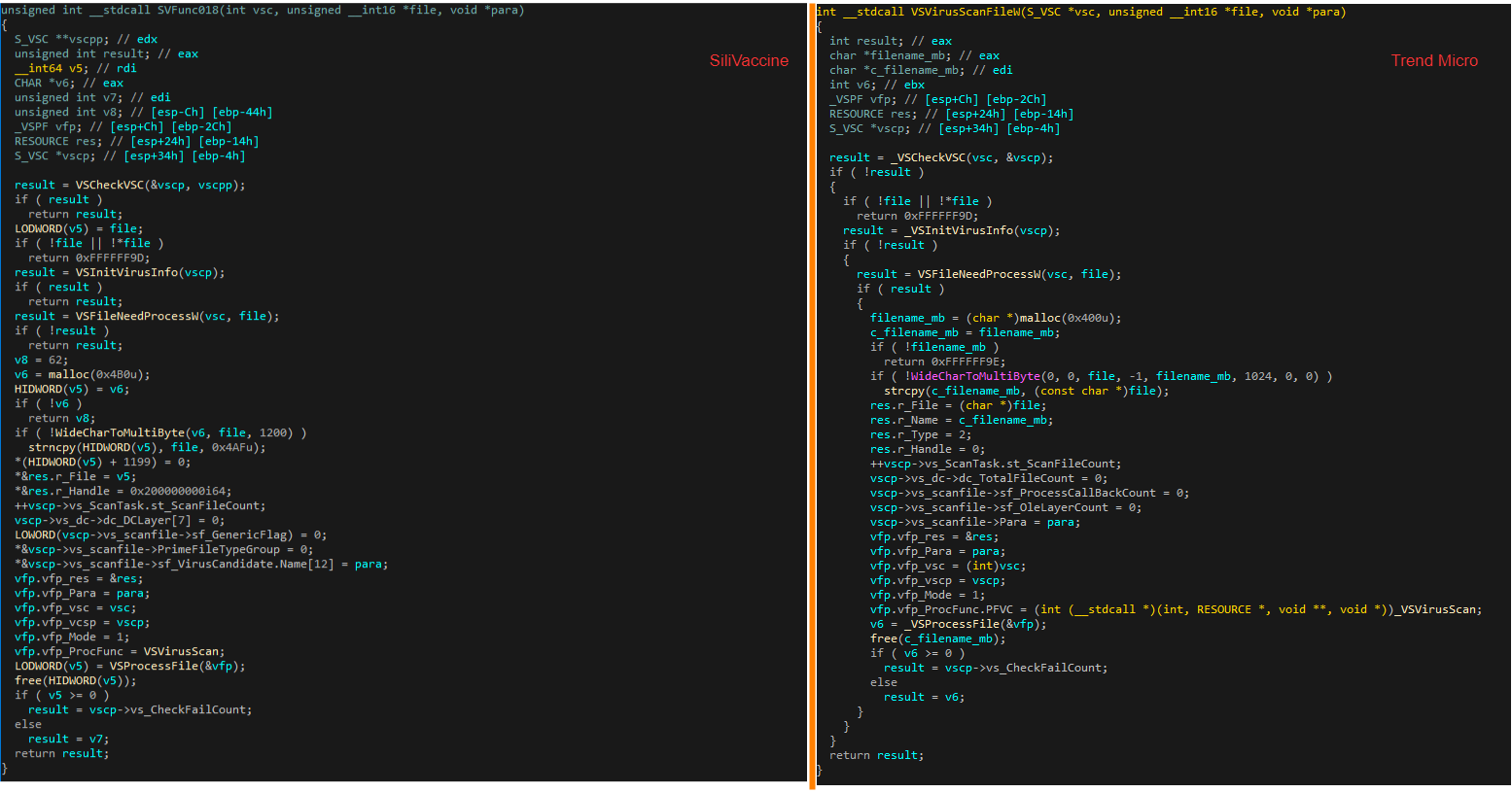

The following figures demonstrate the similarity of code in several key export functions. The first one corresponds to a function that sets all the parameters required for a scan task. Although the logic is practically the same in the two functions, there are some variations in the utilized internal data structures, which are evident through the allocation size for the corresponding structs. This may suggest that some adaptations were made to the structs so as to suite the SiliVaccine engine implementation.

Figure 7: Comparison between the virus scan function in SVKernel.dll and vsapi32.dll.

