Key Findings

- Check Point Research discovered a new set of malware called Veaty and Spearal that was used in attacks against different Iraqi entities including government networks.

- The malware samples described in this report use a variety of techniques including a passive IIS backdoor, DNS tunneling, and C2 communication via compromised email accounts.

- The passive IIS backdoor appears to be a newer variant of the backdoor reported by ESET as employed by the IIS Group 2 (also attributed by Symantec to GreenBug aka APT34).

- The malware has multiple ties to previously described APT34 malware families such as Karkoff, Saitama, and IIS Group 2 operating in the same region. Those malware families are affiliated with tun (MOIS).

Introduction

Check Point Research (CPR) has been closely monitoring a campaign targeting the Iraqi government over the past few months. This campaign features a custom toolset and infrastructure for specific targets and uses a combination of techniques commonly associated with Iranian threat actors operating in the region.

The toolset used in this targeted campaign employs unique Command and Control (C2) mechanisms, including a custom DNS tunneling protocol and a tailor-made email based C2 channel. The C2 channel uses compromised email accounts within the targeted organization, indicating that the threat actor successfully infiltrated the victim’s networks.

Using such distinctive C2 mechanisms, along with other attack-related artifacts such as malicious IIS modules, suggests possible connections to APT34, an Iranian MOIS-affiliated group. The malware families and methodology employed overlap with Karkoff, Saitama, and IIS Group2 clusters, all of which have ties to APT34.

Initial Infection

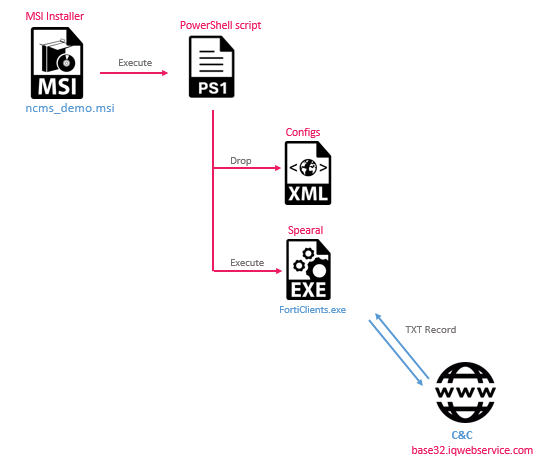

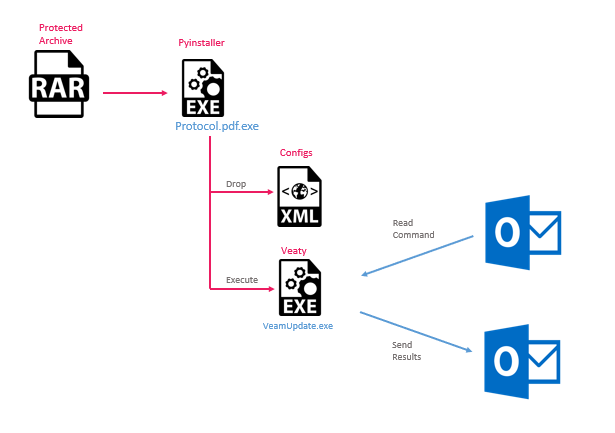

The initial infection for the newly discovered campaign is kicked off by a series of files that use double extensions to masquerade as document attachments. Examples of the file names include Avamer.pdf.exe, Protocol.pdf.exe, IraqiDoc.docx.rar. We also observed an infection that starts with an installer called ncms_demo.msi. All these files were uploaded to VirusTotal (VT) from Iraq in the months of March-May 2024. The initial infection likely started from some type of social engineering.

These files triggered the execution of PowerShell or Pyinstaller scripts which dropped two additional files: the malware executable (EXE) file and its corresponding configuration. Notably, the scripts manipulated file write and access times, and added entries to the Windows registry under \CurrentVersion\Run for persistence. An example of the Powershell script used to deploy the next stage:

$a1="TVqQA[truncated]"; $a2="PD94b[truncated]"; $ex_dir="c:\ProgramData\System Documents"; mkdir $ex_dir; $ex_path=$ex_dir+"\FortiClients.exe"; $con_path=$ex_dir+"\FortiClients.exe.config"; $ex_decoded=[System.Convert]::FromBase64String($a1); $conf_decoded=[System.Convert]::FromBase64String($a2);S [IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($ex_path,$ex_decoded) [IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($con_path,$conf_decoded) $ex_item=Get-Item $ex_path; $ex_item.LastAccessTime="05/08/2022 10:12:13"; $ex_item.LastWriteTime="05/08/2022 10:12:13"; $con_item=Get-Item $con_path; $con_item.LastAccessTime="05/08/2022 10:12:13"; $con_item.LastWriteTime="05/08/2022 10:12:13"; $dir_item=Get-Item $ex_dir; $dir_item.LastAccessTime="01/08/2022 06:11:47"; $dir_item.LastWriteTime="01/08/2022 06:11:47"; [System.Diagnostics.Process]::Start( $ex_path); New-ItemProperty -Path "HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run" -Name "Forti Startup" -Value $ex_path;

The next stage introduces one of two new malware families: Veaty or Spearal and their configurations. Both configuration files are structured as XML files with base64-encoded keys and values.

Spearal backdoor

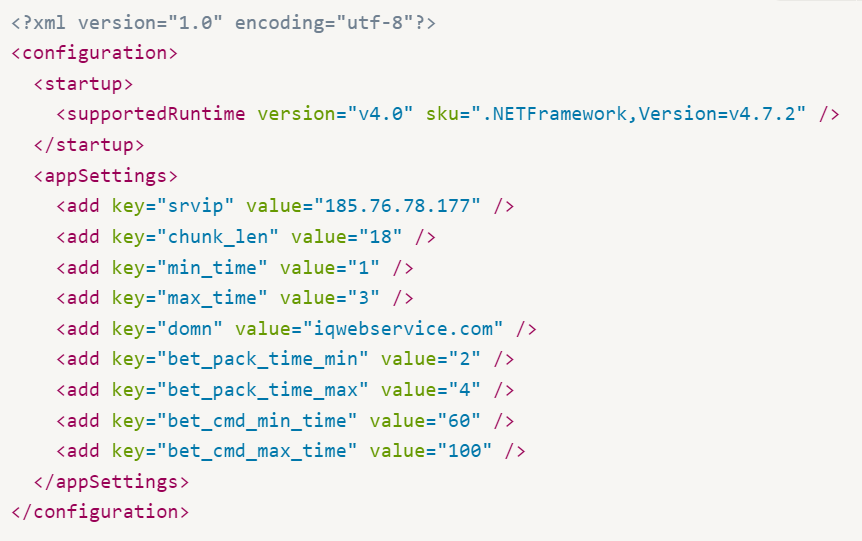

The Spearal malware is a .NET backdoor that utilizes DNS tunneling for communication. The Command and Control (C2) server is stored as srvip in the configuration file, and the malware sends TXT queries to this server.

The data transferred between the malware and the C2 server is encoded in the subdomains of DNS queries using a custom Base32 scheme. The domain used is either specified in the malware’s configuration domn field or defaults to iqwebservice[.]com.

The queries sent by the Spereal malware are detailed below, illustrating how data is transmitted to and from the C2 server.

- Initial Authentication:

- Query:

base32encode("auth:;<username>") - Response:

“stc:;base32encode(<target_comm_id>)”– This provides thetarget_comm_idwhich is the victim identifier used in subsequent messages.

- Query:

- Requesting Commands:

- Query:

base32encode("cmd:;<target_comm_id>") - Response: Contains one of these commands to execute.

- Query:

| CommandS | Description |

|---|---|

| cmd:;:; | Executes a PowerShell command. |

| dl:;:; | Reads a file and sends its base32-encoded data. |

| up:;:; | Retrieves content from the C2 to write to a file. |

- Sending Command Results:

- First Message (Command Result Start message):

- Query:

base32encode("crs:;<cmd_id>:;<num of chunks>")– The maximum length for a chunk is based on the valuechunk_lenin the configuration (the default value is 30). - Response:

“ok”.

- Query:

- Body Messages (Command Result Body message):

- Query:

base32encode("crb:;<cmd_id>:;<chunk_index>:;<chunk_value>"). - Response (Result OK message):

“rok:;<cmd_id>:;<chunk_index>”or“end”.

- Query:

- End Results (Command Result End message):

- Query:

base32encode("cre:;<cmd_id>").

