Author: Yoav Arad Pinkas

Key Findings

- AI is already extensively utilized in election campaigns worldwide. Deepfakes and voice cloning have been employed in elections in three main venues:

- By candidates for self-promotion.

- By candidates to attack and defame political opponents.

- By foreign nation-state actors to defame specific candidates.

- Deepfake materials (convincing AI-generated audio, video, and images that deceptively fake or alter the appearance, voice, or actions of political candidates) are often disseminated shortly before election dates to limit the opportunity for fact-checkers to respond. Regulations which ban political discussion on mainstream media in the hours leading up to elections, allow unchallenged fake news to dominate the airwaves.

- Within the realm of AI-driven disinformation campaigns in elections, audio deepfakes are currently employed more extensively and successfully than those involving images and videos.

- Many countries currently lack adequate regulations and laws concerning fabricated materials. As a result, this allows the dissemination of fake audios and videos.

- In most cases, well-established, functioning democracies report fewer instances of domestic exploitation of AI-generated disinformation.

- Nation-state campaigns have the capability to distribute well-structured false narratives and synchronize broad disinformation campaigns.

- Political arenas saturated with AI-generated information products suffer from “the liar’s dividend” which allow politicians to dismiss authentic scandalous materials as fabricated.

Background

2024 is expected to be a pivotal moment for democratic processes worldwide, as over 2 billion individuals in 50 nations prepare to cast their ballots in elections. This global electoral wave includes countries such as the United States, India, Mexico, the European Parliament, and South Africa, following significant ballots already completed in Indonesia, Taiwan, and Pakistan. The collective outcome of these elections stands to critically influence the future political direction on a global scale.

This year’s advancements in the sophistication and accessibility of generative AI have heightened concerns about the integrity of the electoral process. These concerns are primarily focused on disinformation campaigns, particularly the fear that the widespread application of new technologies, capable of producing and disseminating fabricated video and audio content, could detach public discourse from its factual roots and decrease public trust in democratic institutions.

In our previous publication in September, we reviewed the threats posed by advancements in generative AI technologies to democratic elections. The article discussed how AI could generate large volumes of tailored content, making it a powerful tool in micro-targeting and behavior manipulation within the political sphere. This ability to produce personalized content on a massive scale and at a low cost coupled with its potential in producing highly realistic yet false audio-visual materials raised fears that future political discourse could divert attention from relevant political issues.

Since then, Check Point Research has revealed the trade in sophisticated tools in criminal internet markets, which incorporate AI capabilities to create deepfakes and manage social media accounts. One such platform, offered on a Russian underground forum, employs AI to automate the distribution of content via counterfeit profiles on social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook. This particular platform is capable of overseeing hundreds of accounts, facilitating daily posts, and is adept at conducting large-scale influence campaigns for elections. Additionally, multiple services specializing in the creation of deepfakes, RVCs (Retrieval based Voice Conversion) and AI-powered spam emails have surfaced, exploiting this technology to circumvent security protocols and increase their success rates in targeting individuals.

The availability of potentially malicious AI tools extends beyond Dark Web markets. A recent report by Check Point Research highlighted comparable functionalities available on open-source platforms. Specifically, over 3,000 GitHub repositories are dedicated to the development and dissemination of deepfake technology, with services offered at prices starting as low as $2 per video.

Review of AI deepfake exploitation in elections

Previous discussions of AI tool impacts on elections were mostly based on assessments of hypthetical threats. With the advent of sophisticated generative AI tools, foreign states and domestic political candidates alike are in position to exploit these technologies.

Among the most concerning are “deepfake” services, which can create highly realistic yet fake audio or visual content. These materials can be used by domestic political parties and candidates, or foreign agents, to elevate a particular candidate or party’s chances in the election, harm competitors, or just generally undermine public trust in the democratic process. On the home front, political contenders or their affiliates could utilize deepfake capabilities alongside AI-driven social media platforms to skew public opinion in their favor. The automation of content creation and the ability to manage vast networks of fictitious online personas enables a scale of influence previously unimaginable, complicating efforts to maintain election fairness and transparency.

