Research by: Itay Cohen, Ben Herzog

Over the past two weeks, Ryuk, a targeted and well-planned Ransomware, has attacked various organizations worldwide. So far the campaign has targeted several enterprises, while encrypting hundreds of PC, storage and data centers in each infected company.

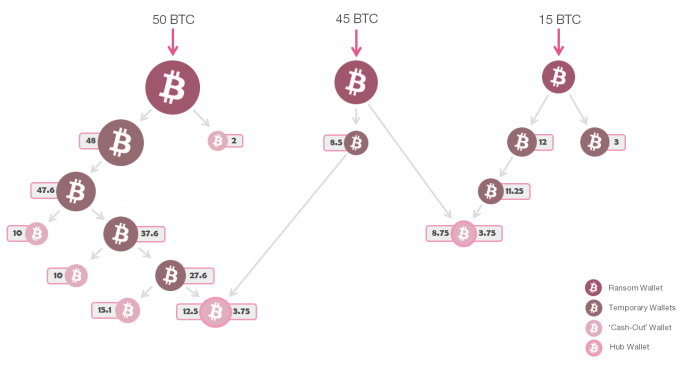

While the ransomware’s technical capabilities are relatively low, at least three organizations in the US and worldwide were severely hit by the malware. Furthermore, some organizations paid an exceptionally large ransom in order to retrieve their files. Although the ransom amount itself varies among the victims (ranging between 15 BTC to 50 BTC) it has already netted the attackers over $640,000.

Curiously, our research lead us to connect the nature of Ryuk’s campaign and some of its inner-workings to the HERMES ransomware, a malware commonly attributed to the notorious North Korean APT Lazarus Group, which was also used in massive targeted attacks. This leads us to believe that the current wave of targeted attacks using Ryuk may either be the work of the HERMES operators, the allegedly North Korean group, or the work of an actor who has obtained the HERMES source code.

In the below analysis we review the highly targeted attacks that Ryuk has been involved in and make a detailed comparison between it and the notorious HERMES ransomware used in other operations. We also address the financial aspects of the campaign and illustrate how, through tracking the money trail, Ryuk’s authors seem to want to disguise their received payments by dividing and transferring them among multiple wallets.

An Overview of Ryuk

Unlike the common ransomware, systematically distributed via massive spam campaigns and exploit kits, Ryuk is used exclusively for tailored attacks. In fact, its encryption scheme is intentionally built for small-scale operations, such that only crucial assets and resources are infected in each targeted network with its infection and distribution carried out manually by the attackers.

This, of course, means extensive network mapping, hacking and credential collection is required and takes place prior to each operation. Its alleged attribution to Lazarus Group, discussed later in this post, may imply that the attackers are already well experienced in the targeted attacks domain, as seen by attacks such as the breach of Sony Pictures in 2014.