- Query:

- First Message (Command Result Start message):

Veaty backdoor

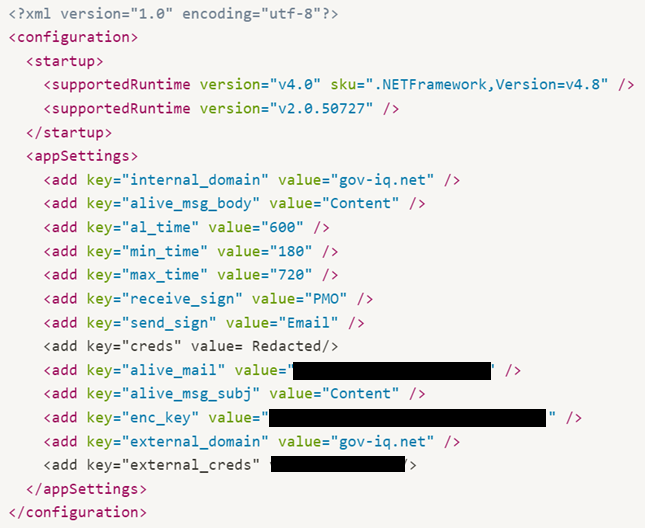

Veaty is a .NET backdoor that utilizes emails for C2 communications. It can upload and download files and execute commands. In the sample we analyzed, the malware leverages compromised email accounts at the gov-iq.net domain to execute its commands.

The infection begins with disabling certificate verification. This is the process that checks whether an SSL/TLS certificate is valid and trusted when establishing a secure connection to a server and allows the malware to communicate with the Exchange server (its C2) without being detected by certificate-based security measures.

The malware uses information from its configuration file in various aspects of communication with its C2 server:

Communication Channel Initialization

The malware determines which server to use and how to communicate with the server based on different hardcoded values. The malware has 4 flags (listed below) and attempts to communicate using each flag with a value of “True” until the communication with the exchange server succeeds.

The flags are used in the order in which they appear.

- try_defaultcred – Tries to communicate without username and password. The malware tries to communicate with each domain in the following order:

internal_domainfield from the configuration fileexternal_domainfield from the configuration file- the exchange server in the path on the compromised machine(

https:///EWS/exchange.asmx)

- try_hardcodedCreds – Uses the same list of servers, but the malware tries to communicate using credential values (username and password) from the “

creds” key in the config file. - try_externalCreds – Tries to communicate using values from the “

external_creds” key in the config file. The C2 server is based on a hardcoded value namedmail_domain_external_known,which in our sample is equal to “mail.miicrosoft.com”. - try_trustedNetwork – Tries to communicate using values from the “

trusted_networks_creds” key in the config file. The C2 server address is taken from a hardcoded value namedmail_domain_external_trustedwhich in our case is also equal to “mail.miicrosoft.com”.

Command and Control Communication

Veaty uses targeted mailboxes as its means of C2 communication. To prepare those mailboxes as C2 servers, it initializes a new rule so all its commands and responses will be moved to a relevant folder. Veaty has 3 values it uses to organize those emails:

communicationFolderreceive_signplaceForSignature– The value can be “subject”, “body” or “subjectorbody”.

The malware uses these values to search for a rule containing the receive_sign string in the placeForSignature field, with the target folder specified by the communicationFolder value. In this specific instance, it checks if there is a rule searching for emails with the string “PMO” in the subject field and moves them to the deletedItems folder.

If the rule doesn’t exist, the malware adds a new rule with this parameter. The rule’s name is taken from the inboxRuleName hardcoded field, which in our case is “MicosoftDefaultRules”. As a result, any email with the predefined string in the subject will be moved to the deletedItems folder. This setup helps the attackers use those mailboxes as C2 channels but reduces the chance of being discovered by the account holder.

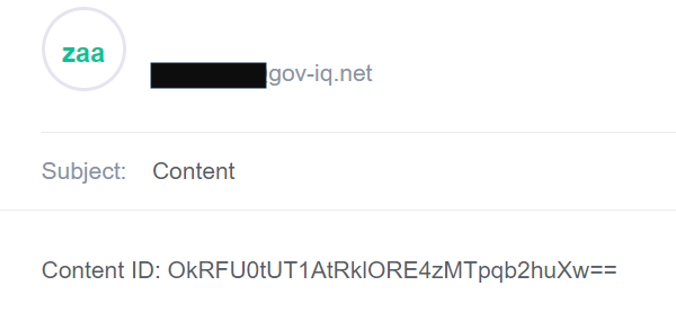

Veaty has two types of messages: Alive messages, otherwise referred to as “HeartBeat” messages, and Command messages.