Evidence is now accumulating of actual exploitation of AI-generated materials in elections around the globe. We reviewed 36 parliamentary, regional, presidential elections that took place in the six months between September 2023 and February 2024 and found substantial reports of AI-generated materials used in disinformation campaigns in at least 10 cases. Our review focused mostly on mainstream English-language media reports, possibly overlooking smaller countries which do not attract international media attention. Focusing on mainstream media reports also means that we would not be able to detect all AI-generated materials posted on social media but rather only campaigns that were reported as disinformation and were picked up by media outlets.

We begin with the review of our findings and follow with analysis and conclusions.

France

Senate elections in France were held on September 24, 2023, with 170 contested seats out of a total of 348. We did not locate any high-profile reports of AI involvement during these elections except for one report of a senatorial candidate from the ‘Europe Écologie Égalité’ party who admitted to using AI to enhance her portrait on her campaign poster. Though this is an anecdotal example, it highlights the use of AI-generated materials to improve a candidate’s appearance.

Slovakia

General elections in Slovakia were held on September 30, 2023, after a tightly contested battle between the SMER party, recognized for its Russia-friendly stance, and the pro-European oriented Progressive Slovakia party. Pre-election final polls showed a slim lead for SMER with 20.6% support, with Progressive Slovakia close behind at 19.8%. Merely two days before the election, a deceptive video surfaced on social media featuring a doctored audio clip allegedly capturing a conversation between a renowned journalist and Michal Šimečka, the head of the Progressive Slovakia party. In this falsified audio, Šimečka is supposedly discussing strategies to skew the election outcomes, including the purchase of votes from the country’s disadvantaged Roma population. The video spread rapidly across social networks and via email, notably shared by politicians with known pro-Kremlin affiliations and propagandist activities in Slovakia, including Štefan Harabin, the former Supreme Court President and ex-minister, and Peter Marček, a former parliament member.

Despite immediate doubts from experts regarding the clip’s authenticity, mainstream media was slow to react, severely restricted by Slovakia’s 48-hour pre-election moratorium, which mandates a halt on all election-related communication by media and political figures. The result here was actually to limit the dissemination of factual information or at least call out the deepfake. Wired also reported another fake audio recording in which Šimečka is heard proposing to double the price of beer.

Ultimately, SMER secured victory with 22.9% of the votes, while Progressive Slovakia finished in second place with 18%.

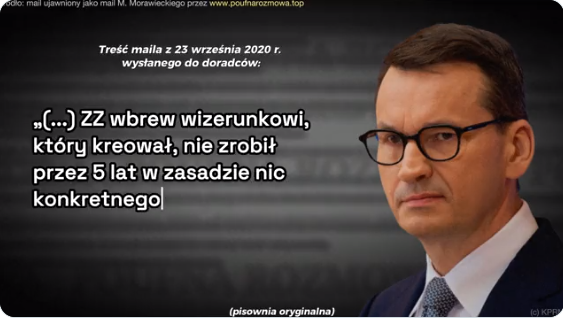

Poland

The recent elections in Poland, held on October 15, 2023, marked a significant shift in the country’s political landscape. Ending eight years of rule by the Law and Justice (PiS) party, the opposition parties secured enough seats to take power. In the weeks leading up to the elections, Poland’s leading opposition party, Civic Platform (PO), was criticized for using AI-generated audio to dub emails, which were allegedly leaked two months before the elections. The video alternated between genuine video clips and AI-generated audio of PM Mateusz Morawiecki, reading sections of purportedly leaked emails.

