Introduction

You’ve probably heard of the Conti ransomware group. After their 2020 emergence, they’ve accumulated at least 700 victims, where by “victims” we mean ‘big fish’ corporations with millions of dollars in revenue; unlike your average neighborhood ransomware operation, Conti never cared for extorting your mother-in-law for her vacation photos. For a while, Conti was the face of ransomware, along with fellow gang REvil – until this February, when 14 REvil operatives were arrested by the Russian authorities, leaving Conti effectively alone in its position as a major league ransomware operation. At the time, this was cautiously hailed as a sign of goodwill on Russia’s part; some figured that possibly the Russians would finally refuse to tolerate the incessant and irreverent attacks originating on Russian soil and targeted at western corporate offices, schools and hospitals. Now, a month later and two weeks into the full-blown war between Russia and Ukraine, this utopian vision does not seem so likely.

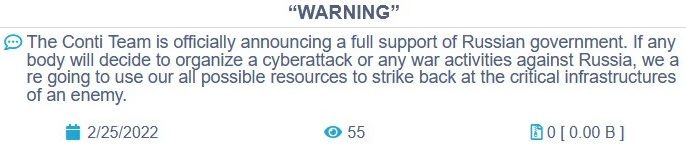

On February 25th, 2022, Conti released a statement of full support for the Russian government — coupled with a stern warning addressed at anyone who might consider retaliating against Russia via digital warfare.

Figure 1 – Initial announcement of Conti group supporting Russia

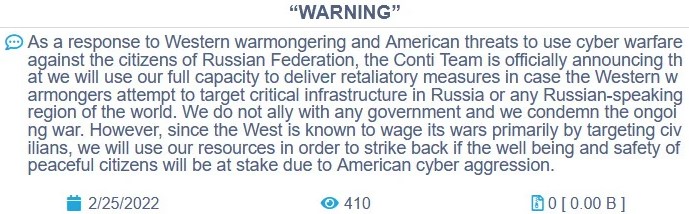

A few hours later, someone high up the chain at Conti must have realized that this statement might possibly backfire, and it was modified to read as follows:

Figure 2 – Modified announcement of Conti group supporting Russia

As per Dr. Maya Angelou’s famous quote, “When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time”. A lot of people were angry, and didn’t care for the clarification. To Conti’s dismay, one of these people had the means to meaningfully act on their anger.

Starting February 27, a new Twitter account appeared by the name of “ContiLeaks”, and started doing unto Conti as they often did unto corporations who won’t pay up. Allegedly a Ukrainian security researcher, ContiLeaks published a huge log containing hundreds of thousands of Jabber and Rocket.Chat messages that Conti had used for internal communication. This led to a veritable gold rush of researchers diving into the huge pile of messages and sharing their summaries, findings and observations; we’d be remiss not to mention the in-depth series of blog posts published by Brian Krebs, who read the entire leak and distilled it into a list of takeaways – a sacrifice that must not be taken for granted.

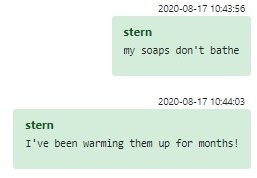

We say that because the data-set in question is simply maddening to wade through. First of all, as noted above, it is huge. Once you get past that, there are many other problems. Some of the messages are missing. Some of the messages are unclear. Some of the messages were encrypted with OTR (Off-the-Record Messaging). Some of the messages contain Russian slang that does not survive automatic translation — such as the below conversation which was, originally, about email address blacklisting evasion:

Figure 3 – Example of how tricky is Russian slang for automated translation tools

That first message feels like it should lead to a punchline a la “my dog has no nose”, but all it leads to is frustration and sadness on the part of the analyst reading it – as do many other similar messages. Still, with all the above said, these messages offer an unprecedented insight into the operations of the Conti Corporation. And it is a corporation, for all intents and purposes; there’s an HR department, a hiring process, offline office premises, salaries and bonus payments. If it weren’t for the looming threat of prison, you could mistake Conti for a normal tech startup. In this article, we delve into the inner workings of the surprisingly startup-like Conti group.

Teams and responsibilities

Conti’s structure is almost a classic organizational hierarchy, with team leaders who report to upper management, but to their credit there are many instances of different groups working with each other directly (this is called “horizontal information flow”, and is a Good Thing and a sign of organizational health, as any steeple-handed thinkfluencer will happily tell you).