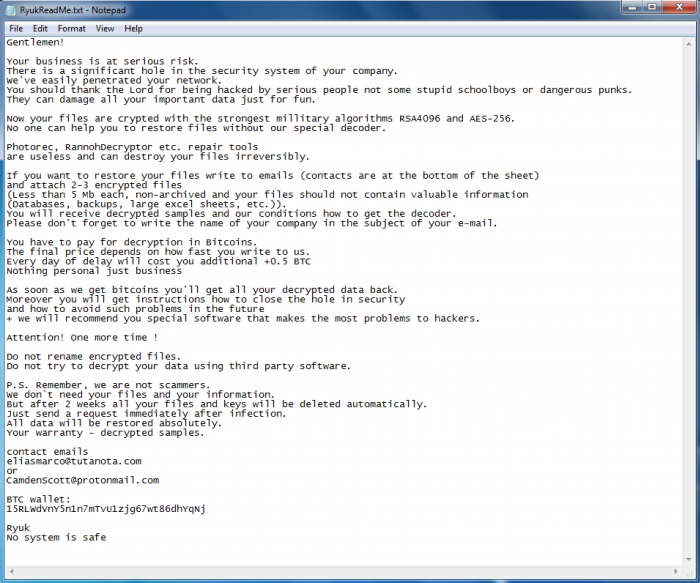

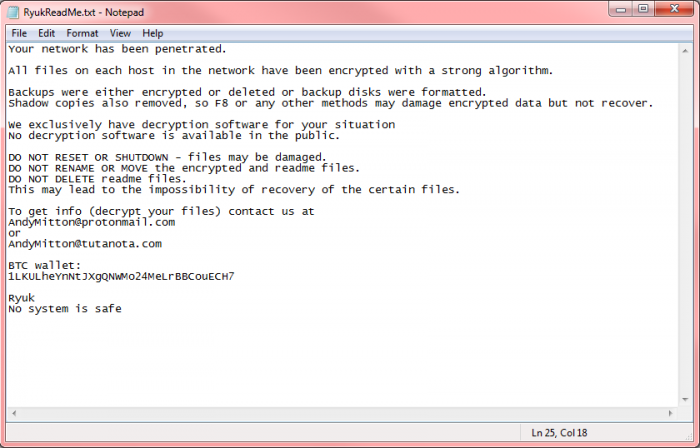

Ryuk’s Ransom Note

While no differences were found in the collected samples, two versions of ransom notes were sent to victims; a longer, well-worded and nicely phrased note, which led to the highest recorded payment of 50 BTC (around $320,000), and a shorter, more blunt note, which was sent to various other organizations and also led to some fine ransom payments ranging between 15-35 BTC (up to $224,000). This could imply there may be two levels of offensive.

Figure 1: Ransom Note #1; a pleasant, well-phrase note.

Figure 2: Ransom Note #2; a shorter, less detailed note.

Ryuk vs HERMES

The HERMES ransomware first gained publicity in October 2017 when it was used as part of the targeted attack against the Far Eastern International Bank (FEIB) in Taiwan. In that attack, commonly attributed to the Lazarus Group, a hefty $60 million was stolen in a sophisticated SWIFT attack, though was later retrieved. In this case, it seems the HERMES ransomware was delivered to the bank network as a diversion.

In the case of Ryuk, however, there is no doubt that the latest ransomware attacks seen over the past two weeks are by no means just a side-show but rather the main act. Indeed, with ransom payment as high as those already paid, Ryuk is definitely getting hitting the right note amongst its audience, or rather its victims.

The following technical comparison of Ryuk and HERMES leads us to believe that whoever wrote the malware was either in possession of the HERMES ransomware source code or is possibly even the same threat actor reusing code for yet another round of targeted attacks.

Malware Comparison

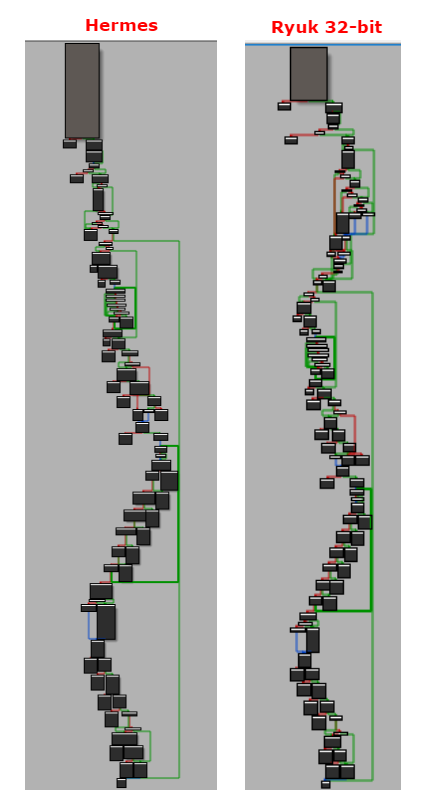

An interesting finding that arises when inspecting Ryuk’s code is that its encryption logic resembles that found in the HERMES ransomware, as outlined previously by Malwarebytes.

Indeed, if we compare the function that encrypts a single file, we see much similarity in its structure, as depicted in the following call flow graphs:

Figure 3: Call flow graphs of the encryption functions in Ryuk and Hermes.

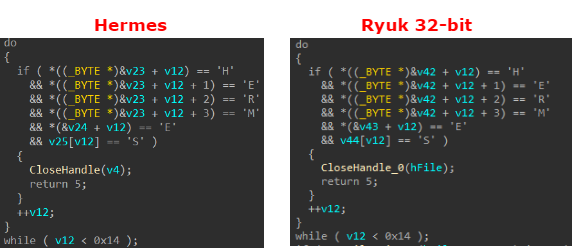

In fact, it seems that the author of Ryuk did not even bother to change the marker in the encrypted files as the code used to generate, place and verify this marker in order to determine if a file was already encrypted are identical in both malwares:

Figure 4: Marker generation in Ryuk and Hermes.