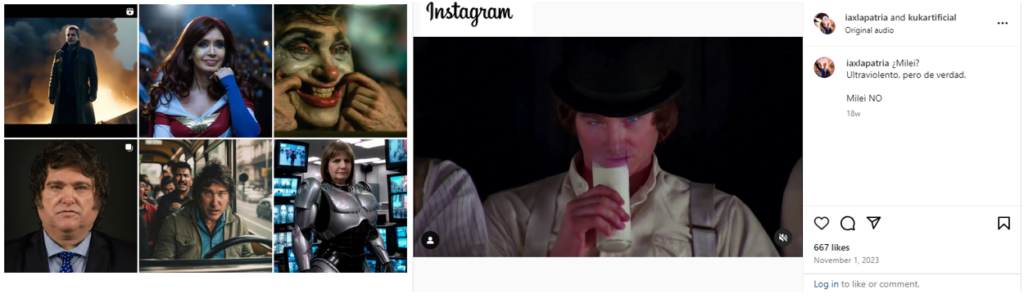

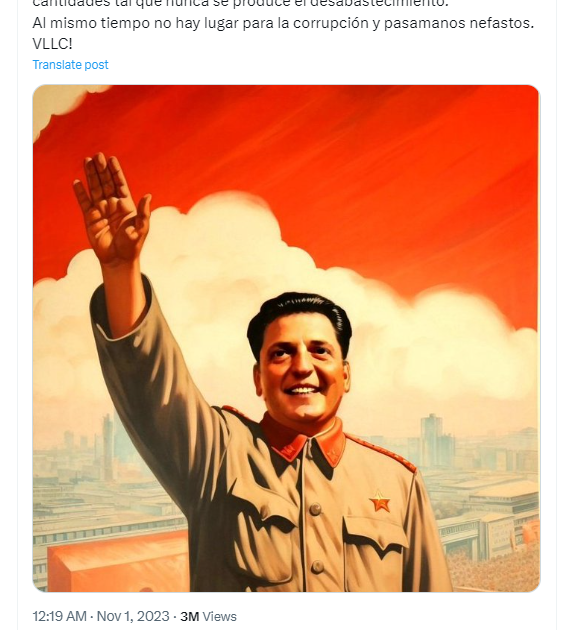

Argentina

The last general elections in Argentina, held on October 22, 2023, were significant and marked by unexpected outcomes. Javier Milei, a libertarian candidate, won the presidency in a run-off election against Peronist economy minister Sergio Massa. Milei secured almost 56% of the vote, riding a wave of discontent with Argentina’s economy, characterized by high inflation and poverty.

AI was extensively used by both main presidential candidates to create deepfakes and manipulate images for their campaigns. Sergio Massa’s team utilized AI to produce favorable deepfakes posters of himself and images of Milei in movie scenes like Clockwork Orange portraying him in a negative light as somewhat unhinged. In response, Milei’s team shared AI-generated images depicting Massa as a Chinese communist leader and himself as a cartoon lion, which gained over 30 million views. While Milei used his own X account, an unofficial account titled “iaxlapatria”, AI for homeland, was used to distribute stylized AI-generated images and video negatively portraying Milei.

Massa’s campaign said in a statement that their use of AI was meant to entertain and make political points, not to deceive. The use of AI in the Argentine elections extended to creating fabricated videos where candidates appeared to say things that they did not, inserting them into memes, and generating campaign advertisements that triggered debates over the authenticity of real videos.

While the mass AI utilization in Argentinians elections mostly demonstrates the degree to which AI tools now facilitate the creation of campaign materials which previously would have required teams of creatives and weeks of work, there were also claims of AI fabricated audio recordings. Shortly before the first round of primaries, controversial audio clips were spread on the internet. These recordings purportedly included Carlos Melconian, a candidate for economy minister, making disrespectful comments about women and proposing government roles in return for sexual favors. The authenticity of these recordings remains controversial and emphasizes another characteristic of an environment saturated with AI products – “the liar’s dividend” – which allows politicians to dismiss true scandalous materials as being fabricated.