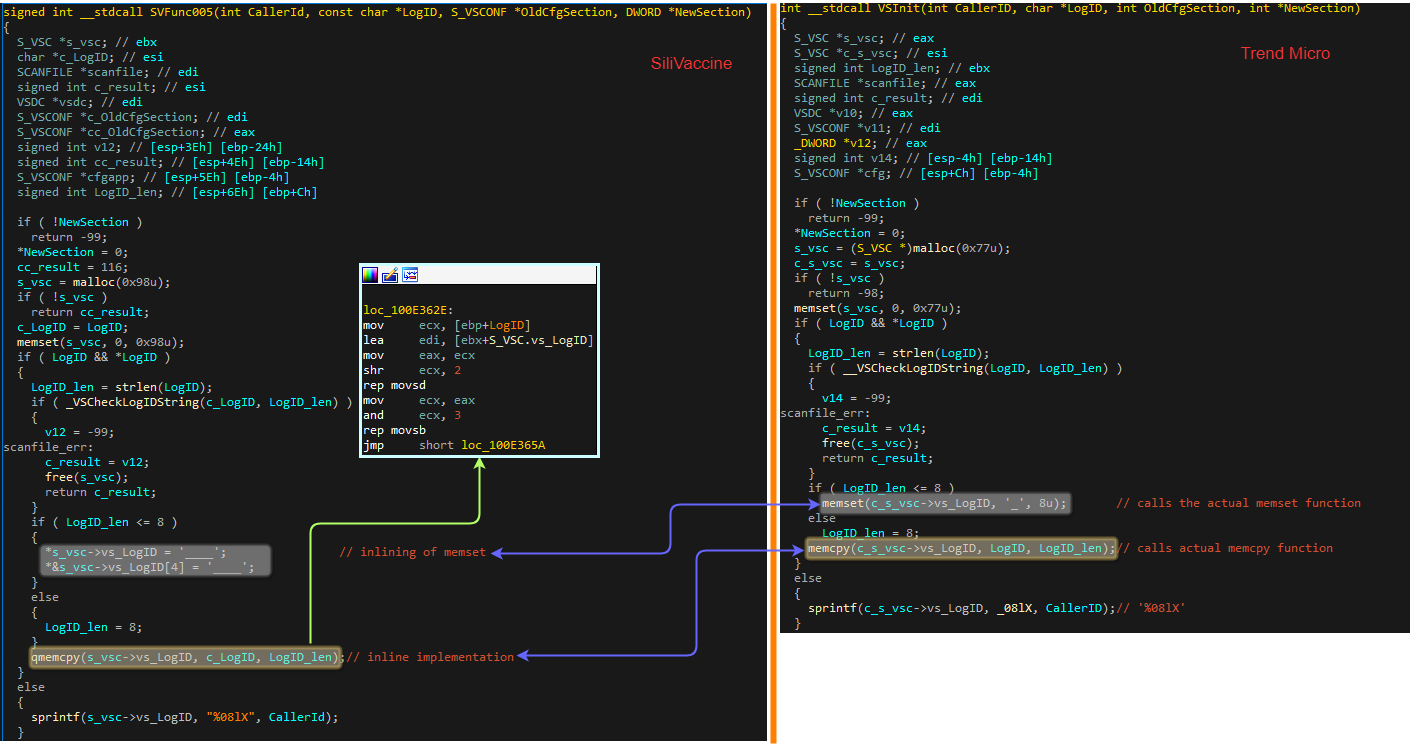

The next comparison is of a function that initializes fields in an internal configuration struct used throughout a scan. The particular field updated here is one corresponding to an ID given to the scan’s log file. An important difference can be witnessed between the functions – the SiliVaccine version uses inline versions of the memset and memcpy functions, while the Trend Micro engine actually calls the libc functions. This function inlining happens in a few similar places across the code, and suggests that possibly the Trend Micro source code was recompiled with an optimization that wasn’t used in the original engine.

Figure 8: Comparison between proprietary data structure

initialization functions in SVKernel.dll and vsapi32.dll.

Much similar to this, we can observe SVFunc004 which initializes an internal scan information structure. In this case, we witness function inlining once again – this time to the memcpy and strcpy functions. More importantly, if we look at the data put into the struct, we can see that one of the fields contains the actual version of the engine, which is hardcoded in the binary. Thus, we can infer that the Trend Micro engine leveraged by SiliVaccine’s authors is 8.910-1002. While information on this version is available online, it is pretty rare and harder to find than its successor (version 8.95) and predecessor (version 8.87). We can also tell that this engine version was released in August 2008, and was still deployed in the SiliVaccine version we were examining, which is known to be from 2013.

Figure 9: Comparison of scan info struct initialization functions in SVKernel.dll and vsapi32.dll.

Finally, if we look at scan cleanup function at SVFunc006, which removes various AV file & memory artifacts, we see a key difference between Trend Micro and SiliVaccine’s engines. If we look at the SVKernel version of the function, we can spot a call to a native function used to unload and cleanup a legacy SiliVaccine driver named SVIO.sys. This driver doesn’t exist in this version of the AV, and has nothing to do with vsapi32 nor Trend Micro.

Figure 10: Comparison of scan info struct initialization functions

in SVKernel.dll and vsapi32.dll.

At this point, it is pertinent to mention that we reached out to notify Trend Micro of their detection engine being used in SiliVaccine. They responded very promptly and were highly cooperative with our team. Their response was as follows:

“Trend Micro is aware of the research by Check Point on the ‘SiliVaccine’ North Korean anti-virus product, and Check Point has provided us with a copy of the software for verification. While we are unable to confirm the source or authenticity of that copy, it apparently incorporates a module based on a 10+ year-old version of the widely distributed Trend Micro scan engine used by a variety of our products. Trend Micro has never done business in or with North Korea. We are confident that any such usage of the module is entirely unlicensed and illegal, and we have seen no evidence that source code was involved. The scan engine version at issue is quite old and has been widely incorporated in commercial products from Trend Micro and third party security products through various OEM deals over the years, so the specific means by which it may have been obtained by the creators of SiliVaccine is unknown. Trend Micro takes a strong stance against software piracy, however legal recourse in this case would not be productive. We do not believe that the infringing use at issue poses any material risk to our customers.”

Trend Micro’s indication that a widely licensed library was misappropriated may be behind SiliVaccine’s use of a 10+ year-old version of their scan engine is backed up by an additional analysis our team made of an older version of SiliVaccine, too. This suggests that this is not a one-time occurrence.