Alive messages are dispatched as emails in the following format:

Subject: alive_msg_subj hardcoded value

Body: ”alive_msg_body” + “ID:” + base64(<ComputerName>:<UserDnsDomain>:<UserName>).

The recipient for Alive messages is based on the alive_mail value in the configuration file, and the message is sent at intervals (in minutes) corresponding to the value of al_time from the configuration file.

Command messages that match the rule established by the malware described above are searched for in the C2 mailbox. The command itself can be in the “attachment” (which was used in this specific campaign) or “body” of the mail, based on the hardcoded value ItemPlace. The commands are AES-encrypted with the enc_key value from the configuration file and base64-encoded. The commands are in the following format: <command_id>;<command>.

Command types:

- Download File – Commands that begin with the value “

this is my file content” hardcoded in the malware. The malware gets a file path and base64-encoded content to write to the file, with content segments separated by ‘’. - Upload File – Commands that begin with the value “

this is my required file path” hardcoded in the file. In this case, the malware gets a file path to read from and sends back its base64-encoded content to the C2. - Execute command – All other commands are executed directly using PowerShell.

The results are sent to the sender of the command mail and encrypted similarly. The format of the results email is also based on ItemPlace and the placeForSignature values:

| Hardcoded values | Subject | Body | Attachment |

|---|---|---|---|

ItemPlace = “attachment”, placeForSignature = “subject” | send_sign value from the configuration file (in our case “Email”). | “Hey There! find your results in the attachment” (hardcoded value). | Encrypted data with the filename “smile.txt” (hardcoded value). |

ItemPlace = “attachment”, placeForSignature = “body” | “Hey There! find your results in the attachment” (hardcoded value). | send_sign value from the configuration file (in our case “Email”). | Encrypted data with the filename “smile.txt” (hardcoded value). |

ItemPlace = “body”, placeForSignature = “subject” | send_sign value from the configuration file (in our case “Email”). | Encrypted data as the body of the email. | – |

The malware also contains several functions and variables it doesn’t use, which might indicate that it is based on different code and that the authors left in some extraneous data.

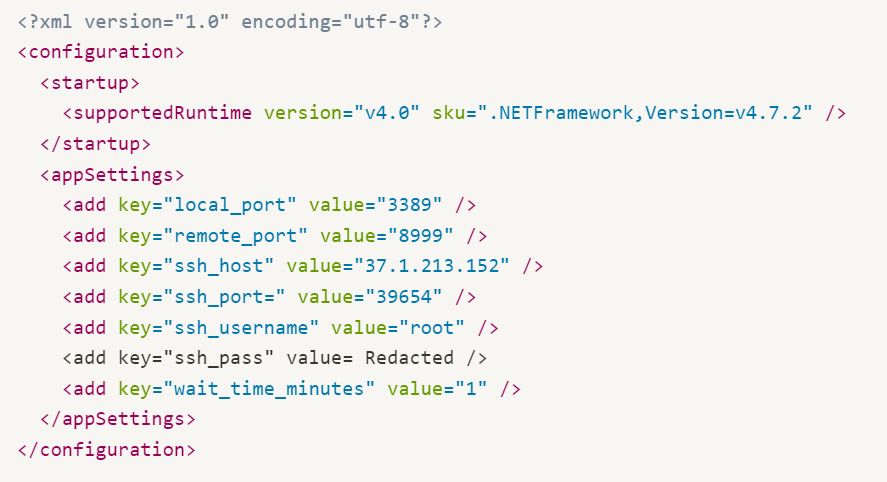

SSH malware

Analysis of the threat actors’ infrastructure led to the discovery of a similarly formed XML config file, likely used by a third backdoor to facilitate SSH tunneling. The IP address mentioned in the configs, 37.1.213[.]152, is associated with the domain mofaiq[.]com, pointing to the same targeting of Iraqi government entities.

Attribution

The Veaty and Spearal Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) are very similar to two other malware families, Karkoff and Saitama, which are attributed to the same APT34 actor.