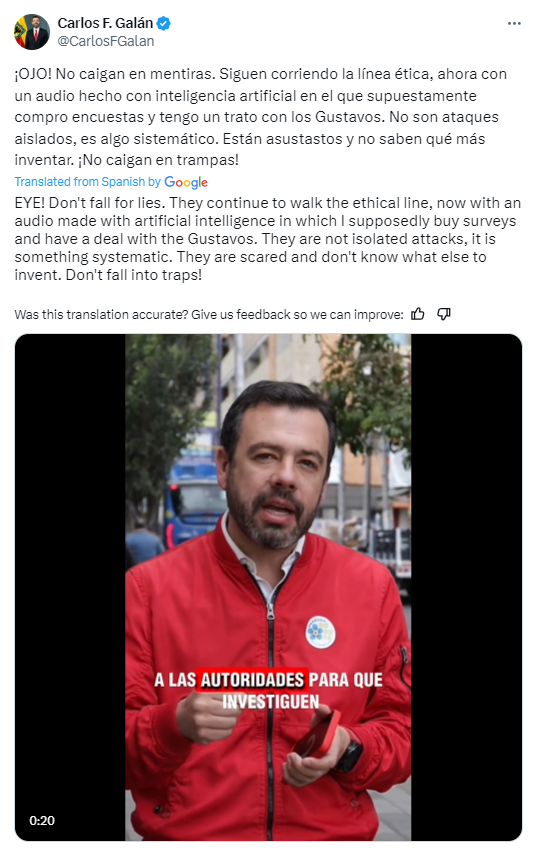

Colombia

During the October 2023 regional elections in Colombia, concerns arose about the spread of possible fake audios created through AI that targeted political candidates. Candidates Carlos Fernando Galán and Alejandro Éder, running for Mayor of Bogotá and Cali respectively, were affected by these alleged AI-generated audios shared on social media platforms. One audio clip purportedly featured Galán discussing a plan involving payments and inflated poll results to secure a spot in the second round of elections alongside another candidate. This misinformation was quickly debunked by Galán, who emphasized on X the deceptive nature of these AI-generated audios. The origin of one audio attributed to a Bogotá mayoral candidate was traced back to a TikTok account that no longer exists, raising questions about its authenticity and dissemination. Colombiacheck, a project of Consejo de Redacción, a Colombian NGO that promotes investigative journalism, analyzed the recordings and deemed them to be suspected AI deepfakes.

India

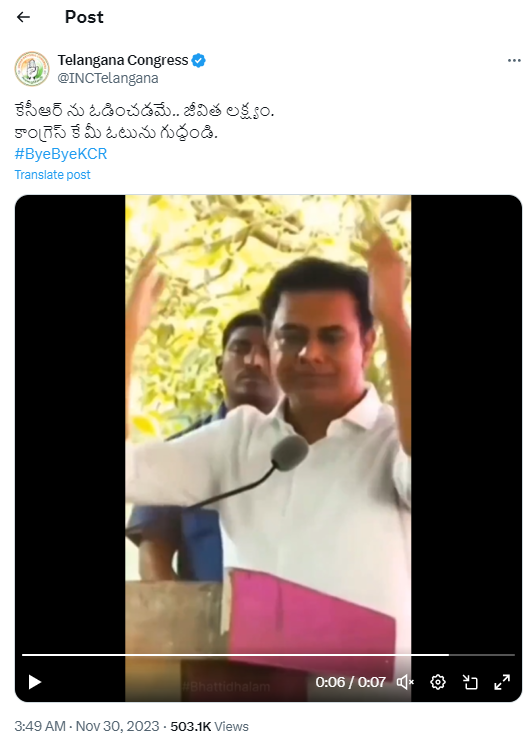

General elections in India are expected to be held between April and May 2024. In the run up of local state elections, the country was swept with reports of fake audio and video recordings which have attracted the attention of all political parties. In the earlier elections of the southern Indian state of Telangana, held on 30 November 2023, on the morning of the elections, a short video went viral on social media. The video, posted on the Congress opposition Party’s X channel, showed the leader of the ruling party, KT Rama Rao, calling voters to vote for the Congress and reached more than 500,000 views. Four months later, the post is still online.