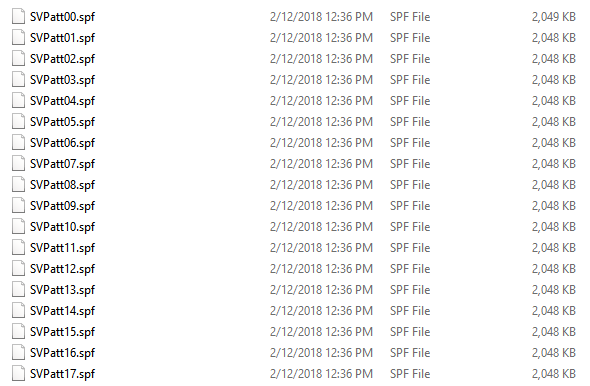

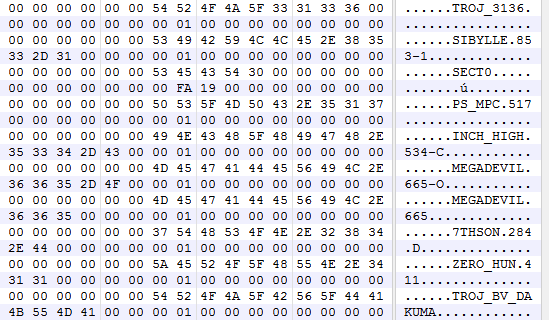

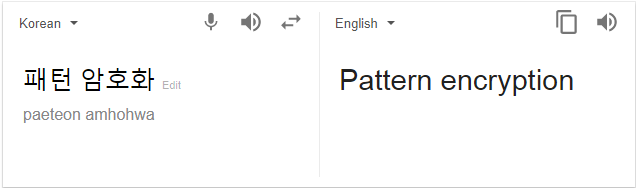

SiliVaccine’s malware signatures are stored in a series of files called Pattern files. A Deeper look into these files reveals they are in fact a Trend Micro’s pattern file (lpt$vpn file), encrypted and divided into 2MB chunks. This is hardly surprising due to fact that SiliVaccine uses Trend Micro’s scanning engine.

Figure 11: Listing of files that comprise the overall signature repository used by SiliVaccine, known as the pattern file.

The pattern files are encrypted with what seems like a custom encryption protocol that also utilizes a slightly modified SHA1 hashing algorithm. While understanding the encryption algorithm itself is quite a challenge, it’s also not really necessary, as the decrypted pattern file can simply be dumped from memory after the decryption:

Figure 12: Part of a memory dump containing the decrypted pattern file.

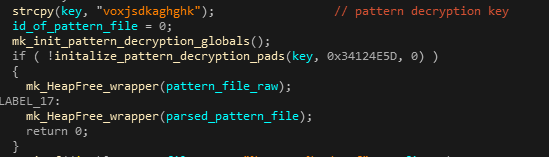

One entertaining fact regarding the decryption process is the decryption ‘key’.

The key seems to be a combination of random English letters. However, if typed on a Korean-English keyboard when the language is set to ‘Korean’, you would get the Korean phrase that translates literally to ‘Pattern encryption’.

The function SVFunc019 exported by SVKernel is responsible for reading, decrypting and parsing the pattern files. It does so by reading each file, decrypting it, and appending it to a global buffer where the complete decrypted buffer is stored:

Figure 13: Pattern file loading and decryption code.

SVMain and SVDealer call the proprietary SVFunc019 function in order to load and decrypt the pattern file, and from there they use Trend Micro’s code (SVFunc007 – VSReadPatternInFile) in order to parse and load the signatures themselves.

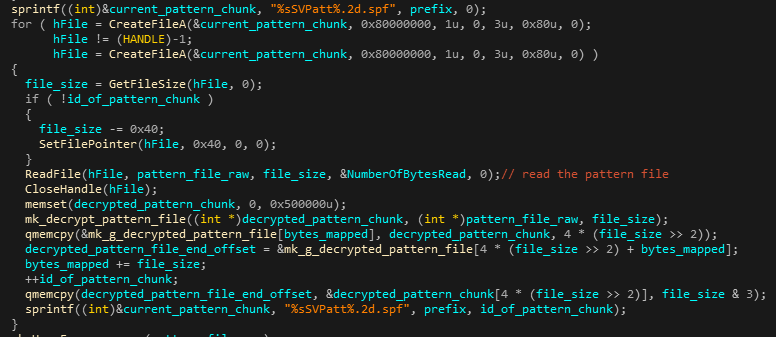

Detection Names Renaming Scheme

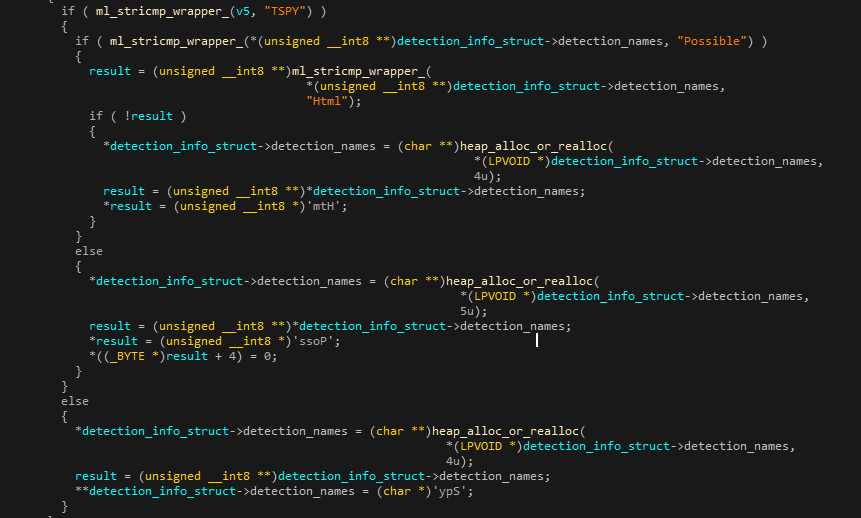

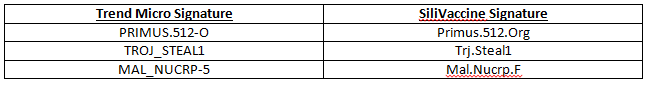

As previously described, SiliVaccine uses Trend-Micro’s pattern files, which contain Trend Micro’s signature names. However, these names are never revealed to the end user, as it performs internal renaming of detected malware names, essentially converting them from Trend Micro’s format into its own “proprietary” format. This functionality is handled by dedicated functions in the SVMain & SVDealer modules, set as a callback by calling the SVFunc016 (VSSetProcessFileCallBackFunc) export in SVKernel, and triggered right after each file scan. If the scan detected a malware, the matching detection name is taken as it appears in the pattern file and converted into a custom format as described below. Throughout the program only the modified name format is referenced, as described further in the whitelisting section.