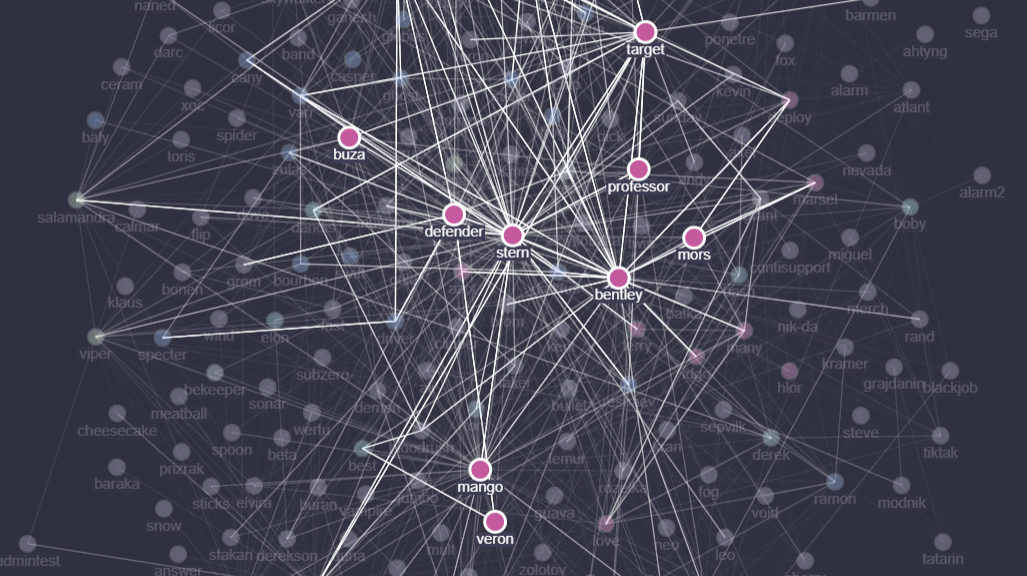

To give an overview of how the communications between the members and affiliates work, we tagged most of the active members from Jabber chat with their professional occupations and visualized their communications. In this graph, the more saturated the link between the members indicates more intensive communication, thus showing both vertical linkage between the bosses and subordinates, and horizontal linkage between the members actively working on shared projects. This however is by no means a perfect representation of the organizational structure, as people are being replaced and promoted all the time.

Graph tips & notes:

- Drag a user node to see their connections and the amount of messages they sent to other users.

- Hover over the legend’s colors, to see the cluster of people with similar roles within the organization.

- Users who had less than 10 incoming and outgoing messages were filtered out of the graph.

- Due to the usage of encryption services, some conversations are missing messages.

The main groups we observed were:

- HR – Responsible for making new hires. This includes combing through Russian-speaking job searching sites, organizing online interviews, and mediating between the interviewer and the relevant technical focal point. In many cases, HR did not have the authority to decide on compensation; if an interview went well, the candidate would be referred to higher management who would make them an offer.

- Coders – The celebrated folk who maintain the nuts and bolts of the actual malware code, the server back-ends, and admin web panels required by the Conti group’s day-to-day operations. This extends to many auxiliary tools used by the Conti group including TrickBot, Bazaar, Anchor, the C&C infrastructure and, of course, the “lockers” themselves that encrypt the files of unfortunate victims.

- Testers – Check various malware against known security solutions to make sure that they avoid detection. Understandably, security vendors aren’t thrilled to sell their products to the Conti group — in at least one case a third party had to get involved, and make the purchase on Conti’s behalf (while collecting a hefty premium), and we imagine this was a normal occurrence.

- Crypters – “Crypting” is cybercrime slang for what some of us more academic types call “obfuscation”. Crypters are tasked with making syntactic changes to payloads, binaries and scripts to make them more difficult to detect and analyze while preserving their semantic function. Crypters would often work closely with testers; crypter strategies could look good in theory, but the real test was when a tester would throw them against a hostile sandbox.

- SysAdmins – Conti members tasked with setting up the attack infrastructure and providing support as necessary. This includes all tasks dealt with by a typical IT department — installing panels, maintaining servers, erecting proxies, registering domains, managing accounts, and presumably telling other Conti members to try turning off their machines and turning them back on again.

- Reverse Engineers – Look at existing tools in order to understand how they work. For instance, while the Conti locker was being built during mid-2020, its development was supported by a reverse-engineering effort of the Maze ransomware, which was being used at the time by some of Conti’s affiliates. Another example is a project reversing the Buer loader in order to launch a similar project inside the Conti ecosystem.

- Offensive Team – Given initial access to a victim machine, these Conti members (called “hackers” and “pentesters” in communications) are responsible for privilege escalation and lateral movement, converting an initial breach into a full capture of the targeted network. Their ultimate goal would be to obtain domain administrator privileges, which would then allow exfiltrating and encrypting the victim data.

- OSINT Specialists and Negotiation Staff – Once a victim’s data is successfully held for ransom, these Conti members step in to make demands and attempt to secure a deal. Some are OSINT specialists, conducting research on the targeted company — the sector it operates in, its annual revenue, and so on, in order for the ransom payment demand to strike a balance between lucrative and realistic. Other members do the actual negotiation, and act as “customer service representatives” operating Conti’s Tor-based chat. Handling “customers” would often entail coaxing, making threats, or providing proof that Conti possesses the exfiltrated data and can recover it for the victim or publish it, depending on whether the victim pays. Management of the Conti leaks blog, and scheduling publication of victim data in case the deadline for ransom payment is not met, also falls under this department’s purview.

From the graph we can also identify the main people in the organization playing the key role in the group’s communications:

Figure 4 – Key members and their communications based on the leaked messages

Figure 4 – Key members and their communications based on the leaked messages

- Stern is the Big Boss, well-known as a leader of the group both internally and outside the organization. He’s the one developing the high-level vision of the group’s operations and collaborations with affiliates, and manages many of the people and projects directly and indirectly. Stern also directly pays salaries to multiple members of the organization and manages most of the expenses. Depending on time, Stern’s management style fluctuates widely between micromanagement with sending broadcast messages asking about their tasks and problems and multi-day absences.

- Bentley is a technical lead of the group responsible for testing and evasion of malware and payloads used by multiple groups inside and outside the organization. Bentley manages teams of crypters and testers, working with many different internal and external customers, as well as handles the questions related to digital certificates, third-party anti-virus solutions.

- Mango is the “manager of general questions of the team”, solving mostly the questions between the people who are responsible for infection campaigns and the coders. Mango also takes part in the HR process and directly pays salary to part of the task force, as well as effectively assisting Stern with his other projects.

- Buza is a technical manager responsible for coders and their products, curating loaders and bots development within multiple coders teams.

- Target is a manager responsible for the hackers’ teams, their intercommunication and workload. He also manages all the aspects of all offline offices, both for hackers and operators, their budgeting, HR and effective communication with other parts of the organization. He also manages part of the tasks related to social engineering campaigns.

- Veron aka mors is the focal point of the group’s operations with Emotet. Veron is managing all the aspects of Emotet campaigns, including their infrastructure, closely with relevant Conti members.