Figure 5: Marker check in Ryuk and Hermes.

Additionally, the function that invokes the aforementioned routine conducts very similar actions in both cases. For instance, both whitelist similar folders (e.g. “Ahnlab”, “Microsoft”, “$Recycle.Bin” etc.) to avoid file encryption of files stored in them. Also, both write a batch script named “window.bat” in the same path, with a similar script used to delete shadow volumes and backup files. Likewise, in both cases there are files dropped to disk (“PUBLIC” and “UNIQUE_ID_DO_NOT_REMOVE”) which resemble in name and purpose.

It should also be noted that all the above logic is preserved in both the 32 and 64 bit versions of Ryuk that we had samples of. Such similarity of code across different architectures might well be a sign of an underlying identical source code.

Technical Analysis

The Dropper

The dropper of Ryuk is simple and fairly straightforward. It contains 32 and 64 bit modules of the ransomware, embedded one after the other in the dropper’s binary. At the beginning of its execution, the dropper generates a 5-lettered random file name using the srand function and GetTickCount for seed generation.

The aforementioned payload files are then written to a directory, depending on the version of Windows on victim’s computer. If the version is Windows XP or Windows 2000, the file is created in the directory “\Documents and Settings\Default User\”, otherwise it is created in “\users\Public\”.

If the file creation fails, the dropper attempts to write it in its own directory, using its own name and appending the letter ‘V’ as the last character.

After creating the file, the dropper then checks whether the process is run under Wow64, and writes the suitable payload (32 or 64 bit) depending on the result of the check.

Finally, before terminating, the dropper calls ShellExecuteW to execute the Ryuk ransomware payload it has just written.

Ransomware Binary

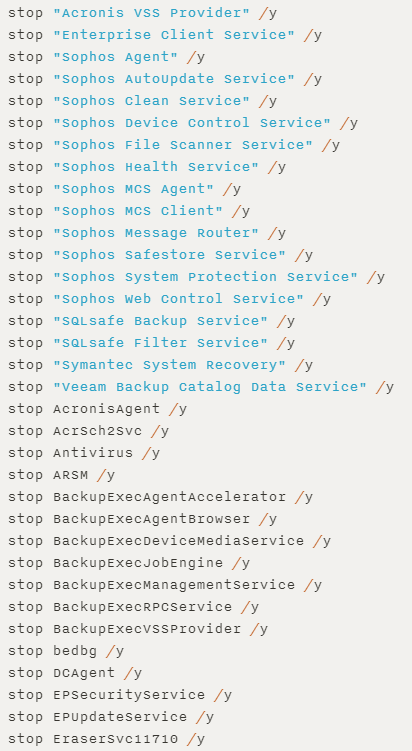

Upon execution, the Ryuk ransomware conducts a Sleep of several seconds and then checks whether it was executed with an argument. If such was passed, it will use it as a path to a file that is deleted using DeleteFileW. Based on the malware’s dropper code, this argument would be the path to the dropper itself. Following this, the ransomware will kill more than 40 processes and stop more than 180 services by executing taskkill and net stop on a list of predefined service and process names. These services and processes are mostly belonging to antivirus, database, backup and document editing software.

Figure 6: Partial list of killed processes and services.

Persistence & Process Enumeration

To make sure the malware is executed after reboot, Ryuk uses a straight forward persistence technique, whereby it writes itself to the Run registry key using the following command:

‘reg add /C REG ADD “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run” /v “svchos” /t REG_SZ /d’

It will then try to elevate to SeDebugPrivilege so as to have extended capabilities in subsequent actions and prepare for injection by forming an array of structures. Each entry in the array represents a running process in the system and contains the process’ name, PID, and a number which represents the account type of its owner (as outlined in the figure below). After putting the aforementioned process list together, Ryuk will iterate over it and try to inject a code to each process’s address space, as long as its name is not “explorer.exe”, “csrss.exe” or “lsaas.exe”, or is not run by NT AUTHORITY.