TTP and Code overlaps:

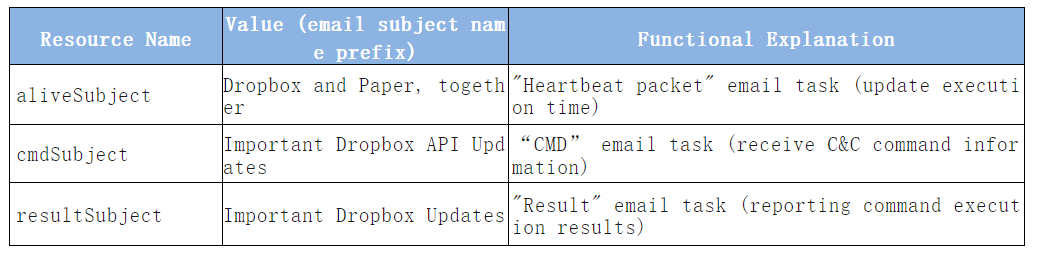

- Veaty malware uses techniques and variable names similar to those previously used by Karkoff malware. Both malware use email tunneling in the same way: searching for emails with a pre-configured subject (

Dropboxin Karkoff,PMOin Veaty), extracting from these emails commands to execute, and then deleting the email. The implementation of these methods is also similar.

- The Karkoff malware communicated through compromised email addresses belonging to Lebanese government entities, similar to Veaty, which used compromised mail accounts of Iraqi government entities.

- Spearal malware uses techniques that resemble the ones used by Saitama malware: they both use base32-encoded commands passed through DNS tunneling. Saitama was used in an attack that targeted Jordanian government entities.

asiacall.net, a C2 domain associated with this campaign, bears similarities to domain name conventions used by Saitama malware.

Using similar tools, techniques, and infrastructure against targets from the same geographical region leads us to conclude that this operation is carried out by an actor with a similar nexus to those who carried out previous Karkoff and Saitama attacks.

HTTP-Based backdoors

While investigating the previously mentioned samples, we encountered an intriguing IIS module backdoor named CacheHttp.dll that likely targeted the same organizations in Iraq. This module represents a newer iteration of malware that was previously attributed to IIS Group 2 and GreenBug.

The backdoor listens for OnGlobalPreBeginRequest events within the IIS server and executes its main functionality when these events occur.

The execution process begins by checking if the Cookie header is present in incoming HTTP requests and reads until the; sign. The main parameter is F=0/1 which indicates whether the backdoor initializes its command configuration (F=1) or runs the commands based on this configuration (F=0).

If F=1, the configuration parameters are included in the Cookie header after the , character as a series of key-value pairs in the following format: Cookie: F=1,a=[u/d/r/r2/r3]&b=[Shell_Command]&k=[Session_Key]&f=[File]

There are four keys:

a: Specifies the action (e.g.,u,d,r,r2,r3) discussed below.b: Encrypted shell command.k: Session Key encrypted with an RSA Private Key.f: Encrypted filename for download.

Supported commands:

| Command | Description | Parameters | Return Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| u | Write content to a file. | ‘f’ – filename, ‘b’ – data to write | The string ‘OK’ encrypted. |

| d | Read data from a file. | ‘f’ – filename | base64 encoded and encrypted data of the file. |

| r | Run command using popen. | ‘b’ = command | Encrypted result of the command. |

| r2 | Run command using CreateProcessW into a Pipe and read from it. | ‘b’ = command | Encrypted result of the command. |

| r3 | Create a pipe named "\\.\pipe\iis" and write/read data from there. | ‘b’ = command | Encrypted result of the data read from the pipe. |

The ‘b’ and ‘f’ values are encrypted with AES-CBC using the ‘k’ value and base64-encoded. The ‘k’ value is encrypted with an RSA private key that the attacker possesses, and the public key for this RSA private key is hardcoded inside the file.

The communication from the IIS backdoor to the C2 is encrypted in a similar way. A random AES-CBC key is generated and used to encrypt the data. The key itself is then encrypted with a public RSA key hardcoded in the file in which the attackers have the private key and then sent together with the data to the C2 server.