Hiring process

We’ve all heard of the skill shortage in tech, and the Conti group has to deal with it just like everyone else. To improve their odds, they opted to diversify their initial candidate pool; instead of solely relying on criminal underground talent, Conti regularly recruits staff by abusing legitimate recruitment websites.

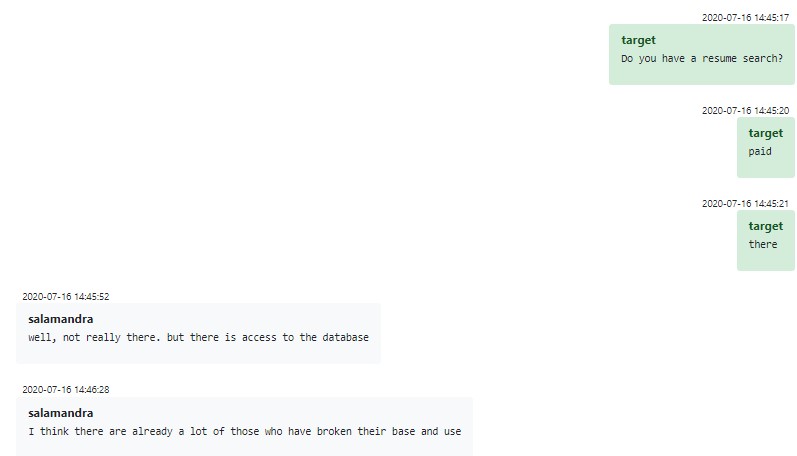

Recruitment Sites

The main resource typically used by Conti HR for hiring is Russian-speaking headhunting services such as headhunter.ru. They’ve also used other sites such as superjobs.ru, but reportedly with less success. Conti OPSec forbids leaving traces of developer job openings on such websites, a regulation stringently enforced by one of the higher-ups, Stern; and so for hiring developers, Conti bypasses the headhunter.ru job system, instead directly accessing the CV pool and contacting candidates by email. You might wonder “why does headhunter.ru offer such a service?”, and the answer is, they don’t. Conti simply bought the software which provide access to the “borrowed” CV pool without permission, which seems to be standard practice in the cybercrime world.

Figure 5 – Access to headhunter.ru resume database through third-party tools for the recruitment purposes

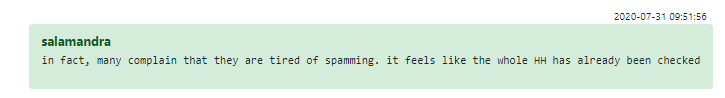

This need to directly interface with a huge list of CVs instead of using the site’s built-in filtering further exacerbates the typical HR struggle to find candidates with the relevant tech expertise. At times, Conti HR has expressed downright frustration at being swamped with irrelevant candidates:

Figure 6 – Challenges in finding talents for Conti Corporation

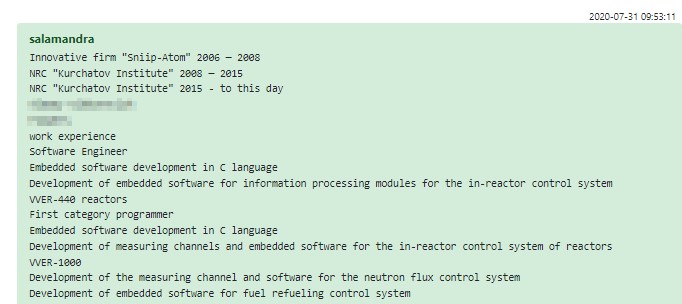

Once HR does locate a candidate who might fit some vacancy inside Conti Corp, their CV is anonymized and sent to the relevant technical point of contact inside the organization. This begins a cumbersome dialogue where HR acts as a mediator, to make sure that the candidate’s prospective superior does not learn their identity. Needless to say, this process is not bulletproof. Sometimes it’s possible to deduce the candidate’s identity by running a web search for their job experience, and sometimes HR would just make a mistake and fail to expunge the name.

Figure 7 – CV of one of the candidates passed from HR to the hiring manager

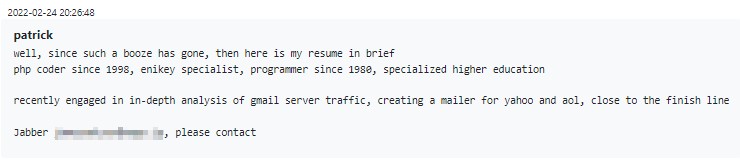

One might be surprised by the demographic make-up of Conti employees. Contrary to the prevailing stereotype of young and reckless cybercriminals, who have an illusion of invincibility and nothing to lose, Conti was also approached by prospective senior employees. One such person, who claimed to have developer experience going back to 1980, introduces himself as follows:

Figure 8 – Old school developer working for the group

The use of HeadHunter as a recruiting tool is not limited to technical specialists. It was also used for recruiting other employees, e.g. dispatchers for call centers used in social engineering campaigns such as BazaarCall. Interviewing these candidates is the responsibility of “Derek”, a Conti HR employee, who’d use Telegram instead of tor-based chats for this task.

Word of Mouth

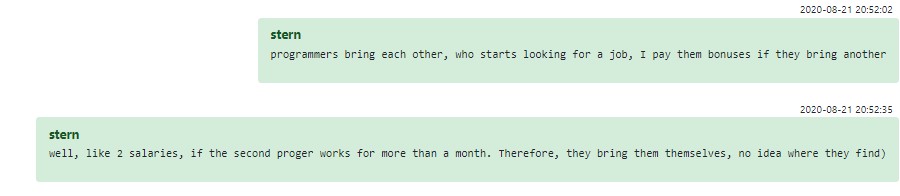

When communicating with employees, higher management would often make the case that working for Conti was the deal of a lifetime — high salaries, interesting tasks, career growth(!) — and employees should make an effort to pull in any highly-talented candidates they know, so that they may also enjoy this paradise. “Stern”, one of the higher-ups, even came up with an employee referral program for coders, where a successful referral that lasts more than a month nets a bonus equal to the referred employee’s second salary.