Figure 7: An array entry representing a running process in the system.

The Injection Method

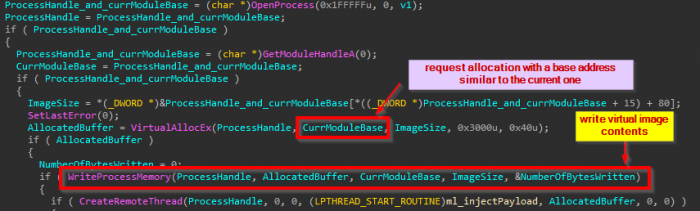

Ryuk uses a rather basic injection technique, whereby it first gets a handle on the target process using OpenProcess and allocates a buffer in its address space using VirtualAllocEx. The allocated buffer would have the size of the malware’s image and would be required to be positioned at the same base address.

The malware will then write its current virtual image content into it and create a thread that will carry out some actions, as described in the next section. Note that by writing the virtual image into a requested buffer with a predefined allocation base, and with the lack of a proper code relocation procedure, Ryuk is taking the risk that the requested address is not available for allocation, thus causing a potential failure in the execution of the injected code.

Figure 8: The injection method and bug that causes it to fail.

The Injected Code

The injected code holds the core functionality used by the ransomware for file encryption. It is started by decrypting a list of API function name strings using a predefined key and an array of the string lengths which is then used to dynamically load the corresponding functions.

In order to ease the decryption process during analysis, we created an IDA Python script that will automatically decrypt these strings and rename the relevant variables. The script can be found in the Appendix below.

Following this, the malware will attempt to write a dummy file to the Windows directory, which would only be allowed with Admin privileges. If the creation of the file failed, it will sleep for a while and attempt the same another five times. If failure persists beyond these attempts, Ryuk will simply terminate.

If the file was successfully created, it will write two more files to a subfolder in the Windows directory. The first is a file named “PUBLIC” which contains an RSA Public key, and the second is “UNIQUE_ID_DO_NOT_REMOVE” that contains a hardcoded key. Both are leveraged for the purpose of encryption as outlined in the following section.

The Encryption Scheme

The ransomware uses a relatively straightforward three-tier trust model. At the root of the trust model, as is typical in robust ransomware implementations, is the global RSA key pair held by the attackers. The private key from this key pair is not visible to the victim at any point during infection.

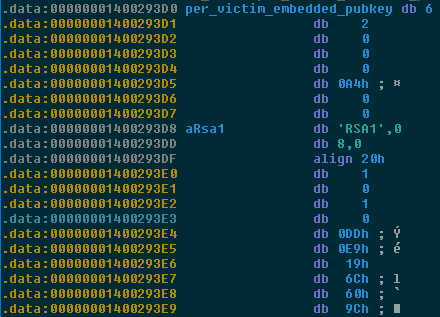

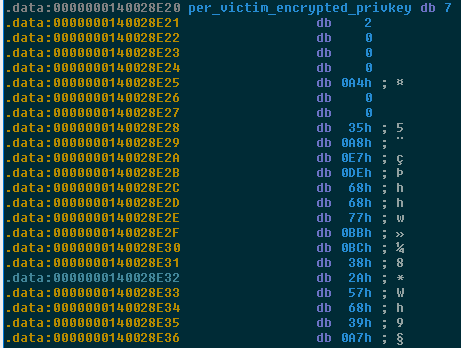

The second tier is a per-victim RSA keypair. Typically a ransomware would generate this keypair on-the-fly, and then immediately encrypt the resulting private key using the higher-tier global key. Instead, the ransomware comes with this keypair pre-embedded and the private key pre-encrypted. This is a somewhat unorthodox approach, which may be vulnerable to a ‘pay-once, decrypt-many’ attack if the same sample is used to infect multiple victims, or if the same keypair is embedded in multiple samples. But given that a fresh key pair is generated for each new sample, it is a secure model.

Figure 9: the embedded per-victim RSA public key (note the initial bytes 06 02).

Figure 10: The embedded per-victim RSA private key that has been encrypted

with the campaign global key (note the initial bytes 07 02).