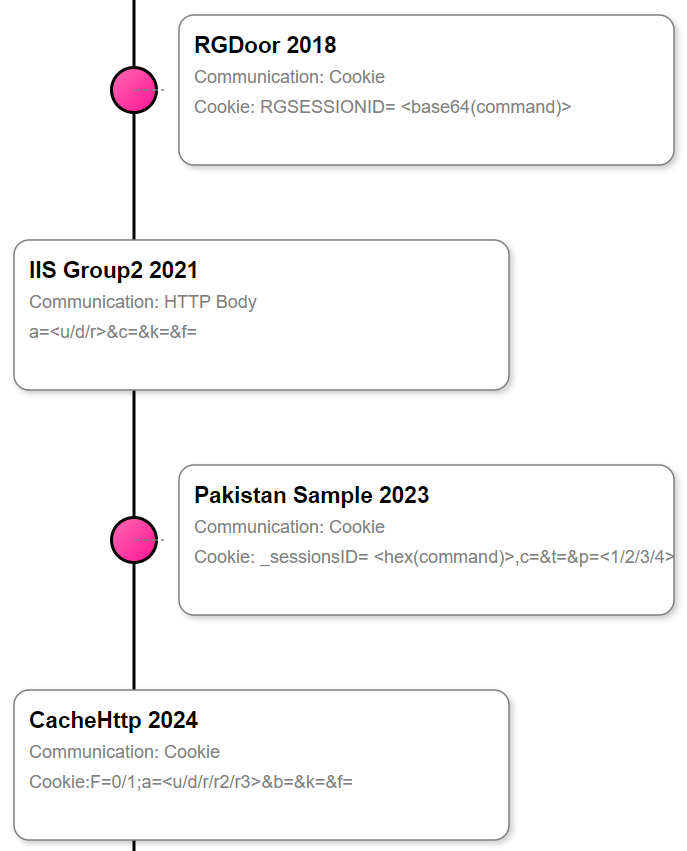

Evolution from IIS group2 and RGdoor

CacheHttp.dll represents an evolved version of the IIS Group2 backdoor. While its core functionality remains similar, it introduces two new additional methods for command execution: r2 and r3.

Notably, the communication flow has undergone a significant change. Unlike the Group2 variant, which communicates via the HTTP body, CacheHttp.dll now communicates through the Cookie field. This shift aligns with the communication technique observed in the older RGDoor, another IIS backdoor attributed to APT34. In RGDoor, the C2 communication format is:

Cookie: RGSESSIONID=<Encrypted command>

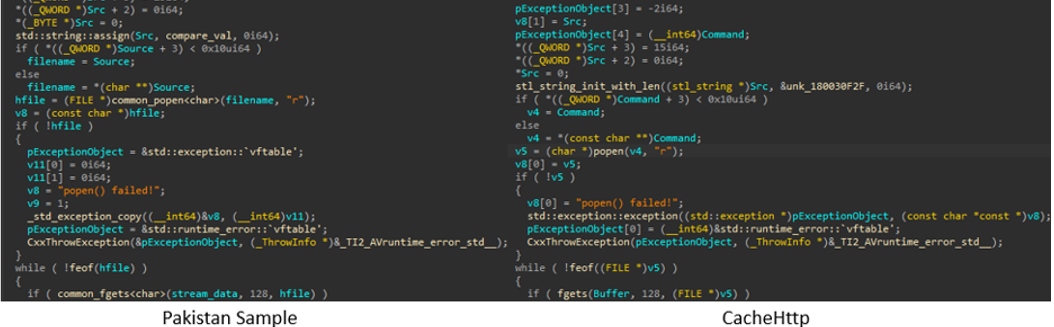

Another interesting sample, uploaded to VT from Pakistan in February 2023, represents a straightforward IIS backdoor with minimal functionality. Specifically, it offers four distinct methods to execute commands. Notably, this sample’s communication method shares similarities with CacheHttp. Commands are transmitted within the Cookie field in this format:

Cookie:_sessionsID=hex(value),c=?,t=?,p=[1/2/3/4]

The Pakistani sample utilizes four distinct methods for executing commands, suggesting a potential connection to CacheHttp, which employs three command execution methods (r, r2, r3). The code and implementation techniques show similarities between the two backdoors.

In addition, the close relationship between APT34 and Greenbug, and the overlapping TTPs and targets in the Middle East, suggests that all these tools, CacheHttp, IISGroup 2, and RGDoor, might be variants of the same tool.