Other reports include allegedly fake videos distributed earlier that feature local politicians in negative situations. In the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, the political campaign of the DMK party used AI to “resurrect” the long-deceased party leader, Muthuvel Karunanidhi, for at least three video speeches in which he complimented current party leaders. On another occasion, the DMK member and finance minister, Palanivel Thiagarajan, denied the authenticity of a controversial audio recording in which he accuses other party members of corruption. During the November assembly elections for the state of Rajasthan, the team of Ashok Gehlot, the Congress chief ministerial candidate, utilized artificial intelligence to create personalized voice messages, sent by WhatsApp, to greet each voter by name.

Bangladesh

The general elections in Bangladesh were held on January 7, 2024. The ruling Awami League, led by incumbent Sheikh Hasina, secured a fourth consecutive term with less than 40% of eligible voters participating. Ranking in 136th place in the V-Dem Electoral democracy index with a grade of 0.274 (out of 1), there was little doubt that Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina would be reelected. The competition between the sitting Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and the main opposition, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), was intense and divisive. Amid reports of arrests of opposition leaders and activists, and following US pressure, The Financial Times reported that pro-government news outlets promoted AI-generated disinformation. In a video posted on X, an AI-generated anchor attacks the US for interfering in Bangladeshi elections and blamed them for the political violence. Another video depicted an opposition leader suggesting his party, the BNP, should ‘keep quiet’ about Gaza to not displease the US, an opinion that could be damaging in a country with a majority Muslim population. Another fake video depicted a member of the BNP lying about his age.

Fake videos were reportedly generated using HeyGen, a US based service available for as little as $24 a month, and D-ID, an Israeli AI video service.

Taiwan

Recent elections in Taiwan brought to new heights the tensions between Taiwan and China. Lai Ching-te won the election with 40 percent of the votes, giving the DPP, which opposes China and advocates a closer partnership with the United States, a third consecutive term in office.

Among official Taiwanese accusations that China was conducting a massive disinformation campaign, the months prior to the elections were filled with reports of AI-generated videos and audios. A fake video posted on YouTube alleged Lai had three mistresses, according to Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice. Another fake audio presented a presidential candidate mocking Lai for visiting the US on a “job interview.” One fake video portrayed incumbent President Tsai of the DPP encouraging Taiwanese citizens to buy cryptocurrency.

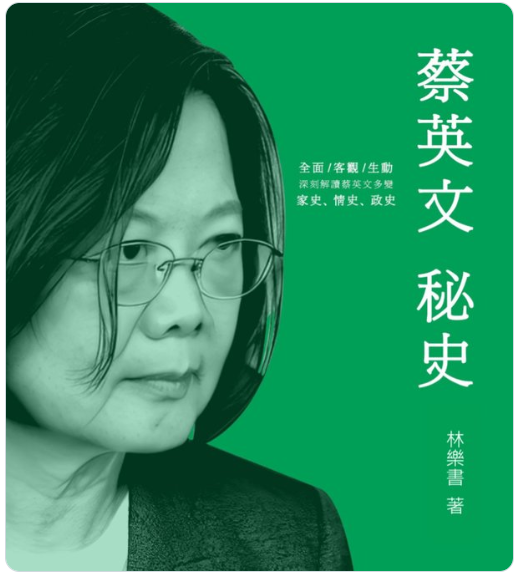

In the center of the misinformation campaign was a 300-page eBook titled “The Secret History of Tsai Ing-wen”, which contains false allegations about the island nation’s incumbent president and was circulated on social media platforms and by email. Soon after its publication, dozens of videos on Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, featuring AI-generated avatars acting as newscasters, reported the content as straight news. The book had become “a script for generative AI videos.”

Rather than create the disinformation itself, China allegedly functioned as an amplifier, locating critical materials and using its tools and networks to increase the visibility of the negative content on social networks.