The third tier is a standard AES symmetric encryption key generated per victim file using the Win32API function CryptGenKey. The key is then exported using CryptExportKey, encrypted using the second-tier key, and the encrypted result appended to the encrypted file. In a truly extraordinary turn of events, the authors actually read the documentation of CryptExportKey and provided the second-tier key as the hExpKey parameter, which is there exactly to provide this functionality. Most ransomware exports the AES key in plain and then encrypts the result using CryptEncrypt, or some such.

Figure 11: Assembly that generates the per-file AES key;

this is a part of the ransomware’s “encrypt file” routine.

Once all cryptographic primitives are in place, the ransomware performs a standard recursive sweep of every drive and network share on the victim system, and encrypts every file and directory except for any file or directory containing text from a hardcoded whitelist, which includes “Windows”, “Mozilla”, “Chrome”, “RecycleBin” and “Ahnlab”. It’s clear why the attackers would want the victim’s web browser intact given that it may be required for reading the ransom note, purchasing cryptocurrency and so on. But it is less clear why the attackers are concerned with encrypting the victim’s copy of a South Korean endpoint protection product, especially given that this attack wasn’t even targeted at South Korean users.

This bit in particular is one piece of a larger puzzle of how the HERMES ransomware came to be re-used and rebranded as “Ryuk” ransomware. Apart from the obvious re-labeling in the readme file and so on, there are subtle differences in the trust model.

According to a report by Malwarebytes, the original HERMES actually generated the tier-two per-victim RSA keypairs, as opposed to embedding hard-coded copies in the malware samples. But the encryption function itself, including the encrypted file format and its associated unique “HERMES” file magic, are reproduced wholesale in the rebranded version; as is the check for “AhnLab”-related files, which isn’t even relevant to Ryuk’s intended victims.

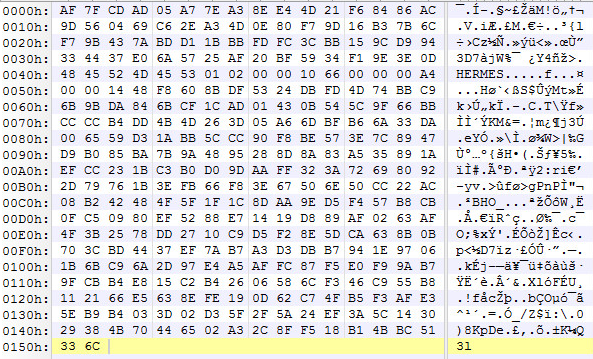

Figure 12: Hex dump of a file encrypted by Ryuk ransomware.

The file structure is visibly identical to the one used in HERMES,

down to the distinctive ‘HERMES’ marker, which the malware uses to identify files which it has already encrypted.

In addition to local drives, Ryuk will also try to encrypt network resources. First, it will start their enumeration by calling WNetOpenEnum, and then allocate a zero-initialized buffer. This buffer will be filled throughout a call to the WNetEnumResource function. If the enumerated resource is a container for other resources, the ransomware will call its network resources enumeration function recursively.

For each network resource found by Ryuk, the resource’s name will be appended and separated with a semicolon to a list that will later be used to encrypt these network resources.

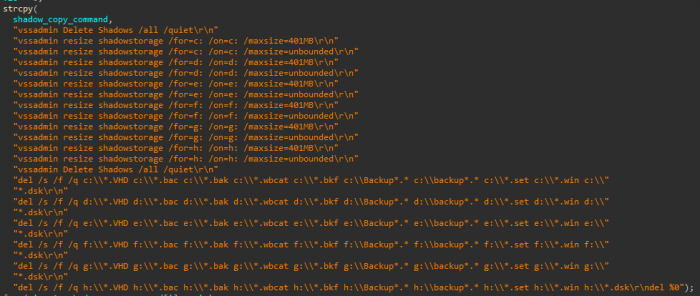

Finally, Ryuk will destroy its encryption key and execute a .BAT file that will delete shadow copies and various backup files from the disk.

Figure 13: List of Batch commands to be executed by Ryuk after encrypting the system.

Following the Money

Ryuk ransomware has not been widely distributed. Similarly to its forefather, HERMES, it has only been used in targeted attacks, which makes it a lot harder to track the malware author’s activities and revenues. Almost each malware sample was provided a unique wallet and shortly after the ransom payment was made, the funds were divided and transmitted through multiple other accounts.