The renaming method works as follows:

- The detection name from the pattern file (as reported by the SVKernel scan) is split into parts by searching for the following delimiters: “-“, “_”, “.”

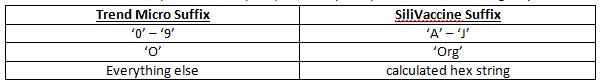

- The first part (the prefix), which usually specifies the malware type/category, is replaced according to the following table.

Other prefixes are used as-is. The prefix replacement is shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 14: Detection name prefix replacement code.

3. If there are more than 2 parts, the last part (the suffix), is replaced in the following way:

4. If there are more than 3 parts, the part before the suffix is replaced with a calculated hex string.

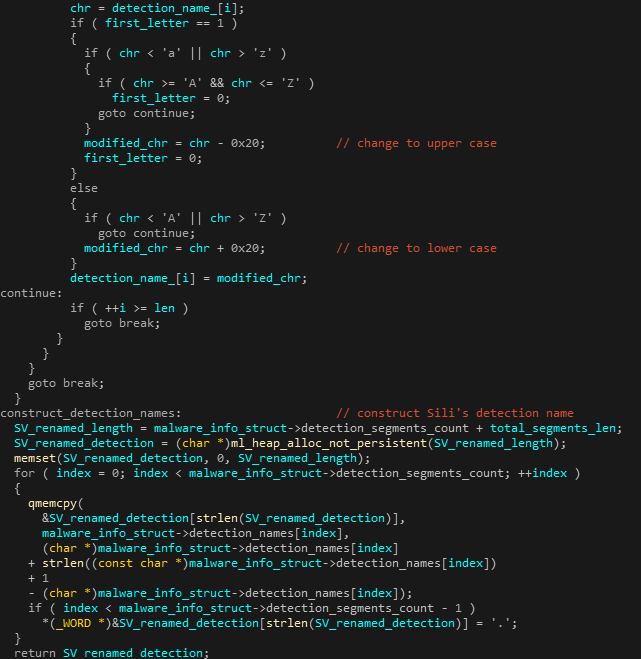

5. For each part, the first letter is converted to uppercase and everything else to lowercase.

6. A new name is constructed by joining all the parts with a dot (.) separator:

Figure 15: Constructing the final renamed detection name.

Here are a few examples of Trend Micro names and their matching SiliVaccine names.

During our research we discovered that the authors of SiliVaccine have chosen to white-list a single very specific malware signature, and effectively ignore any detection of files matching that specific signature. The white-listed signature is Trend Micro’s ‘MAL_NUCRP-5’, described by Trend Micro as:

“…the Trend Micro detection for suspicious files that manifest behavior and characteristics similar to known NUWAR, TIBS, and ZHELAT variants.”

This signature doesn’t seem to be related to any one specific malware, but rather seems to detect specific packing related characteristics common in some malware. The ‘MAL’ prefix used in this signature indicates this is a generic signature, described by Trend Micro as a ‘Second Level Generic Detection Name’, essentially a heuristic signature created by observing a common pattern in existing malware. Unsurprisingly, Looking at a group of around 20 different files detected as MAL_NUCRP-5 reveals vastly different and un-related malware samples, ranging from fake AV installers to a dropper component seemingly related to a Chinese APT attack.

The white-listing functionality is hard-coded in the binary components of the program itself and is handled by implicit comparisons in the code that were added solely for that purpose. This effectively equals to removing the signature completely, which would have made more sense. However, the signature itself is still present in the pattern files that came with SiliVaccine. This indicates that the authors either have no direct way of modifying Trend Micro’s pattern files, or no interest of doing so every time they update them.

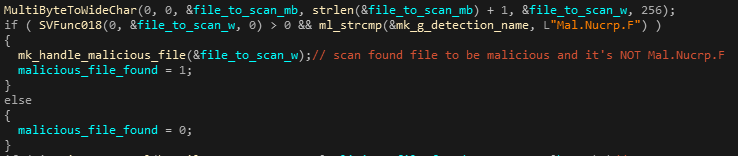

Getting into the details, the white-listing is implemented by SiliVaccine’s two major components; SVMain & SVDealer – namely, the components that invoke file scans using SVKernel. In multiple places throughout the code, immediately after the export function SVFunc018 (VSVirusScanFileW) is called, the global string that stores the last scan’s detection name is compared to ‘Mal.Nucrp.F’. That string is actually Trend Micro’s detection name ‘MAL_NUCRP-5’ after SiliVaccine’s renaming. In case the detection name does equal ‘Mal.Nucrp.F’, the code branches out to continue as if the scan didn’t find anything (ignoring the detection completely).

Figures 16 & 17: White-listing the Mal.Nucrp.F detection, following a file scan.

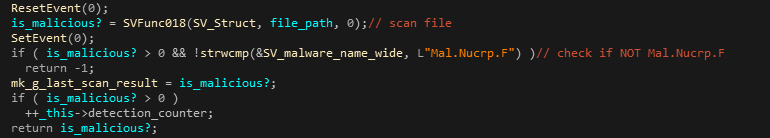

Another instance of this type of comparison can be found in the SVMain module, specifically in the renaming callback function that that was previously described. However, it’s amusing to note that the authors seem to have made a typo this time and wrote ‘Mal.Nurcrp.F’ (with an extra ‘r’ in the middle) by mistake.

Figure 18: Typo in the white-listing comparison to Mal.Nucrp.F detection.

This does not affect the white-listing functionality however, since an extra implicit comparison is made after each scan instance anyway.

