Introduction

As reported by Check Point at the end of H1 2022, 1 out of 40 organizations worldwide were impacted by ransomware attacks, which constitutes a worrying 59% increase over the past year. The ransomware business continues to grow in gargantuan proportions due to the lucrative payments demanded – and often received – by cybercrime gangs. With the addition of double extortion, ransomware attacks became even more appealing: even if the victim refuses to pay, the stolen private data may be sold in a Darknet forum for a considerable sum.

Gone are the days when cybercrime attacks were carried out by lone enthusiasts, occasionally aided by some friends and like-minded persons. As uncovered in a recent Conti leak, the backend of a modern high-profile cybercrime operation is reminiscent of the structure of giant IT companies whose employees may be located all over the world, with dedicated roles and responsibilities. Judging by the attention to detail we observed in a recent Black Basta incident spotted by the Check Point Incident Response Team, the operators behind this ransomware also have an impressive organizational structure.

*Since May 2022, there were more than 89 cases of high-profile organizations who were extorted by the Black Basta gang. Data shows the group’s clear geo-specific focus on the US and Germany; 49% of the victims listed on the shame site are US accounts. The ransom demand in some cases exceeded 1 million USD.

| Country | Number of victims | Percentage of victims |

| United States | 44 | 38% |

| Germany | 16 | 14% |

| United Kingdom | 4 | 3.5% |

| Austria | 3 | 2.6% |

| Canada | 3 | 2.6% |

| Switzerland | 3 | 2.6% |

| Denmark | 2 | 1.74% |

| France | 2 | 1.74% |

| India | 2 | 1.74% |

| Italy | 2 | 1.74% |

| Other | 6 | 5.22% |

| Total: | 87 | 100% |

Figure 1 – *Top 10 victims’ countries according to leak sites.

In the article below, we describe the inner workings of a Black Basta campaign and pay special attention to the delivery stage where the main preparations for a smooth ransomware execution are made. We explain all the numerous evasions and anti-analysis techniques that prevent emulators and sandboxes from detecting and analyzing the threat in an automated mode. We provide links to our Anti-Debug and Evasions encyclopedias in each corresponding entry: these sites are the ultimate sources of numerous techniques grouped by categories, with code examples and possible counter-measures to take. Last, but not least, we present an overview of how Black Basta encrypts files in the system and how it is capable of lateral movement.

Technical details

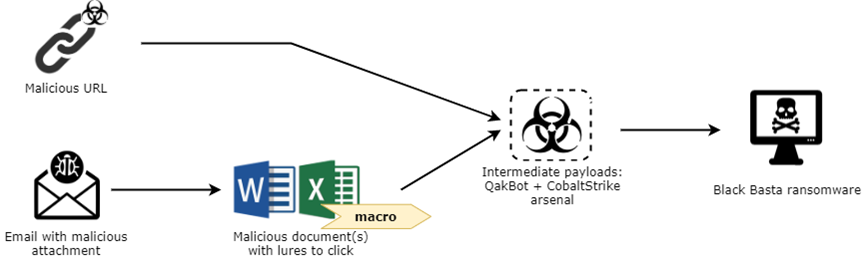

Before the actual ransomware execution can start, the ransomware must be delivered to the victim’s machine. With the creativity and developed social skills of cybercrime syndicate members, there are different ways for the dropper to deliver its payload to the selected victim’s machine. There can also be a chain execution of dropper modules (we observed the combination of QakBot and Cobalt Strike payloads) which finally leads to the ransomware execution.

Figure 2 – Possible ways Black Basta delivers ransomware to the victim’s machine.

We observed that droppers can be much more sophisticated than just a technically simpler ransomware payload. We describe the final delivery stage of the Black Basta ransomware below.

Delivery stage

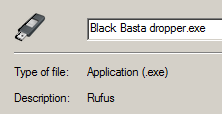

The Black Basta dropper mimics the application for creating USB bootable drives hosted on this site:

Figure 3 – Icon and description of the Black Basta dropper.