However, examining the currency transactions directly from the wallet provided in the ransom note onwards exposed a pattern, which enabled us to pinpoint wallets that would most likely be used for monetization. We were also able to spot a connection between these wallets, as funds paid to them were transferred to several key wallets at a certain point. This may indicate that a coordinated operation, in which several companies have been carefully targeted, is currently taking place using the Ryuk ransomware.

After a ransom payment was made to a preassigned wallet, some 25% of the funds (a round amount such as 10 or 12.5 BTC) are transferred to a new wallet. These funds can still be found at that same new wallet that was created for them. We can assume that these wallets will later be cashed out. The remaining amount, indeed the majority of the original amount, is also transferred to a new wallet; however, the remaining funds are split and relocated again – some 25% of it is transferred to a new wallet in which it would remain, with the other funds split again, and so on.

Interestingly, several wallets were used more than others, as several transactions originating in different ransom payments were made to them. These key wallets were in fact the link between the original ransom payments, and enabled us to measure the extent of these coordinated targeted attacks delivering the Ryuk ransomware. The pattern we uncovered is presented in the chart below.

Figure 14: Bitcoin Transaction Flow, from the ransom payment to the cashing out stage.

Conclusions

From the exploitation phase through to the encryption process and up to the ransom demand itself, the carefully operated Ryuk campaign is targeting enterprises that are capable of paying a lot of money in order to get back on track.

Both the nature of the attack and the malware’s own inner workings tie Ryuk to the HERMES ransomware and arouse curiosity regarding the identity of the group behind it and its connection to the Lazarus Group. After succeeding with infecting and getting paid some $640,000, we believe that this is not the end of this campaign and that additional organizations are likely to fall victim to Ryuk.

Check Point’s SandBlast Agent Anti-Ransomware product protects against Ryuk ransomware. Here is a forensics report of Ryuk, triggered by SandBlast Agent Anti-Ransomware.

Appendix

String decryption Python code:

""" Ryuk strings decrypter

This is an IDA Python based script which can be used to decrypt the encrypted

API strings in recent Ryuk ransomware samples. After the decryption, the

script will rename the encrypted string in order to ease analysis.

Ryuk sha-256: 8d3f68b16f0710f858d8c1d2c699260e6f43161a5510abb0e7ba567bd72c965b

"""

__author__ = "Itay Cohen, aka @megabeets_"

__company__ = "Check Point Software Technologies Ltd"

import idc

from idaapi import *

def decryptStrings (verbose = True):

encrypted_strings_array = 0x1400280D0

lengths_array = 0x1400208B0

num_of_encrypted_strings = 68

key = 'bZIiQ'

if verbose:

print ("[!] Starting to decrypt the strings\n\n")

# Iterate over the encrypted strings array

for i in range(num_of_encrypted_strings):

# Get the length of the encrypted string

string_length = idc.Dword(lengths_array + i*4)

# Get the offset of the encrypted string

string_offset = encrypted_strings_array + i*50

# Read bytes from

# For IDA version < 7, use get_many_bytes()

encrypted_buffer = get_bytes(string_offset, string_length)

decrypted_string = ''

# Decrypt the bytes and save it to

for idx, val in enumerate(encrypted_buffer):

decrypted_string += chr( ord(val) ^ ord(key [idx % len(key)]))

# Set name for the string variable in IDA

idc.MakeName (string_offset, "dec_" + decrypted_string)

# Print to the ouput window

if verbose:

print("0x%x : %s" % (string_offset, decrypted_string,))

if verbose:

print ("\n[!] Done.")

# Execute the decryption function

decryptStrings()

IOCs

Ryuk Ransomware hashes (MD5):

c0202cf6aeab8437c638533d14563d35

d348f536e214a47655af387408b4fca5

958c594909933d4c82e93c22850194aa

86c314bc2dc37ba84f7364acd5108c2b

29340643ca2e6677c19e1d3bf351d654

cb0c1248d3899358a375888bb4e8f3fe

1354ac0d5be0c8d03f4e3aba78d2223e

Malware Dropper hashes (MD5):

5ac0f050f93f86e69026faea1fbb4450