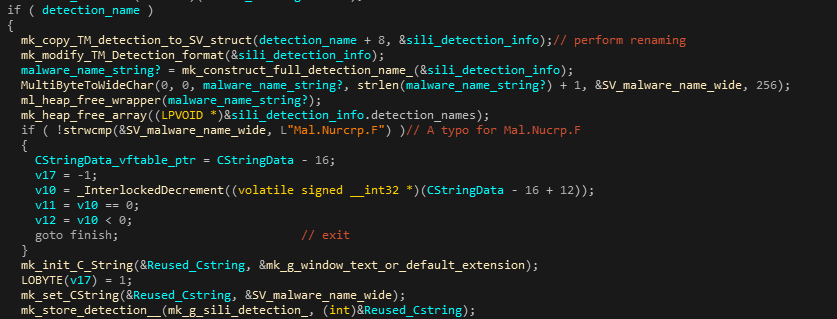

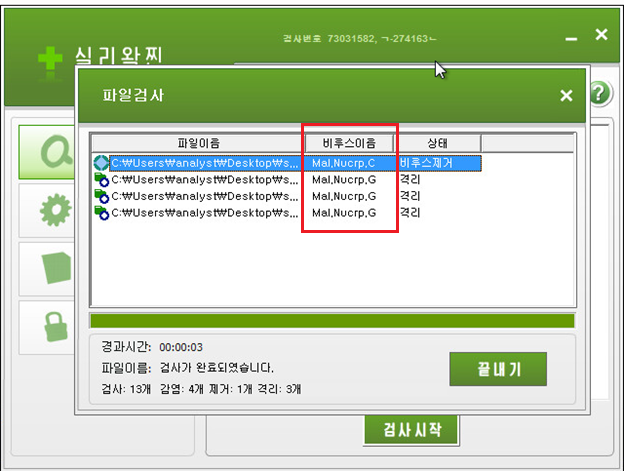

It’s interesting to note that all the other similarly named signatures (MAL_NUCRP-*) are not whitelisted. A scan of a group of files detected by Trend Micro as ‘MAL_NUCRP-2’ (1 unique file), ‘MAL_NUCRP-5’ (8 unique files) and ‘MAL_NUCRP-6’ (3 unique files) is shown below:

Figure 19: No detection MAL_NUCRP-5, as opposed to MAL_NUCRP-2 and MAL_NUCRP-6.

Note how files that should have been detected as ‘Mal.Nucrp.F’ are all notably missing, while the other files (Mal.Nucrp.C & Mal.Nucrp.G) are all correctly detected.

SiliVaccine uses 3 driver components:

- SVHook.sys – Kernel-mode process information collection module.

- SVFilter.sys – File system filter driver used for real-time and AV files protection.

- ststdi2.sys – Network Transport Driver Interface (TDI) Driver.

Protection Mechanisms

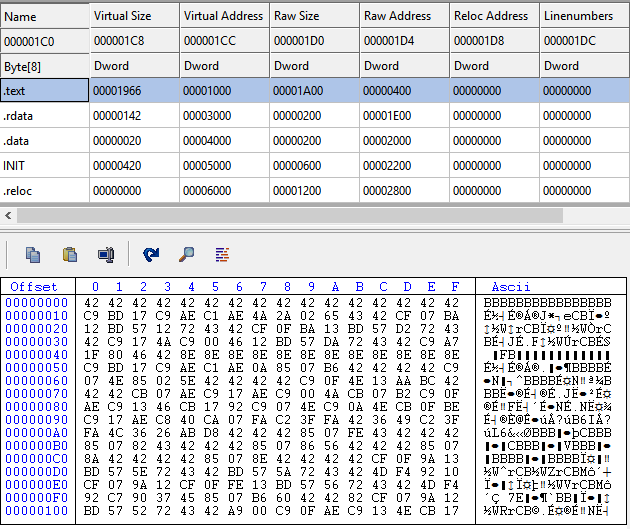

Both SVHook and SVFilter drivers are ‘packed’ with a strange packer detected as ‘BobCrypt2 protector’ by Detect-It-Easy. This is an obscure detection which seems like a false positive, as the packer employed here would hardly qualify as a protector. Instead, the packing used is a simple XOR of the .text section, with the byte 0x42, something that easy to spot when looking at it:

Figure 20: .text section encrypted using a simple XOR with 0x42.

The EntryPoint of the binary is in the “.reloc” section, which contains the packer’s code.

SVFilter

The SVFilter.sys component is a file system filter driver utilized by SiliVaccine for 2 main purposes:

- Real-time protection functionality – together with SVDealer, the user-mode component.

- Protecting SiliVaccine’s binary components from deletion and modification.

Real Time Protection

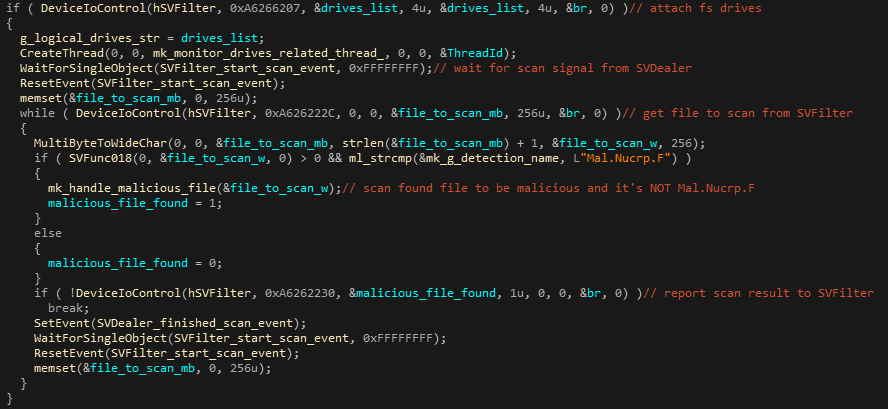

The Real-time protection functionality is implemented by SVDealer, which uses the SVFilter driver to hook file system activity and scan files that are being accessed in real-time. SVFilter is loaded by SVDealer which communicates and controls it with it via IOCTLs. SVDealer instructs the driver to attach itself to all existing file system driver stacks, and then waits for a scan signal from the driver. Once the signal arrives, it reads the file path that needs to be scanned via a separate IOCTL, scans it, and reports back to SVFilter whether the file was found to be malicious (and not white-listed). The following screenshot shows this functionality from SVDealer’s side:

Figure 21: Conducting a scan by SVDealer, following a signal from SVFilter (real-time protection from SVDealer’s side)

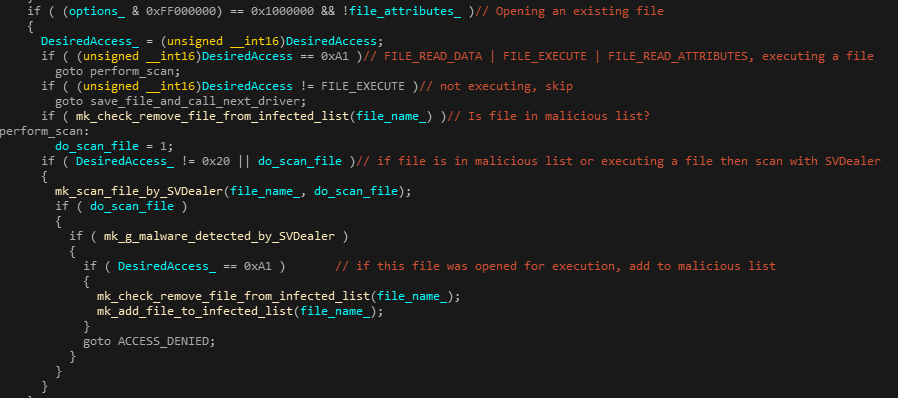

The matching functionality on SVFilter’s side is buried deep inside a long and confusing function. After analyzing that function, it becomes evident that it is rather needlessly long and complex, and underneath it all, it simply performs the functionalities described above in a disorganized and confusing way. After multiple overlapping and weirdly specific checks, the function finally arrives to the real-time scanning functionality. The real-time file scan is only invoked upon execution of files. The code checks if the file is opened for execution, and if so stores the file path and signals SVDealer that a file needs to be scanned. Afterwards it checks the result reported by SVDealer. If the file is reported malicious, its name is stored in a list (whose purpose is not completely clear as it’s not used in any sensible way), and access to file is blocked. The following snippet of code shows this functionality:

Figure 22: Signaling SVDealer regarding file execution, and handling retrieved scan results (real-time protection from SVFilter’s side).

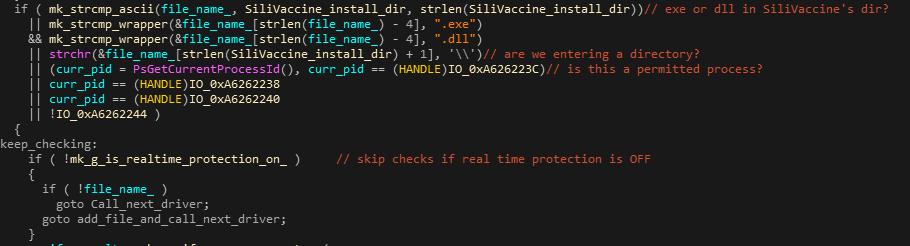

Protection of Internal Components

The same filter function in SVFilter also protects SiliVaccine’s binary files on disk by blocking any write access to them. The following screenshot displays the code segment that performs the relevant checks:

Figure 23: Protecting SiliVaccine files on disk by SVFilter from any write access.

SVHook

The SVHook driver is an odd and somewhat confusing component. The name implies it’s used for kernel-mode hooking, but it doesn’t contain any such functionality. Instead it is loaded and utilized by SVMain in order to query windows object metadata from the kernel when SiliVaccine performs a memory scan of the system. It essentially serves as a kernel mode agent to query information accessible only from the kernel.

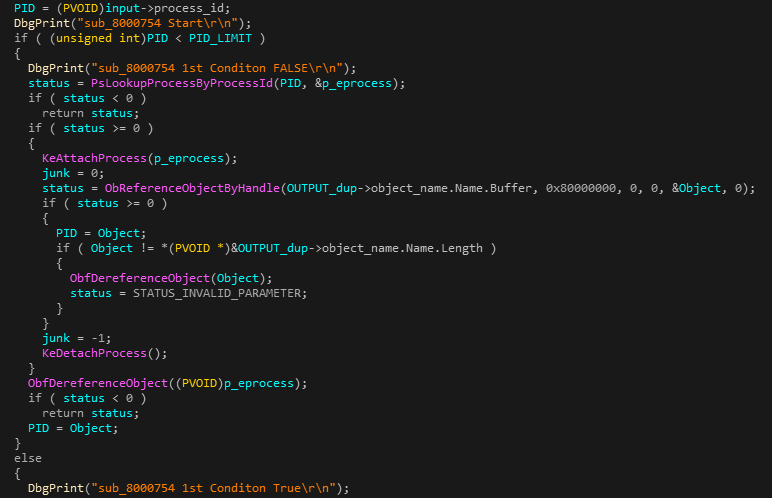

The most interesting thing about this component is the debugging strings left in the code by the authors. One the functions in SVHook contains multiple DbgPrint calls, describing the state of the function, while referencing to the function itself as ‘sub_800754’:

Figure 24: Peculiar debug strings appear in SVHook’s binary.

This is most probably an auto-generated name by the IDA reverse-engineering tool, indicating this function may have been copied from another driver the authors have reverse-engineered. The function itself seems to receive a handle from user-mode and returns the matching object name.