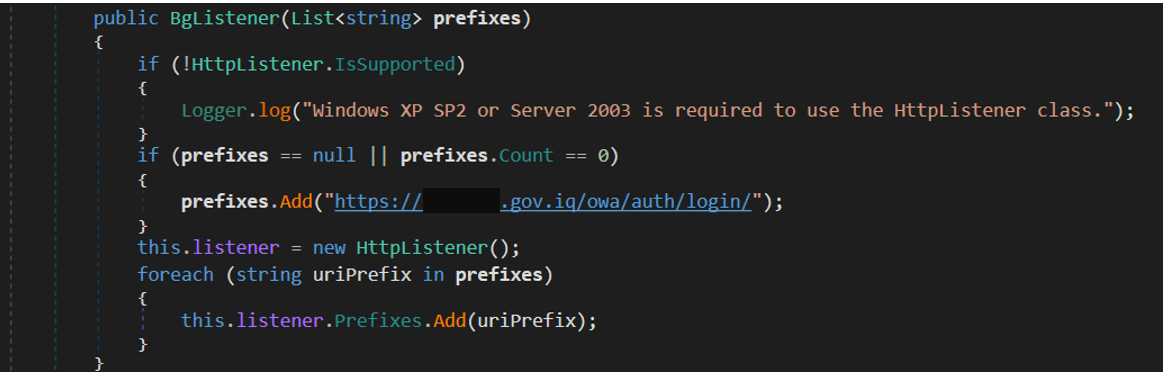

HTTP Listener – listner

listner is another passive backdoor uploaded to VT in the same context as the previously described malware. This tool is a basic .NET-based HTTP listener, registered to handle incoming HTTP requests to the URL https://[REDACTED].gov.iq/owa/auth/login. Incoming GET requests with the parameter snmflwkejrhgsey will execute its value via CMD, sending back the response in HTML format.

Despite its simplicity, this malware once again highlights the threat actor’s inclination towards passive backdoors.

Conclusion

This campaign against Iraqi government infrastructure highlights the sustained and focused efforts of Iranian threat actors operating in the region. The custom toolset and dedicated infrastructure observed in this operation are similar to techniques commonly associated with APT34, an Iranian MOIS-affiliated threat actor.

The deployment of a custom DNS tunneling protocol and an email-based C2 channel leveraging compromised accounts highlights the deliberate effort by Iranian actors to develop and maintain specialized Command and Control mechanisms. This distinctive blend of straightforward tools, written in .NET, combined with sophisticated C2 infrastructure, is common among similar Iranian threat actors.

The discovery of the Veaty and Spearal malware families and the presence of a passive IIS backdoor aligns this campaign with previously identified activity clusters like Karkoff, Saitama, and IISGroup2. These artifacts further solidify the link between this operation and APT34’s known tactics, techniques, and procedures.

Protections:

- Harmony Endpoint

- APT.Win.OilRig.F

- APT.Win.OilRig.WA.G

- APT.Win.OilRig.H

- Threat Emulation

- APT.Wins.Oilrig.ta.B/C/D/E

- AB

- Backdoor.WIN32.CacheHttp.A/B/C

- Backdoor.WIN32.Spearal.A/B/C/D/E/F

IOCs

185.76.78[.]177 91.132.95[.]117 151.236.17[.]231 37.1.213[.]152 206.206.123[.]176 194.68.32[.]114 iqwebservice[.]com mofaiq[.]com asiacall[.]net spacenet[.]fun Veaty and spearal: a79e4424116dc0a76a179507ac914578 1f1aaaf32be03ae7beb9d49f02de7669 b817309621e43004b9f32c96d52dc2a0 b5de3c4c582db7c2d2ce31c67cba0510 66126dc088be2699fd55ae7eff5e6e15 fb164cdf119b0d4427bdcb51b45075b1 7b62b055285b1c08e11ac98b3d3954bc 70ff5d4fc9957abff4c5577e22b3da27 4F4A06F63D34881D88CD70552E909748 85f025474271fbcc43af1e2203d10b66 2badde184d78ed901b4b2282b285717c Listner: d56b5fd6b8976c91d2537d155926afff CacheHttp: b1c93c7f5d89996d64a7f933f138e8b0 a70a7cfae52304a36fe1547b5a441d7a 79cc8730d748a884cc666b95ee9fed36 d542b320b10d443a454c305e9818f5f6 58e67cdc9ef57805f45ba554bdccb3b1 0f9d0b03254830714654c2ceb11a7f5d 8afdfd6d035b3c616dc37894a15206b4