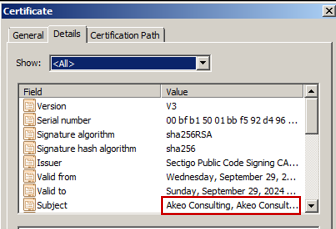

The application is digitally signed with the same certificate (issued by “Akeo Consulting”) used for legitimate executables from the Rufus website:

Figure 4 – Digital signature of the Black Basta dropper and the certificate issuer.

For more information on how to create a malicious application with a verified digital signature, see the dedicated article by the Check Point Research Team.

Evasion and anti-analysis techniques

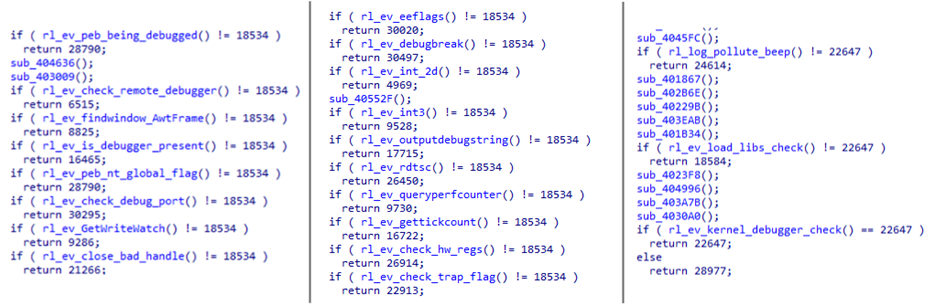

There are quite a few anti-debug tricks implemented in the Black Basta dropper, listed below grouped by categories. Click the links for more information.

Figure 5 – Anti-debug and evasion techniques in the Black Basta dropper.

If any of these techniques is successful in detecting a debugger and/or an emulation environment, the dropper stops its execution and quits without launching Black Basta.

System flags

This group of anti-debug techniques relies on in-process structures to check the status: whether it is being debugged.

- PEB: is debugger present

- PEB: being debugged

- PEB: NtGlobalFlag

- CheckRemoteDebugger

- Check kernel debugger

CPU registers

The techniques grouped below use CPU registers to check if the process is being debugged.

- Set trap flag

- Check trap flag, same as above. Flag is not set, just checked

- Check HW breakpoints (method 1 in the link)

CPU instructions

These techniques use CPU instructions via direct calls or wrappers to check if the process is being debugged.

Timing checks:

These techniques perform timing checks to see the differences between the debugged process and the one that is run without a debugger.

Library checks:

This technique relies on the assumption that there are some common system libraries in the usual system that can be loaded without issues, and that there are also some uncommon ones that should not really be present in a typical system. However, in a sandbox environment, when trying to load an uncommon library, the pre-defined code may be returned instead of what is returned in a non-emulated machine in these cases. The difference in returned code can be all it takes to detect the sandbox.

Libraries that must be loaded:

- kernel32.dll

- networkexplorer.dll

- NlsData0000.dll

Libraries that must not be loaded:

- NetProjW.dll

- Ghofr.dll

- fg122.dll

Windows API checks

The following group of techniques uses Windows API functions to detect if the process is being debugged.

- VirtualAlloc in conjunction with GetWriteWatch

- CloseHandle with bad descriptor

- OutputDebugString to check last system error

Log pollution:

This technique is not really an anti-debugger but makes the log analysis harder. The main point is to make a random number of calls to the kernel32.beep function. You can see more in this sandbox analysis.

Failing checks due to coding error

These checks are supposed to use specifics of either the emulation environment or a debugged process but fail to work properly due to errors in the coding.