Figure 9 – Refer-a-friend bonuses

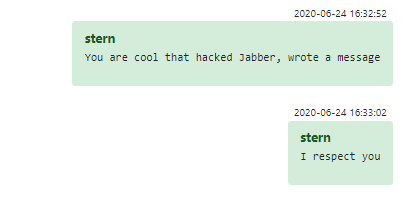

In one truly outstanding case, a curious ex-red teamer hacked the group’s Jabber in order to speak to Stern directly. While in a typical tech company such a gambit might be frowned upon, in the cybercrime world it is evidently an equivalent of the mythical Firm Handshake:

Figure 10 – Ex-red teamer hacked the group’s Jabber to get the job later

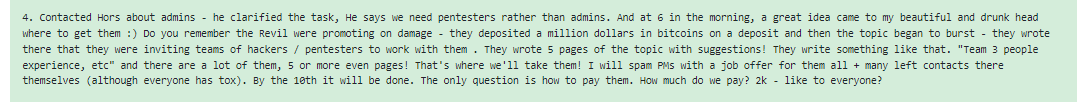

Darknet Forums

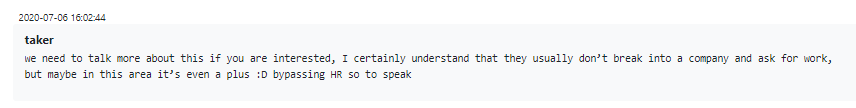

Apart from these unorthodox methods, Conti also recruits talent in the more traditional way, through underground forums. Prospective candidates are first given the jabber handle that their interviewer will use (such as admintest, which would handle tests for sysadmins). If the interview was successful, a permanent account for the candidate is created. Even with this routine method, Conti HR would sometimes get creative: for example, when searching for offensive team members and sysadmins, they came up with the idea of “recycling” an older recruitment drive by a rival ransomware group. Their chief competitor, REvil, had earlier pulled a publicity stunt and deposited a million dollars in bitcoin into an account, then posted a recruitment ad in the midst of the very active forum thread discussing the deposit. This ad received many responses with contact details, all public, and so Conti HR could extract from this thread a pool of high-quality candidates to spam with job offers.

Figure 11 – Borrowing talents from REvil group thread on the dark forum

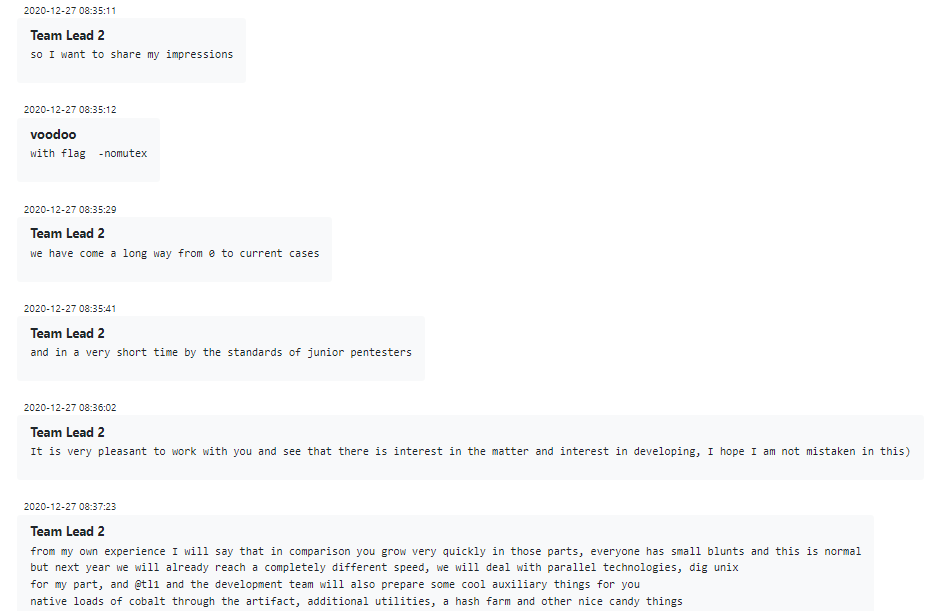

Compensation and Performance

Members of Conti’s negotiating team (including OSINT specialists) are paid by commissions, calculated as a percentage of the paid ransom amount that ranges from 0.5% to 1%. Coders and some of the managers are paid a salary in bitcoin, transferred once or twice a month.

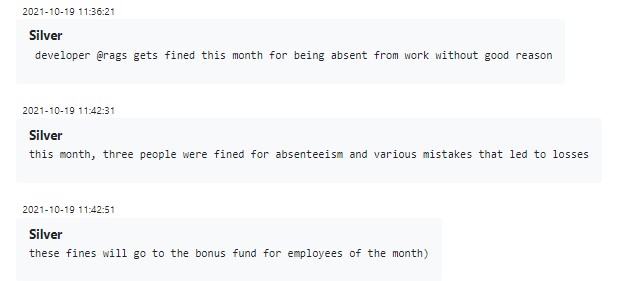

Conti employees are not protected by their local labor boards, and so have to endure some practices that typical tech employees are exempt from, such as being fined for underperforming:

Figure 12 – Fines for underperformance

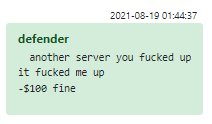

While fines are mostly used as an established tool in the coder department, they are sporadically employed on manager whims in other departments — for example, in IT and DevOps, where one person responsible for depositing money was fined $100 for a missed payment:

Figure 13 – Fines for technical mistakes

Figure 13 – Fines for technical mistakes

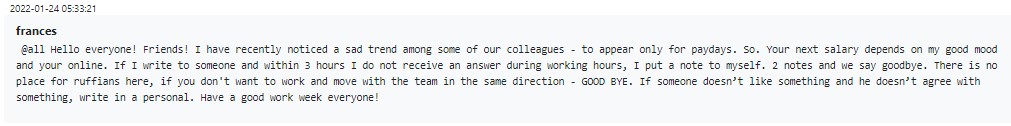

Ultimately, this method proved not effective enough, and Conti management had to resort to the more traditional threat of termination in order to motivate employees, as seen below.