Pakistan

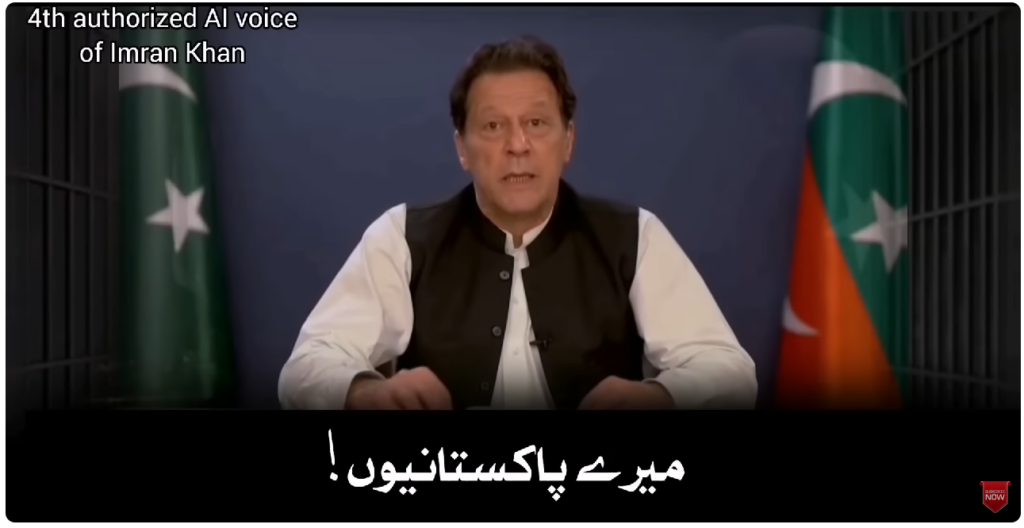

Pakistan’s 2024 elections, held on February 8 after a period of political turmoil and delays, were expected to favor former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif heading the Muslim League party (PML-N) backed by the military. Former PM Imran Khan of the PTI party was ousted from office in 2022, imprisoned and disqualified from running for office. Thousands of PTI’s members were jailed and almost all its senior leadership pressured to quit politics. With much of the party incarcerated for the duration of the campaign, Imran Khan’s party still managed to use AI to create and disseminate Khan’s message in support of independent candidates, creating speeches based on notes he passed to his lawyers from prison. These videos have an increased significance in a country with literacy rate of about 62%. Hours before the vote, a fake audio recording of Khan, calling on his followers to boycott the elections, was circulated in social media. But despite interferences by authorities, independent candidates backed by Khan’s PTI won 93 of 266 parliamentary seats. Regardless of the unpredicted success of the opposition, announced by Khan in an AI generated victory speech, the incoming coalition is expected to function as a “junior partner” to the military.

Indonesia

Indonesia presidential and parliamentary elections were held on February 14, 2024, and involved over 200 million eligible voters. Of the three main candidates, two of the campaigns made extensive use of AI tools to create “friendly images” and campaign materials in addition to official chatbots designed to conduct conversations with potential voters.

(source: channelnewsasisa).

However, AI was also used in many instances to produce videos and audios as disinformation. These included a video showing the current president, Joko Widodo, speaking Mandarin in an attempt to stir up anti-Chinese sentiments against his successor Prabowo Subianto, who had selected Jokowi’s eldest son as his running mate. Two fake videos presented candidates Prabowo and Anies speaking fluent Arabic, which neither of them speak. The intent was most likely to present them in a positive light as multilingual with strong Islamic ties.