- FindWindow (class name: ▬unAwtFrame) – The first symbol in the name is wrong; it should be SunAwtFrame

- NtQueryInformationProcess, check DebugPort – Doesn’t work because of a wrong dll name

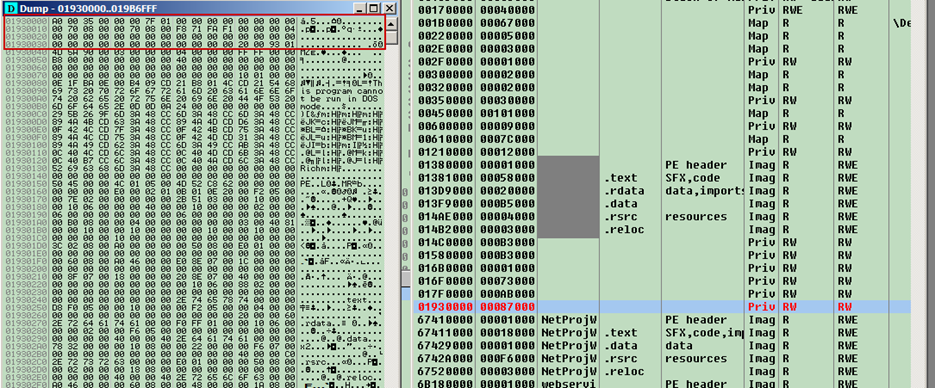

Obscure dump

After the stage of evasion techniques is successfully passed, the Black Basta dropper has one more trick up its sleeve. The Black Basta payload is not simply unpacked and executed in memory; there is data located before the PE header of the ransomware to prevent automatic scanners from easily identifying the malicious payload.

Figure 6 – Data located before a PE header to prevent automated memory analysis.

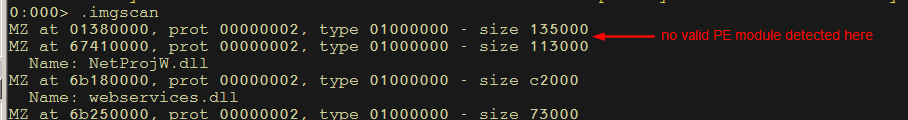

As expected, the.imgscan command in WinDbg fails to reveal the Black Basta PE module in the dropper’s process memory.

Figure 7 – Missing Black Basta module in WinDbg memory scan.

After all these steps are passed, the actual Black Basta payload is executed.

Black Basta payload

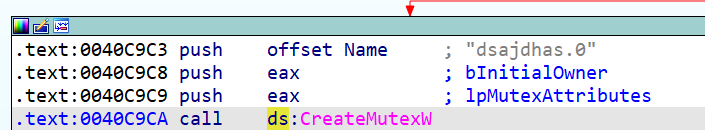

A mutex is created at the start of the ransomware execution to ensure only one copy of the malware is active:

Figure 8 – Mutex creation in Black Basta.

In the sample we describe, the mutex name is “dsajdhas.0”.

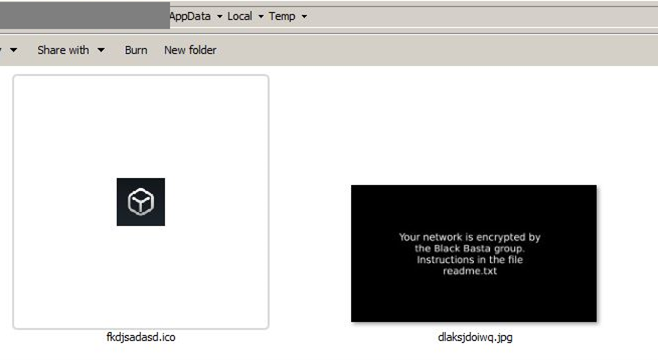

The malware then sets the wallpaper and assigns a custom icon to the files with the “.basta” extension.

Figure 9 – Images dropped by Black Basta.

The images are taken from TEMP directory where Black Basta unpacks them.