Figure 14 – Termination for non-motivated employees

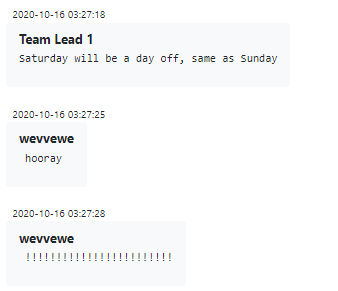

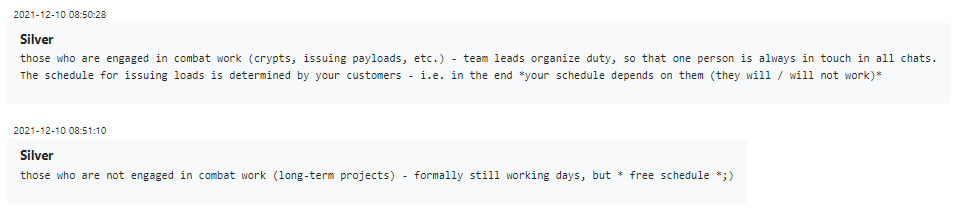

The Offensive team gets less flexibility in its time off as well. After all, a team member being available or not can spell the difference between a breach being detected and neutralized, and it being successfully advanced to the stage where victim data is encrypted and exfiltrated. For members of this team, who are used to being constantly on call, a simple pleasure such as having Saturday and Sunday off is cause for celebration:

Figure 15 – No work-home balance for some of Conti employees

Other than these strokes of good fortune, the offensive team cannot catch a break. Even on the New Year, which is widely celebrated in all Russian-speaking countries and usually entails several days of employee vacation, members of this team are expected to jump into their “combat roles” if need be. Other employees are also technically on call during these days, but it is strongly implied that they are on paid vacation in practice, and will not be getting bosses’ surprise inspection texts during the holiday.

Figure 16 – Conti employees are entitled to be available for work even during the New Year holidays

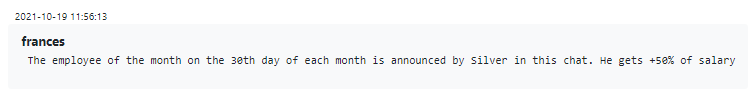

As seen in Silver’s message further above, there is an “employee of the month” award that draws from the fund of punitive fines levied on that month’s less favored employees. The award bonus is equal to 50% of that employee’s salary, and may be given to employees for useful new initiatives that score points with management (such as inventing a new payload delivery method) or for extraordinary commitment and persistence while solving some specific issue.

Figure 17 – Employee of the month competition

Management evidently takes the award very seriously — the reasons for picking the winner are not made up, and the above-mentioned points do matter.

Figure 18 – How the managers chose the employee of the month

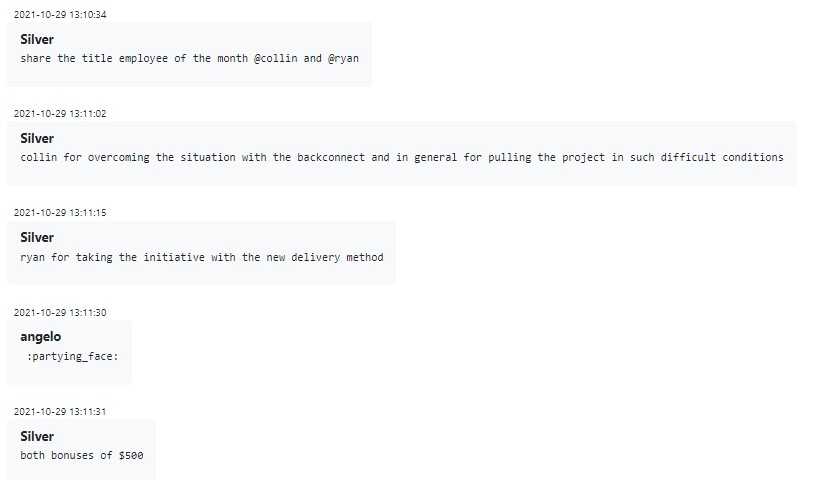

Management style varies from team to team. In some cases, the “big boss” Stern just sends a broadcast message asking the group how they are, what projects they are working on and whether they have any new ideas they want to advance. In other cases, middle management is involved and typically demands reports, most of which are unfortunately unavailable to us as they are transferred with OTR or via private sharing services such as privnote.

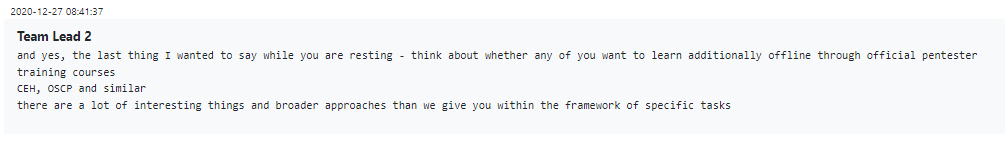

At times team leaders might even engage in the time-honored corporate tradition of the Performance Review, discussing at the end of the year how the employee fared, what they did right and how they can improve, as well as informing them about Conti’s global plans for next year and recommending training opportunities.