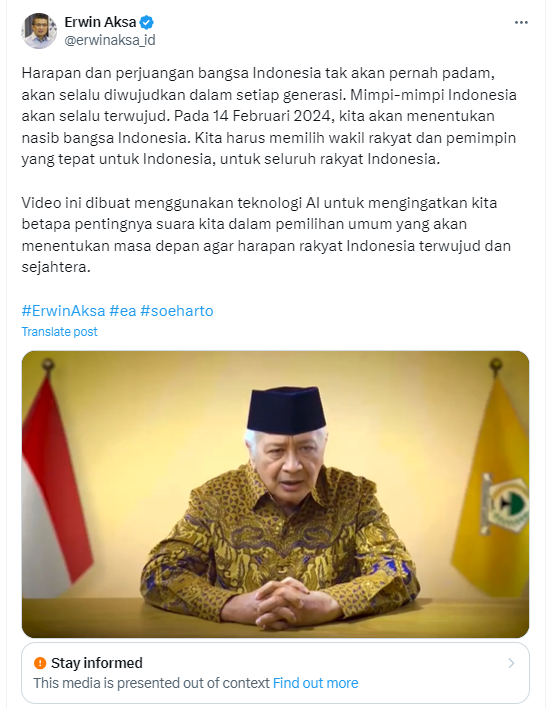

Candidate Anies Baswedan appeared in a fake audio recording, being scolded by his party chairman. In another case of fake “resurrection”, an AI-generated video showed the late president Suharto, who died in 2008, promoting Golkar, the party who endorsed Prabowo’s bid for the presidency. The video reached more than 4.7 million views on X and spread to TikTok, Facebook and YouTube after it was posted by the deputy chair of the Golkar party, Erwin Aksa, with a note stating it was made using AI. Indonesian laws currently prohibit defamation but not specifically the production and dissemination of fake materials.

United States

A fake robocall impersonating President Biden circulated in New Hampshire just ahead of the primary voting, urging Democrats not to vote and to save their vote for the November general elections. Following this event, The U.S. Federal Communications Commission outlawed robocalls generated by artificial intelligence.

UK

Despite not occurring under immediate election circumstances, two incidents involving AI-generated disinformation materials portraying political figures occurred in the UK.

More than 100 deepfake paid video advertisements impersonating Prime Minister Rishi Sunak were promoted on Facebook, according to research. The adds reached over 400,000 people and presented the PM as serving private business interests.

In another incident, London Mayor Sadiq Khan was involved in a serious situation due to a deepfake audio clip circulated online that featured him making inflammatory remarks before Armistice Day and endorsing pro-Palestinian demonstrations in November 2023. The AI-generated audio, which imitated Khan’s voice, disparaged Remembrance weekend and prioritized a pro-Palestinian march, leading to heightened tensions and clashes between protestors. The fake recording was shared on November 9, two days before the planned events, and spread rapidly, including among far-right groups, and triggered a spike in hateful comments against the mayor on social media.

London police say the fake audio “does not constitute a criminal offence.” Mr. Khan said the law is not “fit for [the] purpose” of tackling AI fakes, as the audio creator “got away with it.” He also expressed concern over the lack of legislation to address such deepfakes, especially during sensitive events like elections or community unrest.

Discussion

In our review of the 36 election periods, we saw that AI capabilities were utilized to create audio and video materials that reached public attention in at least a third of the cases. In some cases, the candidates employed AI to craft their own messages, or created negative materials focused on their competitors. In other instances, foreign entities used AI to create content that cast a negative light on certain candidates while generally sowing distrust.

Considering the plethora of tools and services available, and their actual utilization in campaigns in certain countries, the absence of AI evidence in other cases is very striking. Smaller electoral events, such as those in the Maldives and Madagascar, may go unnoticed in such analyses due to those countries’ size, language, or lack of international interest in their outcomes. However, no evidence of complaints regarding AI use were picked up by media outlets in elections in France, Canada (Manitoba), Germany (Bavaria and Hesse), Greece, New Zealand, Ecuador, and Finland. These countries rank relatively high in democracy indices (for instance, V-Dem 2023 v2x_api rankings of 11, 20, 16, 38, 7, 60, and 14, respectively). In nations where the public trusts independent media, the likelihood of spreading disinformation may be reduced. According to an article from the Harvard Misinformation Review, in such scenarios, the majority of people predominantly consume content from mainstream sources (as opposed to social media), and are therefore only marginally exposed to disinformation, no matter how convincing it may appear.

Disinformation campaigns have been identified as a fundamental tool in autocratic societies. Even in democracies, elevated levels of disinformation have been linked with the beginnings of autocratization. Consequently, it is plausible that the utilization of AI tools for disinformation would be more prevalent in autocratic nations, flawed democracies, and countries that are targets of autocratic regimes.