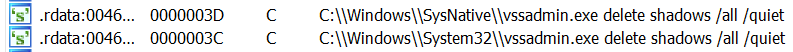

The ransomware also attempts to delete any shadow volume copies as shown in the image below:

Figure 10 – Commands executed to delete shadow volume copies.

Encryption

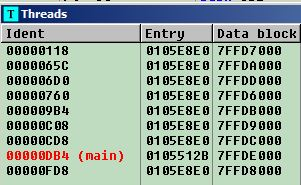

Multiple threads are created to make a multi-threaded encryption process:

Figure 11 – Threads created to perform encryption.

The malware encrypts all the files found on the drives except for the ones that have the following strings in their paths:

- $Recycle.Bin

- Windows

- Documents and Settings

- Local Settings

- Application Data

- txt

- Boot

- txt

- jpg

- DAT

- ico

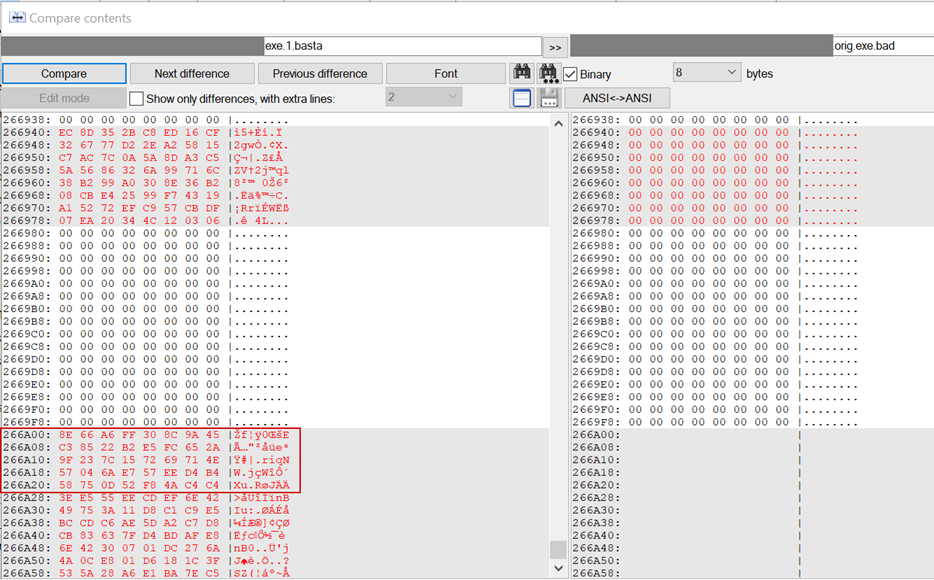

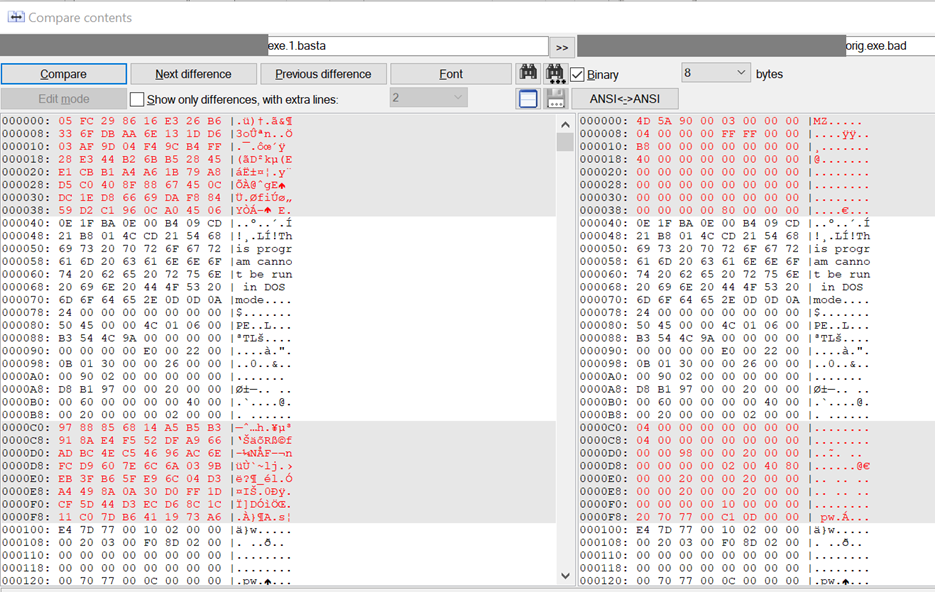

ChaCha20 stream cipher (which as reported in independent research is faster than AES) is used for encryption with a key generated randomly for each encrypted file. This key is then passed to the RSA encryption with a hardcoded public key to retrieve 512 bytes of the encrypted ChaCha20 key. This key is appended to the end of the encrypted file:

Figure 12 – Start of the encrypted key at the end of the file (to the left); original file (to the right).

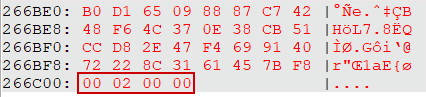

At the end of the block, there is also the length of the encrypted key (0x200):