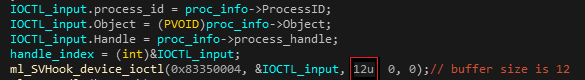

It’s also interesting to note that the driver supports 13 IOCTL commands, while only 3 are ever called by the user-mode components (SVMain). Additionally, the driver seems to contain several bugs and mistakes that indicate this component was slapped together quickly and without fully understanding the purpose. For example, one of the used IOCTLs will always fail since the authors seem to have made a mistake in their condition statement: The input buffer size sent in the IOCTL by SVMain is 12 bytes (as it should probably be):

However, the authors seem to have mixed up the condition when verifying the size of the input in SVHook, and they return the status code STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER when that’s the case:

Figures 25 & 26: Programming mistake in buffer length check,

when handling the 0x83350004 IOCTL by SVHook.

STSTDI

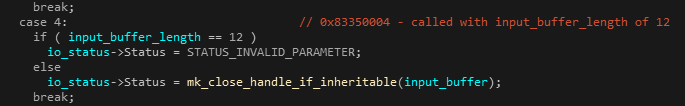

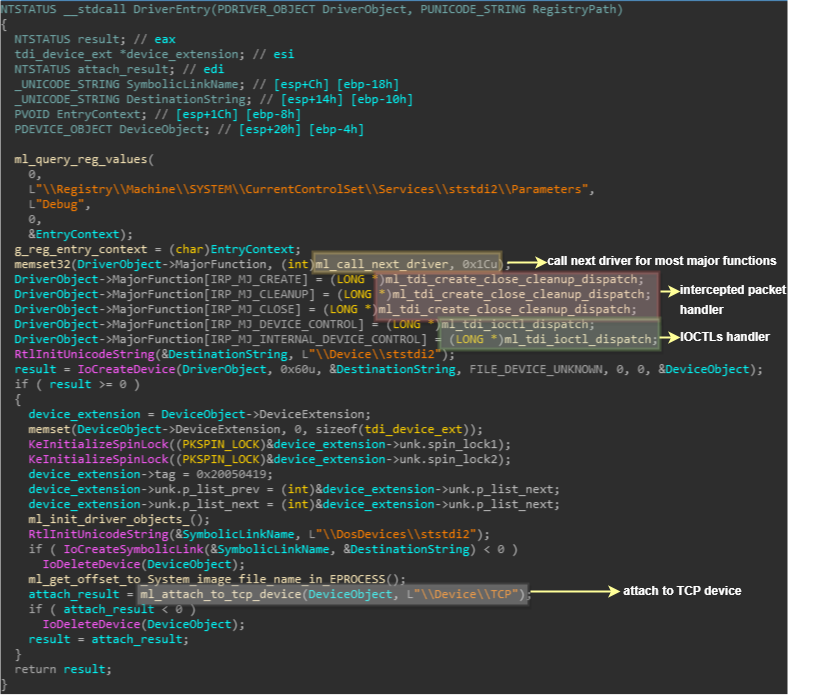

The final driver that can be found amongst SiliVaccine’s components is ststdi2.sys. This is a TDI (Transport Driver Interface) filter driver, which is used to intercept TCP connections and log them in an internal data structure. The way this is done is by having the device corresponding to this driver attach on top of the system’s TCP device, thus intercepting IRPs from higher level kernel TCP clients (for instance HTTP.sys, which uses the TDI API to communicate with TDI transport drivers).

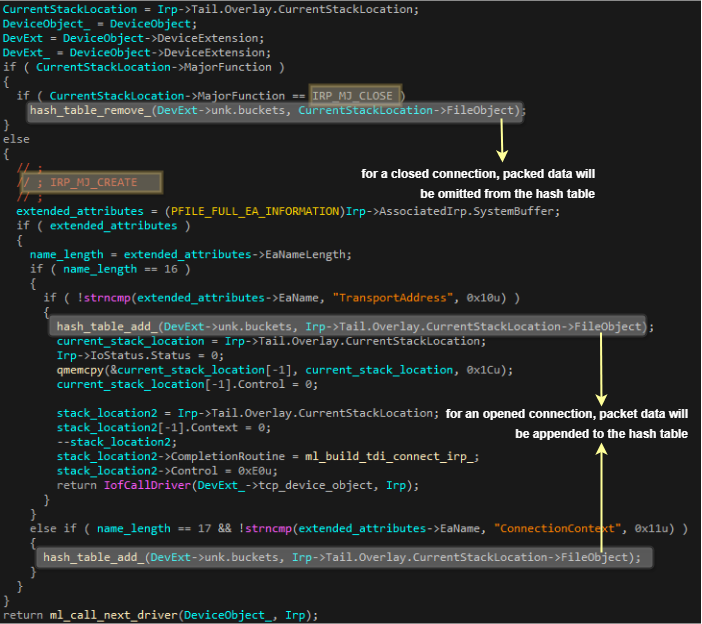

If we observe the DriverEntry, we can see 3 dispatch functions. The first is a default function that just passes the IRP onwards to the TCP driver, making the TDI driver “transparent” for most cases. The second is the dispatch function that handles IRP_MJ_CREATE, IRP_MJ_CLEANUP and IRP_MJ_CLOSE,

which will intercept any events of connection creation or termination. Finally, for IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL or IRP_MJ_INTERNAL_DEVICE_CONTROL the driver will deal with any particular passed IOCTLs.

Figure 27: STSTDI’s DriverEntry function,

showing the main dispatch routines and attachment to the TCP device.

The dispatch function that handles connections attempts to log them in a hash table, such that it will contain all the active connections at every point in time. In the figure below it can be seen that in the case of IRP_MJ_CREATE, i.e. connection creation, a system buffer associated to the IRP will be inspected and will determine if the connection address or context get appended to the hash table. In the same manner, upon interception of IRP_MJ_CLOSE (connection termination), the corresponding connection data will be located in the hash table and removed.