In many cases AI was used to generate materials traditionally produced by campaign staff or hired media consultants. This is apparent in examples from Argentina to Indonesia. A positive aspect of these tools is their use to bypass restrictions on free speech, as was done by providing a face and a voice to Pakistan’s imprisoned political leader Khan or a notable attempt to provide a voice to Belarus’s muted opposition. However, we must caution that tools designed to animate campaign ideas frequently results in misleading applications, such as putting words in the mouths of deceased leaders to endorse current politicians, a tactic that was employed in Indonesia and India or unverified emails in Poland.

Utilizing AI to “expose” the “real” views of opposing candidates often veers into the realm of disinformation. This was evident in Argentina, where the Massa campaign created a deepfake video of Milei “explaining” his vision for a human organ market, and in Poland, where the opposition animated the content of leaked emails.

When creating negative content about their opponents, politicians and campaigns frequently avoid distributing it through their official channels, instead using anonymous entities for dissemination. In some instances, such as the “iaxlapatria” Instagram profile in Argentina, these sources are easily identifiable. However, there are cases where political parties or politicians themselves echo these materials. There are numerous examples of political parties or prominent political figures posting or promoting disinformation, as observed in countries like Indonesia, India, and Slovakia. Targeting the distributors may prove to be a more feasible and effective approach in combating AI-generated fake materials than focusing on the original creators.

In some of the cases we examined, the creators clearly intended to convey misleading messages by fabricating content about their opponents. This strategy was observed in the Indian state of Telangana, as well as in Slovakia, Colombia, and Pakistan. The distribution of an AI-generated fabrication often occurs within a short timeframe before a crucial event such as an election. Mainstream media requires time to verify facts, and if such content is released shortly before an event or election, the authenticity might be disproved only after the damage has already been done. As we have seen, pre-election moratorium periods effectively silence mainstream media but do not impact the dissemination channels of fabricated content.

In the instances of fabricated “recordings” of opponents that we reviewed, the majority involved audio recordings instead of video. Despite the advent of advanced video tools, such as OpenAI’s text-to-video Sora which boasts the capability to generate high-quality videos from written prompts, the technology for audio manipulation is already mature and readily available for use. These audio technologies have been effectively utilized in most of the severe cases of election-related disinformation that we examined. In addition to their accessibility, audio recordings offer less context, making them more challenging to identify as fabricated, even with the use of advanced analytical methods.

In many countries, regulations have not yet been adapted to address the challenges posed by this new technology. In the UK, the police declared that the publication of a fabricated audio recording of the Mayor of London does not constitute a criminal offense. In Indonesia, fabricated materials that are positive in nature are legal, as existing regulations only prohibit negative defamation and not fabricated compliments. Given the experiences with AI exploitation cases, we anticipate that regulations will evolve. Look no further than the US, where, following incidents involving fake robocalls in New Hampshire, new regulations were promptly established.

The final category of AI utilization in the context of elections concerns foreign interference. The most notable case in the past six months occurred in Taiwan. The e-book mentioned earlier in this report was used as a starting point for subsequent deep-fake fabrications. Once the book was out there, others could seize on different elements which they then used to produce their own disinformation, resulting in a multifaceted common narrative.

Additionally, the significance of amplifying already available fake items has been underscored. The amplification is accomplished by directly influencing existing social platforms or by leveraging networks of pre-existing social entities that repost specific messages.

The playbook for foreign influence using AI is being written right before our eyes.

Conclusion

AI capabilities have been extensively utilized in recent elections, but the jury is still out on the degree to which voters are influenced and how much this affects the election results. Voters may be astute enough to see through the attempts to influence them; regardless, democracy does not rely solely on the notion that the public receives comprehensive, accurate and up to date information about affairs. Democracy does depend on public trust in its institutions and the electoral process. Institutions charged with upholding that public trust must continue to counteract disinformation. It is encouraging to note that, despite recent exploitations, fully developed democracies, where independent media benefits from the freedom of expression, have so far exhibited significant resilience to disinformation efforts.