Figure 13 – The length of the key at the very end of the encrypted file.

Note that not the entire file is being encrypted. The malware aims at each third block of 64 bytes:

Figure 14 – Blocks encrypted by Black Basta (to the left); original file (to the right).

To process a file, the usual kernel32 functions are used:

- CreateFile

- ReadFile

- WriteFile

- MoveFile (to rename an encrypted file)

As a side note, we need to mention that mini GMP implementation of the RSA is used.

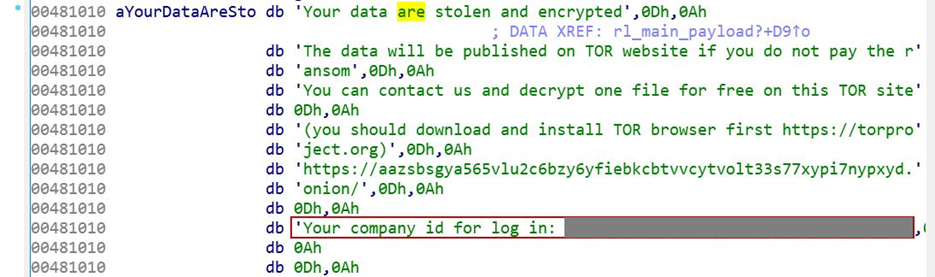

After the encryption is finished, the ransomware drops a ransom note in a “readme.txt” file on the Desktop. A company ID is hardcoded into the ransom note, which is a sign of a targeted and prepared attack:

Figure 15 – Company ID as hardcoded inside the sample.

There is no apparent way to decrypt the files without knowing the RSA private key.

Automatic distribution

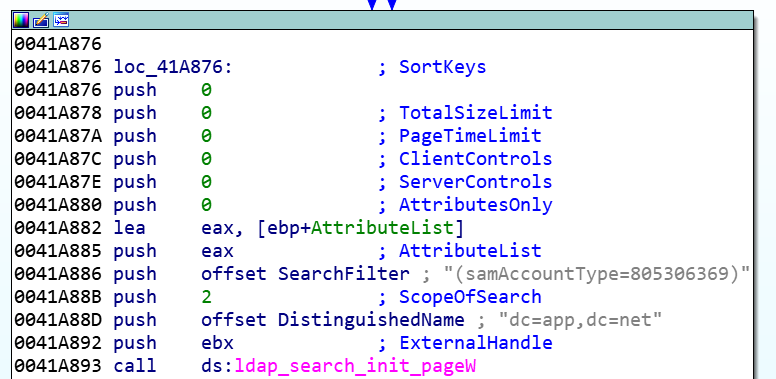

Black Basta has a built-in functionality of automatic distribution in the network, in case the droppers’ functions are not sufficient for the task. The ransomware tries to connect to AD with the help of LDAP API and iterates over the connected workstations using the filter string (samAccountType=805306369):

Figure 16 – Function to initiate a search through connected workstations.