Figure 28: Handling of intercepted packets by STSTDI.

To use this logged data, the driver contains a handler for a set of IOCTLs, which allow an external entity (another driver or a user space component) to query and modify the underlying hash table. Strangely enough, there is no other component in the AV that actually issues these IOCTLs, making this driver seem redundant. It could be so that this is a legacy component, i.e. one that was previously incorporated but remained in the software even though it wasn’t used.

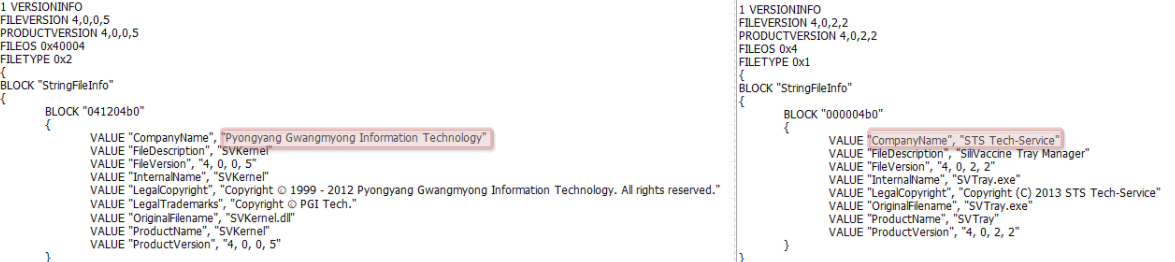

So far, we have seen the technical implementation specifics of various SiliVaccine components. There are however some intriguing details that can be found by looking at file meta-data. Namely, if we observe the version info resident within the resource section of the AV’s PE components (which is only accessible in the unpacked versions of the files), we can spot two company names – PGI (or Pyonyang Gwangmyong Information Technology) and STS Tech-Service.

Figure 29: Company names hiding in the version info of SiliVaccine’s binaries.

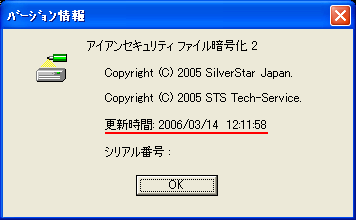

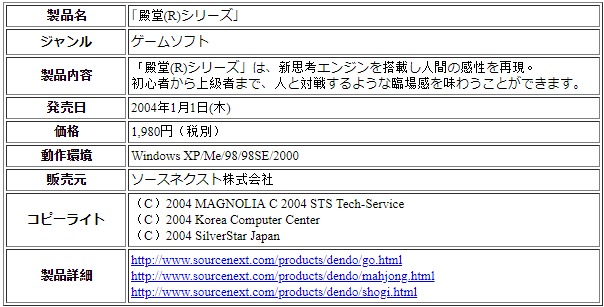

While we can guess from the name Gwangmyong, which is most likely a misspelling of Kwangmyong (DPRK’s national intranet) that PGI is likely a North Korean establishment, STS Tech-Service remains somewhat of a mystery. This supposed company has no internet website or clear record of activity on the internet, leaving some question marks regarding its origins and line of business.

Nonetheless, some clues are publically available in the web, but rather than giving clear answers to the aforementioned questions, they leave room for more pondering. One example for this is the fact that STS Tech-Service is listed as a co-author of multiple Japanese applications, written alongside two companies – Silver Star Japan and Magnolia. Programs like Mahjong (popular Asian tile-based game) or Iron Security (file encryption utility), seem like legitimate apps developed by these companies for the Japanese market. Does this mean that STS Tech-Service is in fact based in Japan?

Figure 30: Examples of applications developed by STS Tech-Service

in collaboration with Japanese companies.

A more in-depth inquiry of this company gives evidence that it’s not actually the case. Looking at an invitation brochure to an event titled “Pyongyang International Technology and Infrastructure Exhibition” that took place in North Korea back in 2006 we can see STS Tech-Service listed as one of the participating companies. The event’s original purpose was to encourage cooperation between DPRK based businesses with other worldwide foreign companies. While a lot of the companies that can be seen in this brochure are based in various parts of the world, STS Tech-Service seems to be actually situated in the DPRK, according to information from the exhibition organizers.

Figure 31: Invitation to ITIE, an exhibition that took place in Pyonyang in 2006. STS Tech-Service was one of the participating companies.

As previously mentioned, the copy of the installation file of SiliVaccine was sent to us by Martyn Williams, a freelance journalist, which in turn received it from a mailbox of a mysterious sender from a Japanese origin.

The Installer file is named ‘SiliVaccine4.0_2014_07_08.exe’, implying it is SiliVaccine version 4.0 dated 08.07.2014. Examining the file reveals it is actually a WinRAR SFX archive, containing an older dated installer and a supposed ‘patch’ file.

Figure 32: The contents the received installer file.

Upon execution of the SFX archive, both of the files inside are executed in turn, automatically. The older dated installer file inside is indeed the legitimate installer of SiliVaccine. A closer look at the supposed patch file however, reveals it to be a cleverly disguised JAKU malware instead, specifically a Stage 1 dropper.

It is interesting to note that the file is signed by a certificate that is extremely similar to one of the certificates reportedly used in the DarkHotel APT campaign. This makes sense – the JAKU campaign report states there are “clear connections” between JAKU and DarkHotel, implying the actor behind may be the same, while the DarkHotel Report by Kaspersky suggests that the actor behind the attacks has performed certificate theft. It’s interesting to note that both of these campaigns contain possible links to North Korea.

Figure 33: The certificate used to sign the JAKU sample.

Figure 34: Stolen certificates used in the DarkHotel campaign,

taken from Kaspersky’s DarkHotel report.