Figure 19 – “Performance review” and official trainings for Conti employees

Remote and Anonymous Work

Not all Conti employees know that they are part of criminal activity — at least not right from the start. In one online job interview, a manager tells a potential hire for the coding team: “everything is anonymous here, the main direction of the company is software for pentesters”.

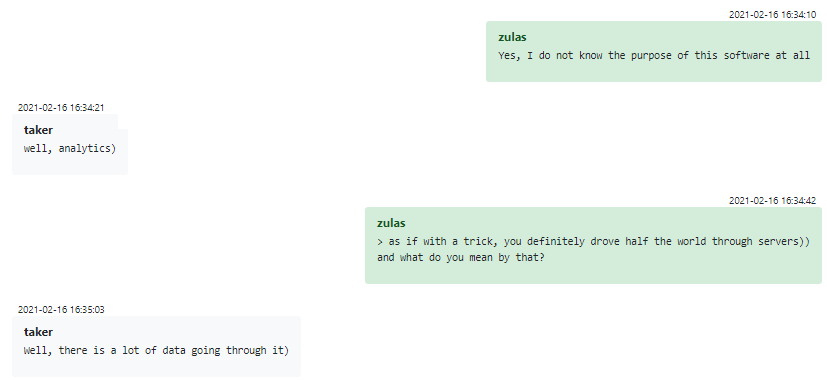

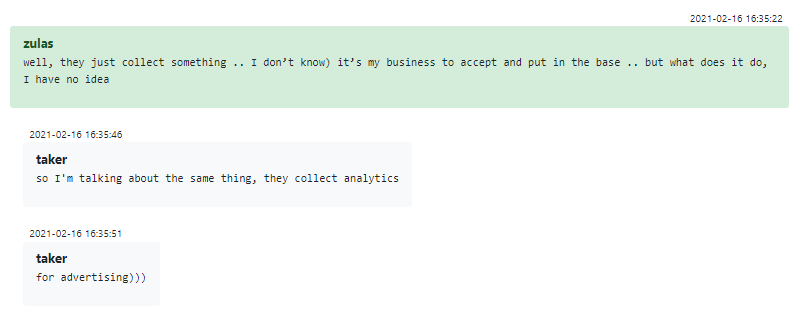

One striking example is a group member known by the moniker “Zulas”, most likely the person who developed Trickbot’s backend in the Erlang programming language. Zulas is very passionate about Erlang, eager to show examples of his other work, and even mentions his real name. When his manager mentions that his “trick” (Trickbot) project was seen by “half of the world”, Zulas does not understand the reference, calls the system “lero” and reveals that he has no idea what his software is doing and why the team goes to such lengths to protect member identities. His interlocutor decides not to break his naive heart, and tells him that he is working on a backend for an ad analytics system.

Figure 20 – Trickbot backend developer allegedly doesn’t know what he develops

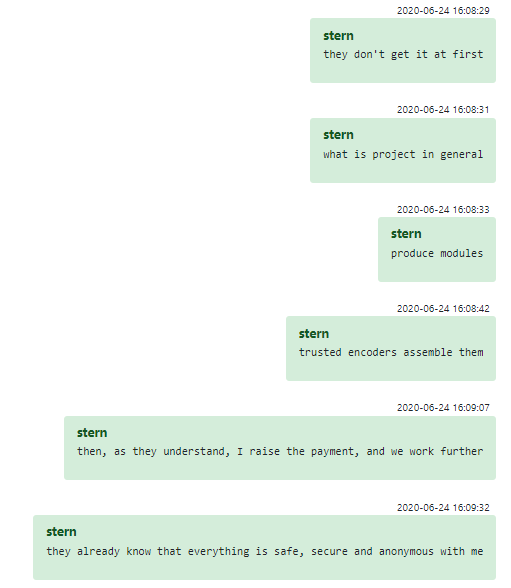

Even when an unwitting employee finally realizes what they are building, Conti has a plan to retain them. Stern himself briefly describes the process in another conversation: the coder might work on just one module, without understanding the project as a whole; when they finally realize, after many hours of work, Conti offers them a pay raise. Stern testifies that by that point, employees typically figure that since everything has gone smoothly so far, they don’t have to worry about consequences, and therefore the only incentive to go through the hassle of quitting their job is purely moral considerations. Stern seems to imply that this method yields good retention rates, even for employees who would otherwise have balked at being recruited to work for a cybercrime syndicate in the first place. If you ask us, this ranks right up there with Asch’s and Milgram’s experiments as a depressing empirical result in social psychology.

Figure 21 – What Conti developers know about what they are doing?

At Conti, We Work Hard and Play Hard

It seems that many of the long-term employees developed relationships that extend further than just anonymous communication via work chat. For example, some employees are comfortable with lending other members money if they are stuck in another city and forgot their ledger. Some members even have face to face meetings, getting together and drinking wine with their families:

Figure 22 – Relationship between some Conti employees

An inherent part of belonging to a crime group, and a natural conversation subject between colleagues, is the job risk. Attitude to this subject varies greatly between employees: some disregard the risk and see mainly the benefits, going so far as to romanticize their job (“only here I realized the dreams can come true”), and others express fear and even outright confess that they want out.