After the list of workstations is obtained, the ransomware tries to copy itself to the remote machines via the path \\c$\\Windows\\tmp.exe. Then, with the help of the COM objects objectIWbemClassObject (CLSID: 4590F812-1D3A-11D0-891F-00AA004B2E24) and IWbemServices->Win32_Process, the executable copied in the previous stage is launched via the Create method.

Conclusion

Ransomware attacks are one of the most serious threats a victim may face. Contemporary ransomware attacks have a record of numerous successful extortions, and can move laterally within a network, thereby resulting in more and more guaranteed rewards when using a double extortion scheme.

Newly emerged Black Basta is an already successful ransomware player, which takes various precautions and the actual data encryption is performed, as exemplified by the anti-debug and evasion techniques applied. The combination of soft and technical skills exhibited by the Black Basta gang, when successfully applied in a ransomware attack, can lead to truly devastating results.

As seen in the article, not only is the ransomware itself engineered to inflict maximum damage in the least time possible, but the delivery stage is also stealthy, sophisticated and effective. Black Basta knows without a doubt that the environment is safe and has a clean shot to perform the encryption.

To lower the chances of being victimized by this and similar attacks, employers should adopt the following practices:

- Educate your employees on how to stay safe in the cyber security sphere.

- Do not open non-corporate attachments from unexpected senders.

- Update and improve the security of your cyber infrastructure.

- Make regular backups of the sensitive data and store them on external drives.

- Keep your systems up-to-date with the latest updates available.

Check Point’s Anti-Ransomware, protects organizations from the most sophisticated ransomware attacks, including Black Basta, and safely recovers encrypted data.

Anti-Ransomware is offered as part of Harmony Endpoint, Check Point’s complete endpoint security solution. Harmony Endpoint provides comprehensive endpoint protection at the highest security level.

Check Point Protections

Ransomware.Win.BlackBasta.A

Ransomware.Win.BlackBasta.B

IOCs

07fdfcde9c9a3f60b1302c6a42ef1191fcfa861e94638968c8023ed957d9144f

5d2204f3a20e163120f52a2e3595db19890050b2faa96c6cba6b094b0a52b0aa

5d2204f3a20e163120f52a2e3595db19890050b2faa96c6cba6b094b0a52b0aa

7883f01096db9bcf090c2317749b6873036c27ba92451b212b8645770e1f0b8a

ae7c868713e1d02b4db60128c651eb1e3f6a33c02544cc4cb57c3aa6c6581b6e

b1773d41cb87d61073f7bb1fc3aca877f01fd64f7b1430666ce3c9bb65ecae70

bc1baf6014affceab4e59a781c33df25f2e9baa17c0cc579f6a6702d0db585d2

e354bf321585aef56829913384ff890deb5836ce1299fb27d7d34b4dab37b937

Sources

- Check Point Threat Report after H1 2022// https://blog.checkpoint.com/2022/07/26/check-point-research-weekly-cyber-attacks-increased-by-32-year-over-year-1-out-of-40-organizations-impacted-by-ransomware-2/

- Leaks of Conti Ransomware Group // https://research.checkpoint.com/2022/leaks-of-conti-ransomware-group-paint-picture-of-a-surprisingly-normal-tech-start-up-sort-of/

- Anti-Debug Encyclopedia // https://anti-debug.checkpoint.com/

- Evasions Encyclopedia // https://evasions.checkpoint.com/

- Can You Trust a File’s Digital Signature? // https://research.checkpoint.com/2022/can-you-trust-a-files-digital-signature-new-zloader-campaign-exploits-microsofts-signature-verification-putting-users-at-risk/

- What’s the appeal of using ChaCha20 instead of AES? // https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/34455/whats-the-appeal-of-using-chacha20-instead-of-aes