Figure 23 – The realization of what the group is doing

Offline Offices

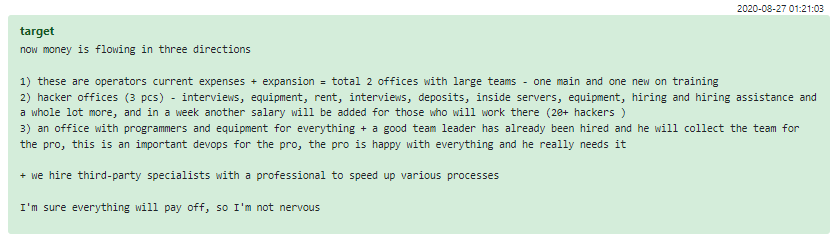

You’d imagine an enterprise like Conti would be hosted entirely online, but no: the Conti group holds several physical offices. These are curated by “Target”, Stern’s partner and effective head of office operations, who is also responsible for the wage fund, office technical equipment, the Conti hiring process and personnel training. During 2020, offline offices were mainly used by testers, offensive teams and negotiators; Target mentions 2 offices dedicated to operators who are speaking directly with victim representatives. In August 2020, an additional office was opened for sysadmins and programmers, under the purview of “Professor, who is responsible for the whole technical process of securing a victim infection

Figure 24 – Expenses in Conti Corporation

The leaked Rocket.Chat messages include the communications of the offensive team members who worked at the office, indicating that the Rocket.Chat was likely installed on their mobile devices.

Figure 25 – Office day to day of Conti Corporation

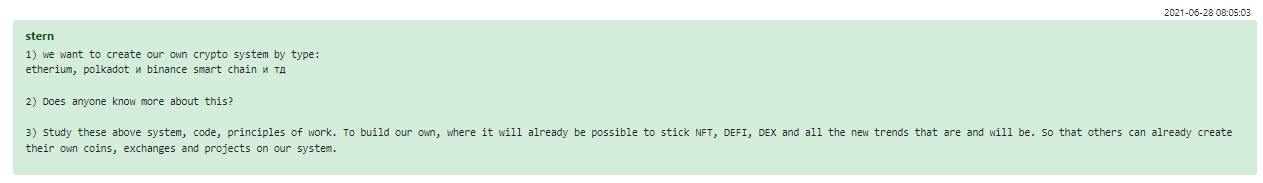

Future Development Plans

Conti higher management constantly seeks new ways to expand the business. The ideas floated for this purpose range from simple scams to full-scale side projects. One of the ideas discussed was creating a crypto exchange in the group’s own ecosystem:

Figure 26 – “Crypto System” plans by Conti group

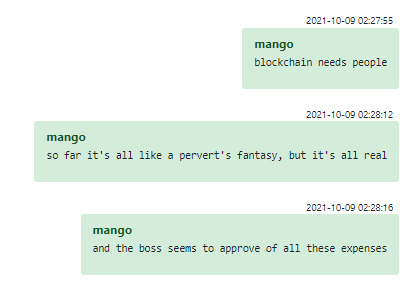

Mango seems to enthusiastically support all the boss’s ideas and promotes them among other members of the group:

Figure 27 – Internal promotion for the new crypto business ideas

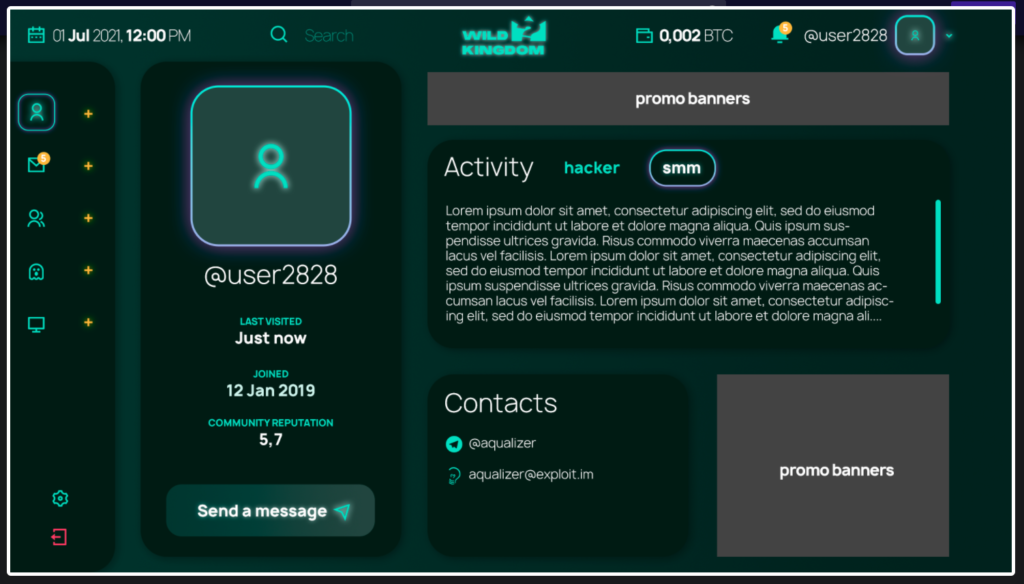

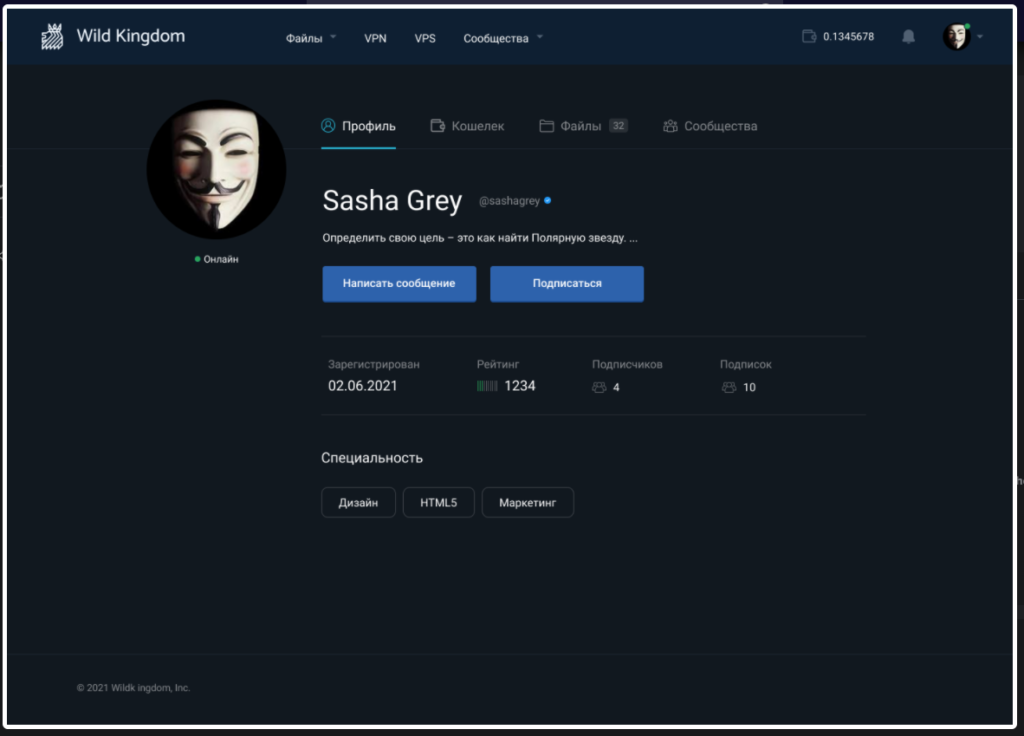

Another project is the “darknet social network” (also: “VK for darknet” or “Carbon Black for hackers”), a project inspired by Stern and carried out by Mango, planned to be developed as a commercial project. In July 2021 Conti was already in contact with a designer, who produced a few mockups.

Figure 28 – Design mockups for the new darknet social network

Aftermath of the Leak

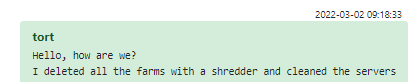

Because the leak kept going after the initial dump of leaked data, we all got the unusual privilege of seeing responses to the original leak. Members were seen wiping past activity, removing production VMs and moving to other communication channels.

Figure 29 – Cleaning the production VMs after the leak

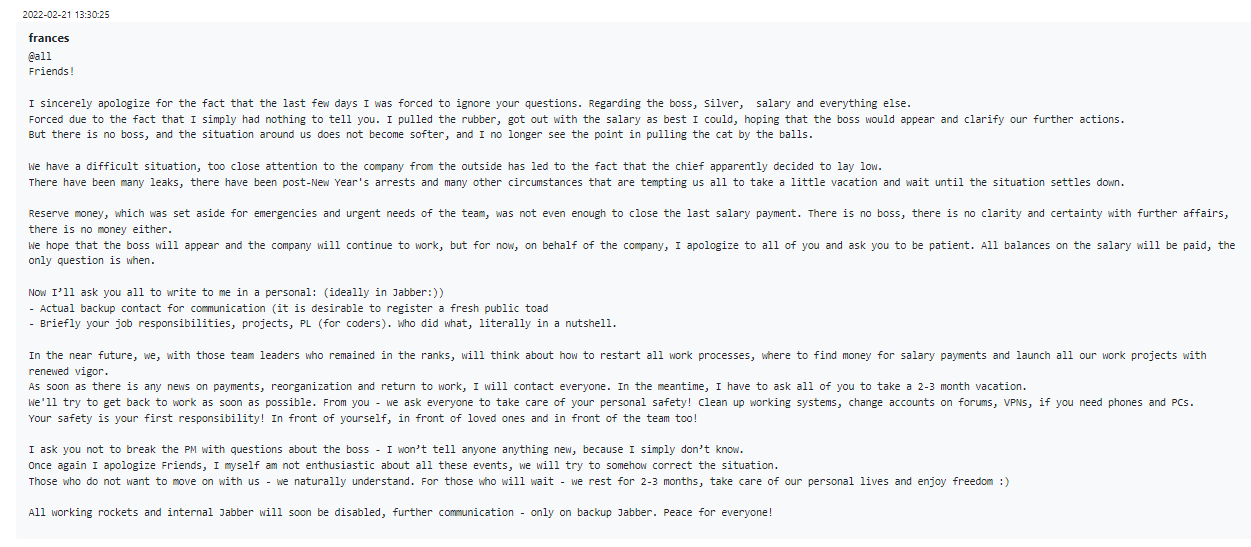

It seems the leak added to the pile of current problems in Conti. As we saw in the chats, the big boss Stern went silent around mid-January, in January-February there we’ve observed multiple reported issues with the salary, and eventually, a few days before the leak Frances in Rocket.Chat tells everyone to take a break for 2-3 months to regroup and reorganize due to wide public attention and the absence of group’s bosses.

Figure 30 – Notification in Rocket.Chat regarding the suspension of operations

While all this is going on, the Conti business remains operational, at least partially. The Conti leak site (ContiNews) is still up and keeps being updated with new victims. As the process of the setup and support of Conti infrastructure is streamlined, it won’t be too much of a problem for Conti to set up its operations from scratch.

As for members, Conti will in all likelihood lose a few. Certainly, those members who were doxxed as a result of the leak are expected to at least take a long vacation. Probably several more employees who were offended by the way other members talked about them behind their backs will leave, as well as those who were already uneasy about the potential occupational hazards of working for a ransomware operation; this ongoing leak no doubt spooked them.

Having said all that, with all the knowledge, effort, organization, ingenuity and money poured in, Conti is simply Too Big To Fail. Barring a wide-sweeping arrest such as the fate that befell REVil, Conti will in all likelihood rise again. If any of us had romantic delusions about a hugely profitable operation such as Conti being run by a small, clueless, passionate group that’s just “winging it” and might get tired of rolling in all this money, we all know better now.